|

June 1969 Electronics World

Table of Contents

Table of Contents

Wax nostalgic about and learn from the history of early electronics. See articles

from

Electronics World, published May 1959

- December 1971. All copyrights hereby acknowledged.

|

Light-emitting diodes (LED's) were still relatively new to the

scene of solid state electronics in 1969 when this article was published in

Electronics World Magazine. Two engineers from RCA Electronic Components wrote

to describe the state of the art in LED physics and features. The pair's prediction

that the LED would become "a light source that can be used for indication and display

wherever tungsten-filament, incandescent lamps are used" did not yet have enough

insight into the devices to know that four decades would pass before their prediction

would be realized. LED's have made continual progress over time, but it has really

only been in the last decade and a half that significant advances have occurred

- brought on largely by the desire to replace the "evil" Edison incandescent. If

you want to follow up-to-the-minute news on LED's visit the

Semiconductor Today

website; I go there daily looking for headlines.

This edition of Electronics World ran a series of diode articles:

Hot Carrier

Diodes,

Variable-Capacitance Diodes,

Tunnel Diodes,

Microwave

Power Diodes,

A Survey of Silicon Junction Diodes, and

Light-Emitting

Diodes.

Light-Emitting Diodes

Mr. Myers (top) is an Applications Engineer with the responsibility

for evaluating, rating, and supplying technical information on RCA LED's and related

products. He has been an Applications Engineer with the company for 6 years.

Mr. O'Brien (bottom) has been an RCA Product Development Engineer

for seven years and has worked on a number of semiconductor programs, including

thermoelectric power generation and IC's. He is currently responsible for process

development and device design on commercial LED's.

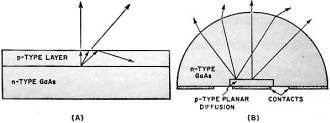

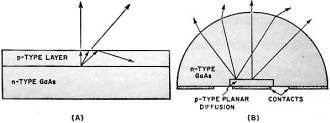

Fig. 1 - (A) Arrows show light produced in a flat-geometry

gallium-arsenide diode. At an incident angle greater than 15° there is a total

internal reflection and re-absorption. (B) Hemispheric-geometry LED overcomes this

limitation.

By R. S. Myers and J. O'Brien

RCA Electronic Components

These significant new solid-state devices can be used for indication and display,

replacing incandescent lamps in a good many applications.

The light-emitting diode, LED, a light source that can be used for indication

and display wherever tungsten-filament, incandescent lamps are used, is among the

most significant new semiconductor devices. Although it is still not fully developed,

it is clearly destined to become the of the most commonly used semiconductors in

military, industrial, and commercial electronics, as well as in consumer products,

such as electrical appliances and automobiles. The LED will, by its nature, be more

evident and have a greater direct effect on the consumer than the integrated circuit.

In short, the LED will be seen everywhere; a bold prediction based on its usefulness,

founded on the LED's inherent properties and advantages over other light sources.

The significance of the LED lies in the fact that it helps to fill a pressing

need for a simple, trouble-free means of displaying information obtained by electronic

equipment. At present, the output of such equipment is interpreted through pilot

lamps, neon-glow readout tubes, cathode-ray tubes, and mechanical printers. Some

of these devices cost more than the equipment with which they are used. The limitations

of these devices are overcome by the reliable, low-power, light-emitting diode.

The solid-state construction of this diode makes it a light source virtually

immune to catastrophic failure and mechanical breakdown. It eliminates the need

for sockets, special power circuits, and the additional operating tests necessary

to check tungsten-filament indicator lamps. LED's can be used as reliable fault

or warning indicators in power-supply monitors, blown-fuse indicators, logic-circuit

status indicators, battery-charge indicators, and failed-car-light indicators, to

name a few applications.

Beyond these simple "on-off" indicators are the display applications: alphanumeric

outputs from computers and memory systems, and various pattern readouts from such

diverse devices as watches, calculators, and measuring instruments. The use of LED's

in digital instruments has already been demonstrated by three firms. The future

growth of these displays will be accelerated by the simple IC driver circuits already

being designed.

