|

March 1957 Radio & Television News

[Table

of Contents] [Table

of Contents]

Wax nostalgic about and learn from the history of early

electronics. See articles from

Radio & Television News, published 1919-1959. All copyrights hereby

acknowledged.

|

This 1957 Radio & Television

News magazine article purposes to set the record straight about the difference

between John A. Fleming's "thermionic valve

diode" rectifier, which did not produce signal amplification, and de Forest's

audion tube, which did provide amplification. U.S. patent number 841387, "Device for Amplifying

Feeble Electrical Currents," was issued to Lee de Forest on January 15, 1907,

a little over a year after Fleming received patent 803684 for his "Instrument for Converting

Alternating Electric Currents into Continuous Current" on November 7, 1905.

Unlike the contest between pro-Wright and pro-Whitehead camps who debate which party/parties

achieved the world's first manned flight which took off under its own power, the

record is very well documented regarding invention of the electronic amplifier.

Birth of the Electron Tube Amplifier

By F. B. Llewellyn By F. B. Llewellyn Bell Telephone Laboratories

Contribution made by de Forest is recounted for this 50th anniversary year of

his original patent.

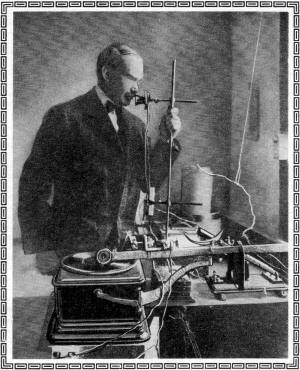

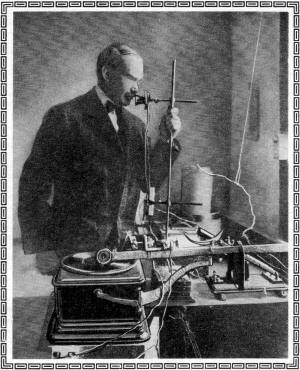

This picture of Lee de Forest broadcasting through an arc transmitter

was taken in 1907.

The early history of the electron-tube amplifier has been beset with confusion.

Much of this has been caused by failure to distinguish between the amplifier and

the detector. The whole situation with regard to Fleming clears up when this distinction

is kept in mind. The Fleming valve was instrumental in showing how the Edison effect

could be developed to produce a practical rectifying device. It never amplified,

though. It lacked the essential element, a third electrode, that would control the

flow of electrons without absorbing power in doing so.

de Forest supplied the first step, i.e., the addition of the third electrode.

However, even he did not develop its amplifying properties until a good many years

afterward.

The record of this three-electrode tube began on January 15, 1907, when the United

States Patent Office issued to him a very significant patent. Its number was 841,387.

It was entitled "Device for Amplifying Feeble Electrical Currents." This patent

describes an electron tube. The output current is controlled by an electrode that

does not itself draw appreciable current. This is the fundamental property of an

amplifier. The patent illustrates this use. It shows the control electrode in the

form of a plate located on the opposite side of the cathode from the anode. This

arrangement is capable of amplifying, but not as well as when the control electrode

is a grid located between the cathode and the anode.

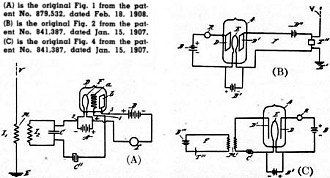

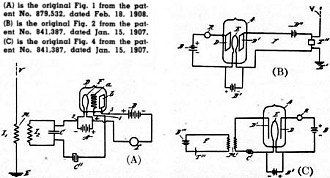

Another patent, de Forest's No. 879,532, issued a year later, shows the control

electrode in the form of a grid located between the cathode and the plate. (Fig. 1

of this patent.) This patent, however, describes the device only as a detector.

The original amplifier patent, however, describes the amplifying action and shows

two operable circuits. In one of them, Fig. 2 of the patent, the control electrode

has a positive bias. In the other, Fig. 4, there is an unbypassed blocking

capacitor in the external circuit of the control electrode. With gassy tubes, this

arrangement would work better than with the modern high-vacuum tubes.

Many patents had been issued before these two. Even more have been issued since.

It is fair to say, however, that few, if any, inventions have had as profound an

influence on the American way of life.