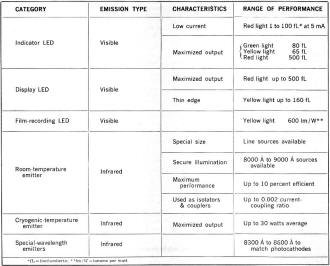

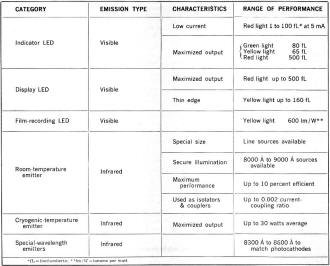

The LED's characteristics are best demonstrated by a comparison with a tungsten-filament

incandescent lamp (see Table 1). Table 2 shows the wide range of LED's that can

be manufactured within the present technology.

Fig. 2 - (A) Construction of LED using edge emission of

light. (B) Schematic of the RCA Type 40598A LED.

LED Operation

Some semiconductor materials can be made to emit light when excited in such a

manner that recombination of an electron and a hole results in the emission of a

photon. Although a p-n junction is not essential for electroluminescence, since

bulk materials have been made to emit light, it is still the most efficient means

of generating large numbers of holes and electrons and exciting them into the energy

levels needed for radiative recombination.

When a junction is forward-biased, electrons from the n region are injected into

the p region where they recombine with excess holes. In the radiative process, the

energy given up in a recombination is in the form of a photon whose wavelength corresponds

approximately to the band-gap energy of the semiconductor. The generated photon

then travels through the lattice until it is either re-absorbed by the crystal or

escapes from the surface as light.

The wavelength of the emitted light is a function of the band gap of the material

used for forming the junction. Pure gallium arsenide with a band gap of 1.4 electron

volts emits in the near infrared region, while visible wavelengths may be obtained

by using materials with larger band gaps, such as gallium phosphide (2.26 electron

volts), which produces green light. When gallium phosphide is doped with zinc and

oxygen, it produces red light and certain alloys of gallium arsenide emit reddish

light with the actual wavelength dependent on the composition of the alloy used.

The optical power output of a device is determined, in general, by the internal

geometry of the gallium-arsenide pellet and the type of package used. The simplest

type of geometry is the planar or flat-geometry device in which a shallow p-type

diffusion is made into an n-type substrate. Small-area contacts are applied to the

p surface of the device, on a standard TO-18 header; light is generated in the p-n

junction area and exits through the chip surface.

There are several limitations to the approach just described. As shown in Fig. 1A,

the very high index of refraction of gallium arsenide results in a very low critical

angle (15°) at the gallium-arsenide-air interface. Thus, any photons generated

within the crystal which arrive at the surface with an incident angle greater than

15° are subject to total internal reflection and are usually re-absorbed within

the crystal.

Table 1 - Comparative characteristics of light-emitting diodes

and conventional tungsten-filament lamps.

A structure which overcomes this limitation is shown in Fig. 1B. The gallium-arsenide

crystal has been ground and polished into a hemisphere and a planar p region diffused

into the base. By proper choice of crystal diameter, all light originating from

the region of the junction can be made to arrive at the surface of the hemisphere

with an angle of incidence less than the critical angle. Thus total internal reflection

is virtually eliminated. Devices fabricated by this technique exhibit efficiencies

about ten times greater than planar and flat-geometry devices.

Performance similar to, but less efficient than, that of the hemispheric crystal

can be obtained by covering a flat-emission chip with a dome of some material, such

as epoxy, that has a high index of refraction. An epoxy with an index of refraction

of about 1.5 improves the performance of uncoated devices by about 2 to 3 times.

Another method of utilizing the light generated within a crystal takes advantage

of edge emission, a mode in which light is emitted from the perimeter of the device,

as shown in Fig. 2A. The Type 40598A infrared emitter uses edge emission; in

this device light is emitted from the perimeter of a square-mesa-type diode that

is mounted in a parabolic reflecting surface, as shown in Fig. 2B. The emitting

area of the diode falls within the focal plane of the parabola. An epoxy lens forms

the optical window and aids in collimating the light to within 15° of the optical

axis.