Modern society depends on quick and direct communication. This, in turn, demands

a "Device for Amplifying Feeble Electrical Currents." Such is the electron-tube

amplifier devised by de Forest. Today its uses are legion. It makes possible the

nation's long distance telephone system in its present form. Additionally, though,

it is essential in radio broadcasting, in television, in radar, in control of airplane

traffic, and in the large calculating machines and in guided missiles. These are

but general headings. The diversified uses of amplifiers in each category illustrate

anew the essential part that they play in the technology of· these fields. Today

the electronics industry measures its business in the billions, its personnel in

the hundreds of thousands.

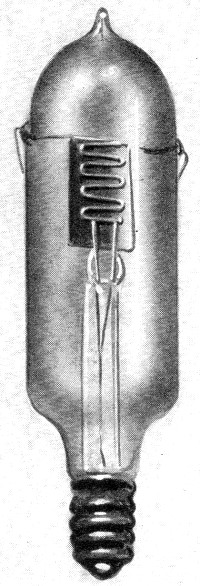

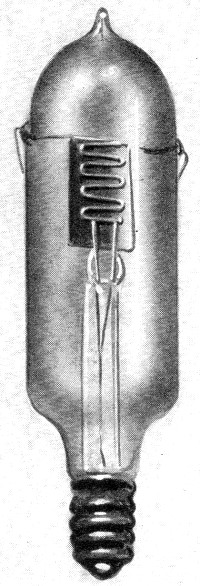

Photograph of the earliest type of three electrode Audion tube,

with the grid and plate leads brought out through the side walls of the cylindrical

glass envelope. Filament leads are connected to screw base.

January 15, 1957, marked the Golden Anniversary of this important patent issued

to Dr. de Forest. He has received honors before. However, in this 50th Anniversary

year of the electron-tube amplifier patent, it is especially fitting that we pay

our respects to its inventor. de Forest started a chain reaction that had profound

and far-reaching consequences. The first few links in the chain are especially worth

reexamining at this time. Also, some of the surrounding circumstances seem not to

have been made public before. In presenting this review, the object has been to

concentrate attention on the development of the electron-tube amplifier and its

circuits. By this approach, it is hoped that the story will emerge free from the

distractions that have involved it in the past.

New inventions of any technical complexity usually go through a period of growing

pains. The electron-tube amplifier was no exception. In fact, there was a period

of five long years after 1907 when almost nothing happened, One reason was that

attention had turned to another property inherent in the electron tube used in the

de Forest amplifier. This was its ability to detect modulated radio waves. Although

erratic, the early tubes formed more sensitive detectors for radio waves than anything

that had preceded them. We now know that much of this improvement was attributable

to their amplifying property. However, experimenters of 50 years ago did not know

this. Over 800 electron tubes, capable of amplifying, were made and sold* by W.

H. McCandless between 1907 and 1913. de Forest called them "audions." These tubes

were of the type in which the grid was located between the cathode and the plate.

Most of them were used by radio amateurs as detectors. A few, though, found their

way into the experimental laboratories.

There is little record, however, of any having been used as amplifiers until

1912. On January 27 of that year, Fritz Lowenstein demonstrated a vacuum-tube device

in a sealed box to F. B. Jewett and O. B. Blackwell, engineers of the Bell Telephone

System. The equipment did amplify but its action was erratic and uncertain. About

a year passed, with correspondence back and forth, before Lowenstein disclosed the

contents of a sealed box. This was probably the same sealed box that was demonstrated

earlier. At any rate, the box, on its second appearance, was found to hold one of

the de Forest audions of the type made and sold by McCandless. It was in a circuit

with the grid biased negatively with respect to the cathode of the tube.

In the meantime, Lee de Forest and John Stone Stone had demonstrated the amplifying

ability of the de Forest tube to the engineers of the Bell Telephone System. The

latter had had experience as a telephone engineer. He realized that an amplifier

for electric currents would be an important adjunct to the telephone system. It

would overcome the distance limitation on the transmission of conversations over

telephone lines. The demonstration took place on October 30 and 31, 1912. This time

there was no doubt about what the circuit contained. It was a de Forest audion with

the grid located between the cathode and anode. The circuit, however, was that of

Fig. 4 in the de Forest patent No. 841,387. As with the Lowenstein demonstration,

however, the amplifying action, although undoubtedly present, was erratic and unreliable.

Also, the absolute level of the output power was too low to be useful in telephone

circuits of that time. In those circuits, the amplifier was called upon to deliver

outputs that were much greater than would be needed to actuate a telephone receiver

directly. This was necessary in order that the currents could still produce sounds

audible above the noise in telephone receivers after having traveled a number of

miles down an attenuating telephone line.

The telephone engineers were greatly interested nonetheless. They organized a

project to study the circuit and tube and to determine whether its shortcomings

could be overcome. The engineer directly in charge of this work was Dr. H. D. Arnold.

He first saw the de Forest tube and circuit in operation on November 1, 1912.

One of the things he noticed immediately was that the de Forest tube developed

a blue haze whenever the plate voltage supply was raised sufficiently. This indicated

the presence of ionized gas. Moreover, Arnold calculated that the voltage would

have to be raised in order to get enough output power from the amplified voice currents

to operate in the telephone system. Thirdly, he concluded that ionization of the

gas present was not needed in order to make the tube amplify; in fact, that the

amount of amplification and the speech quality were better without it.

Early de Forest Audion. This picture came from

the late Sir Ambrose Fleming together with a label in his handwriting worded "de

Forest original valve or Audion. 1907." The over-all height of the tube, including

the screw base, is about 3 3/4 inches.

How to get increased speech output power without raising the plate voltage to

the point where ionization took place? In modern television language, this was the

$64,000 question. Actually, the answer that Arnold found has been worth many, many

times that amount.

Like many another great development, in retrospect the solution may seem simple.

As of the time, November 1, 1912, it was anything but simple. What Arnold proposed

was to pump the gas out of the tube. If there were no gas, obviously there could

be no ionization. What could be more obvious?

But wait - two very grave obstructions stood in the way: the one mental, the

other all too physical.

The mental obstruction stemmed from the fact that no one had supposed, before

Arnold, that audions would be capable of amplifying at all without the presence

of gas. Again and again we find evidence of this. The original patent of de Forest

calls for "an evacuated vessel inclosing a sensitive conducting gaseous medium maintained

in a condition of molecular activity." Arnold had heard of the attempts of a German

inventor, Robert von Lieben, to produce an amplifier tube. One of his structures

used magnetic deflection of an electron beam without appreciable gas. It did not

amplify, though. The deflecting coil absorbed too much power. Von Lieben then had

turned to experiments with a gas tube. An amplifier structure had been proposed

by Cooper Hewitt. This also required the presence of ionized gas. Too, the Bell

System engineers had been speculating about the kind of apparatus that was in the

closed box that Lowenstein had demonstrated almost a year earlier. The record shows

some freehand sketches of a tube driven by a control electrode external to the enclosed

portion. The shape of the glass structure was such that the presence of ionized

gas would have been essential to its operation. Then, too, current theories of how

electrons were emitted from hot cathodes required the presence of gas. Experiments

had shown that pumping the gas out of tubes reduced the current when the gas pressure

had become sufficiently low. Arnold wanted high currents, not low ones. To cap it

all, Arnold himself was developing a gaseous amplifier!

It was no small mental step to pass over this mass of opinion and experience

and say "Pump out the remaining gas."

Having said it, however, Arnold was face to face with the second obstruction:

the physical one. It was easier to say "Pump out the gas" than to do it. True, within

two weeks Arnold had succeeded in reducing the gas in one of the de Forest samples

by a substantial amount. He did this by heating the elements to provide a "getter"

action. After that, he took a more decisive step. He ordered a new, and better,

type of pump from Germany. By April 22, 1913, the new pump had arrived, been installed,

and was in good running order. By October 18, 1913, the resulting tubes had been

used to amplify telephone speech in repeaters installed in commercial circuits between

Baltimore and New York. In July, 1914, transcontinental conversations were going

through amplifying repeaters. They have been doing so ever since the official opening

to the public in January, 1915.

It would be difficult to find another momentous technical development that, once

started on the right track, moved with the speed and directness of this one. Less

than a year elapsed from the time Arnold first saw the de Forest audion with its

imperfect vacuum, on November 1. 1912. until the vacuum-tube amplifier had been

used on commercial telephone lines!

The high-vacuum concept and the development of high-vacuum tubes were not the

only contributions that Arnold made to the electron-tube amplifier. He also had

the foresight, or genius, to see that the grid blocking capacitor that de Forest

used was a hindrance. He got rid of it!