In the past, high costs have hindered the development of a market for devices

like this. However, because costs have been steadily decreasing, the future appears

promising. The fifteen-dollar-per-gram cost of gallium-arsenide wafers is still

a problem, but refinements in crystal growth and better control of device fabrication

processes promise to lower costs even further as a volume market begins to open

up for light-emitting diodes.

LED Optical Systems

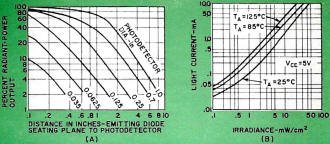

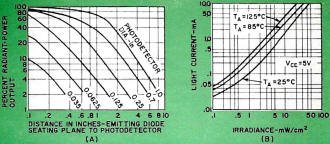

Fig. 3 - (A) Performance curve for 40598A LED having a nominal

output of 1.6 mW at 50 mA. (B) Performance curve for FPM-100 detector is used next

to obtain light current.

Fig. 4 - Block diagram of a pulse light system with LED.

The performance of an optical system incorporating an LED is difficult to describe

primarily because there are so many variables, including LED output, alignment of

LED and detector, beam spread of LED output, required detector output current, range

of radiation, and ambient light level.

In a given application, many performance factors are fixed. Manufacturers of

LED's and detectors provide data which makes it easy to predict the performance

of an optical system when these fixed values are known. The following paragraphs

describe several applications of LED's and show how their performance may be predicted.

For the purposes of this article, certain assumptions will be understood; namely,

that all of the output of an LED is at one wavelength, that the emitted beam of

light has uniform intensity, and that all parts of the system operate at nominal

values and ratings.

Optical System with Maximum. LED-to-Detector Coupling and No

Lens. An optical system of this type is referred to as an optical coupler. It is

used to provide voltage isolation and direct coupling of input and output; the isolation

may be several thousand volts. The method of predicting the performance of such

a system is as follows:

1. Look up total power received by the detector in data provided by the LED manufacturer.

2. Calculate power density on detector. Power density = [total power received

(mW) ] / [detector area (cm2)].

3. Obtain expected output from detector from data supplied by the detector manufacturer.

Correct data for wavelength of LED, if necessary, by using data supplied for this

purpose by the manufacturer.

As an example of the use of this method in actual practice, consider the performance

of an optical coupler composed of an RCA 40598A LED and a Fairchild 0.06-inch-diameter

detector (Type FPM-100) separated by a distance of 0.1 inch. The steps to be followed

correspond to those outlined above in the general-method description and are as

follows:

1. Total power received by the detector from the manufacturer's data given in

Fig. 3A is 28% X 1.6 mW = 0.45 mW.

2. Power density = 0.45 mW / π (0.03 in)2 = 159 mW/in2

or 25 mW/cm2.

3. Detector output current from manufacturer's data in Fig. 3B is about

4 milliamperes at 5 volts unadjusted for wavelength, and, applying a correction

recommended by the detector manufacturer, approximately 12 milliamperes at 5 volts

adjusted for wavelength.

Table 2 - This listing shows the wide range of light-emitting

diodes that are now being manufactured.

Optical System with Separated LED and Detector and No Lens.

A system with a separation between emitter and detector and no lens is needed for

applications such as card readers, tape readers, object counters on production lines,

and for simple intrusion alarms. The procedure for predicting the performance of

this system is the same as for the optical coupler if a performance curve for the

LED is available. For the important applications of card and tape readers, the information

called for in steps 1 and 2 is available directly from the LED manufacturer.

For applications in which there is a large separation between the LED and the

detector, the detector output is very small. Such a system becomes unusable when

the ambient light produces more detector output than the LED. Intrusion alarms,

photoelectric controls for production lines, and long-range signaling systems are

plagued by ambient-light problems. Ambient light varies more than 100 million times

from the dark of a movie theater to a bright sunny day and its exact level is not

easily determined. Even indoors, the ambient-light level varies greatly because

of window light, reflections, and shadows. Systems using LED's can be made independent

of ambient light by taking advantage of the LED's high-speed pulse or high-frequency-modulation

capabilities.

Pulsed and Modulated Light Systems

Pulsed or modulated light systems use detectors which respond to the pulse rise

time or high-frequency modulation of the light emitted by an LED and ignore the

absolute light level of the device. Tungsten lamps cannot produce high-speed pulses

and therefore must be used with absolute-value detectors which require that the

light of the emitting lamp be much greater than the highest ambient light expected.

LED's can be used even if the ambient light is stronger than that emitted by the

LED, as the following example demonstrates.

The 1 milliwatt of absolute light produced by the 40598A LED is detectable, under

room-lighting conditions, at a maximum distance of 2 inches, by a detector with

an area of 1 square centimeter. However, the pulsed light produced by the same device

is detectable at 2 feet under room-lighting conditions even with a 10-watt tungsten

lamp focused on a 5-square-millimeter detector to simulate the maximum ambient lighting

conditions. A 1-microsecond pulse with a repetition rate of from 100 to 5000 Hz

and a pulse power output of 6-milliwatts peak is used. A block diagram of the pulsed

system is shown in Fig. 4. By comparison with the absolute method, the pulsed

method shows an improvement in excess of 10 to 1 in working separation and in excess

of 100 to 1 in sensitivity, and displays a far greater improvement in immunity to

ambient light.

Systems with Lens

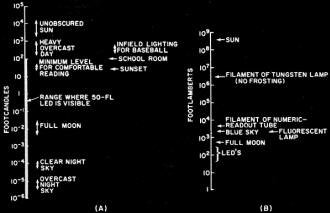

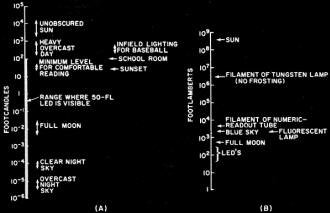

Fig. 5 - (A) Representative light intensities falling on

a surface along with (B) brightness of the various sources.

A lens placed between the LED and detector, but close to the LED, can be used

to direct uselessly diverging light toward the detector and thereby increase the

output of the system. Similarly, a lens placed between the LED and detector, but

close to the detector, focuses divergent light on the detector and effectively increases

detector size to that of the lens.

Because lenses greatly increase the output of a system, they allow greater LED-to-detector

separation; theoretically miles, and quite practically many yards. Clearly, the

use of a lens requires that the LED and detector be precisely positioned. Positioning

is often the factor which limits the effectiveness of an optical system and thereby

limits the separation of LED and detector.

LED's as Indicator Lights

The human eye responds to the difference in brightness (brightness ratio) between

the LED and the background. The total output and size of the LED are important in

that they affect the brightness of the LED; to be seen, an LED must be noticeably

brighter than its background. How much brighter depends upon the LED's color and

the brightness of the actual surroundings; i.e., the amount of ambient light, a

quantity that varies over a very wide range, as indicated in Fig. 5.

The range of illumination in which a 50-footlambert LED can be seen extends from

approximately 100 footcandles to total darkness. A tungsten lamp with a clear bulb

yields about 3 X 106 footlamberts and is therefore visible under higher ambient

light levels. Fig. 5 puts these ranges and levels in perspective.

The growth of the LED will be paced in the next three to five years by the development

of new semiconductor materials and the refinement of processing techniques. This

developmental sequence is completely analogous to the development problems and growth

cycle of other semiconductor devices which used new materials and therefore new

processing techniques. Perhaps the best analogy is the silicon transistor; however,

the silicon transistor is a great deal more complex than the LED.

At this time, comparatively few LED's are available. Technological problems and

high individual device costs related to unfinished engineering on these devices

are the most important limiting factors. However, present costs cannot be related

to costs five years or even one year from now. Both costs and performance will change

greatly for the better in the next few years as the technology advances. Future

products will include a large percentage of visible emitters, and larger, more powerful

devices that will be used in a greater number of larger, brighter, and more complex

displays.

|