(A) is the original Fig. 1 from the patent No. 879,532,

dated Feb. 18, 1908. (B) is the original Fig. 2 from the patent No. 841,387,

dated Jan. 15, 1907. (C) is the original Fig. 4 from the patent No. 841,387,

dated Jan. 15, 1907.

Again, in retrospect, this seems to be a simple thing to do. However, at the

time it was not simple. Among all the conceivable things that might be causing the

de Forest circuit to balk and distort when large signals were applied, who but a

genius would realize within a matter of less than three weeks where the source of

trouble lay? On November 16, 1912, there appears a circuit diagram in the laboratory

notebook of Arnold's assistant, Mr. P. H. Pierce. It shows the blocking capacitor.

It also shows a strap drawn around it and the notation "short circuit." On November

26, 1912, Research Engineer E. H. Colpitts wrote to Assistant Chief Engineer F.

B. Jewett as follows:

"Two methods of using a valve having three elements, namely, a heated source

of electrons or a heated filament, a plate and a grid in an evacuated chamber, as,

for instance, in the audion, have been employed with the result that we have been

able to overcome the more serious defects in the behavior of the de Forest audion

used as apparently proposed by him ...

"In the sketch above, first method, a high resistance is bridged between the

plate and the grid, as shown. In the second method shown above the capacitor in

series with the grid is omitted. In addition to this it is also possible to introduce

an electromotive force in series in such a way as to largely prevent direct Current

from flowing in that circuit ... Of the two arrangements shown above, the second

one, with the capacitor in the grid circuit omitted, seems to be substantially more

efficient."

Thus was born the electron-tube amplifier. It took the genius of de Forest to

insert the third element, the grid, in the tube. It took his. genius to see that,

in this form, it could be used as a "Device for Amplifying Feeble Electrical Currents."

In addition, though, it took the genius of Arnold to grasp the situation, practically

at a glance, and come to an understanding of the causes of the limited output power

and erratic behavior of the gassy tube with its circuit containing an unbypassed

grid blocking capacitor that was demonstrated by de Forest and Stone Stone.

It is interesting to 'note that the two steps taken by Arnold were both in the

direction of getting rid of something that was causing trouble. We usually think

of a development as a putting-together. To improve a device, you add something to

it. In the vacuum-tube amplifier, Arnold did the opposite. He took something away:

first the gas and then the grid blocking capacitor. This is why his work had the

stature of genius. He had the boldness to take a course that was different from

the conventional; but he understood what he was doing and foresaw that it would

bring him to the desired goal. Through his keen scientific insight, the momentous

invention that de Forest had made was brought to a state where its inherent possibilities

could be utilized.

The whole episode illustrates, also, the fortuitous interplay of objectives and

situations that were present during the invention and development of the electron-tube

amplifier. In his earlier work, de Forest wanted a detector for radio waves. So

did most of the other workers with vacuum-tube devices. They thought in terms of

a modulated high-frequency incoming signal. They were trying to recover the envelope.

For this purpose, the severely non-linear properties of gassy tubes were desirable.

Their erratic behavior was to be put up with in order to obtain their advantages.

For an amplifier, on the other hand, the nonlinearity was a drawback. The gas offered

nothing useful. But it was hard to see this when one had been thinking of detectors

almost exclusively.

In the gas tubes of the day, the electrodes could be placed quite far apart.

In fact, many of the tubes worked better that way. Too, the glass bulb could have

protuberances to accommodate the electrodes. Consequently, the compact structure

of the de Forest "audion" was a step in a direction away from the conventional thinking.

And, finally, the part played by John Stone Stone should be remembered. He it

was who acted as catalyst. He brought together de Forest, who had a "Device for

Amplifying Feeble Electrical Currents," and the telephone engineers who had need

for an amplifier. Through this contact, Arnold was enabled to develop the device

into a reliable and flexible component. With it the development of the telephone

system into its present form was made possible.

*Records were made available by Mr. McCandless, first to Gerald F. J. Tyne, and

then by Mr. Tyne to the present writer.

These articles and advertisements involving Lee De Forest appeared in

various issues of vintage electronics magazines.

|

|

|

|

Posted June 21, 2021

(updated from original post on 5/22/2014)

|

By F. B. Llewellyn

By F. B. Llewellyn