|

June 1959 Radio-Electronics

[Table of Contents] [Table of Contents]

Wax nostalgic about and learn from the history of early electronics.

See articles from Radio-Electronics,

published 1930-1988. All copyrights hereby acknowledged.

|

The "Space Race" was in

full swing when this "Space Relay Station" article appeared in a 1959 issue of

Radio-Electronics magazine. The Russkies launched

Sputnik into Earth orbit on October 4, 1957. The U.S, to its shame, didn't

orbit a satellite until January 31 of the next year (Explorer 1). In

December 1958, Project SCORE marked the first successful demonstration of

space-based communications using an orbiting relay station aboard an Atlas

missile. This military-industry collaboration proved the feasibility of global

communication via satellite, transmitting both voice recordings and

multi-channel teletype signals. The 35-pound communications package operated in

three modes: storing messages on magnetic tape for delayed broadcast, instantly

relaying signals, or broadcasting pre-recorded messages. The project

demonstrated how space relays could overcome terrestrial propagation limits,

enable selective transmission timing, and potentially solve spectrum congestion

- heralding a new era in global communications technology that would eventually

evolve into modern satellite systems. This passage from the article suggests

that stable

geostationary orbits (~22,236 miles above MSL) had not yet been deemed

achievable: "When required, future satellites

can be controlled to hover as fixed radio relay stations. Four or five of these

at strategic locations in space will assure communications with any part of the

earth, no matter how remote or inaccessible."

Space Relay Station

A new era in electronic communications opens with this first

out-of-the-world rebroadcaster.

By Jordan McQuay

Successful orbiting late in December, 1958, of an Atlas missile-satellite carrying

a communications relay station was more than a step forward in space exploration

- it was the first advance in the science and techniques of global communication

via a relay station in outer space.

Not merely a quasi-propaganda stunt of broadcasting a taped message by the President,

it was a carefully planned and singularly successful experiment by military and

industry engineers and technicians. It marked the beginning of world-wide communications

using satellites in space as relay stations. For the first time, voice and teletypewriter

messages were accepted by a satellite in space, carried thousands of miles and,

on command, broadcast directly to ground stations. For the first time, signals from

earth were received by an orbiting relay station and re-broadcast over a greater

range than possible with conventional ground-based facilities. For the first time,

both the feasibility and importance of space relay communications were proven dramatically

and conclusively.

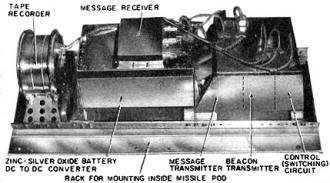

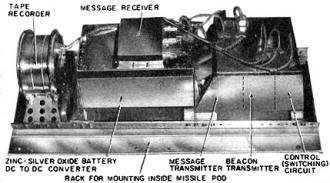

Fig. 1 - Communications relay station: project SCORE.

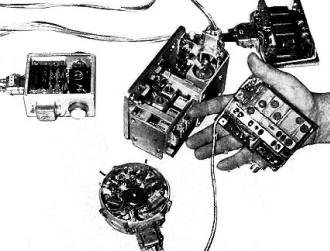

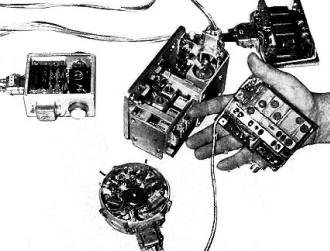

Fig. 2 - Electronic components of satellite: In hand, all-transistor

FM receiver. Behind it, control or switching circuit. Large unit (center), 8-watt

FM message transmitter. Left, power converter. Round unit (foreground), beacon transmitter.

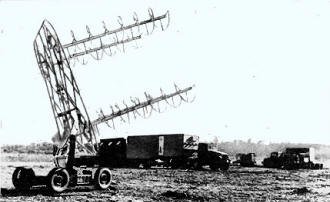

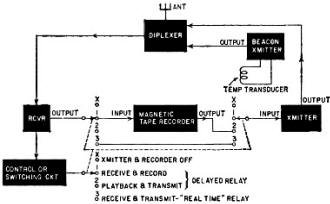

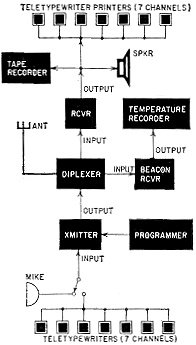

Fig. 3 - Block diagram of space relay station.

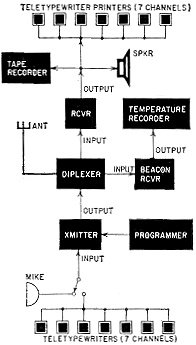

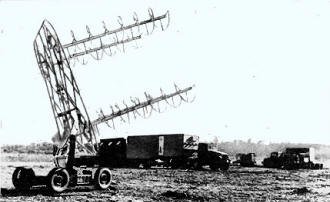

Fig. 4 - Typical ground station of the system. U.S. Army photo

Fig. 5 - Helix type antenna array of ground station. U.S. Army

photo

Though the gigantic size of the Atlas missile that became an earth satellite

was impressive, engineers and technicians were even more concerned with the scientific

significance and historic importance of the first space relay station.

Known as Project SCORE - Signal Communications by Orbiting Relay Equipment -

the space relay station was an Army- designed communications "package" (Fig. 1)

carried aboard an Air Force Atlas missile-satellite. During the 13-day life of Project

SCORE, a variety of technical tests - using both a voice signal and as many as seven

teletypewriter signals, singly and in groups - were conducted between the orbiting

space station and ground stations of the Army Signal Corps.

First in Space

The Atlas missile which placed the relay station in orbit was technically a 1½-stage

rocket. In addition to its single engine, it used ground-fired booster engines which

dropped off when the 4½-ton missile gained sufficient height and momentum. Equipped

with an elaborate internal guidance system, the Atlas followed a calculated path,

broke through the earth's lower atmosphere and went into orbit at a height varying

between 120 miles at perigee and 620 miles at apogee.

Once in its elliptical orbit, the missile-satellite traveled at about 17,000

miles an hour, making vast loops around the earth once every 100 minutes.

After a dozen orbits, the space relay station aboard the satellite was triggered

by an Army ground station and, for the first time in history, man's voice was broadcast

to earth from outer space. It was a brief message by the President, previously fed

to the relay station and stored for that broadcast.

Thereafter, the same message was transmitted from the ground to the orbiting

relay station, where it was either rebroadcast immediately or stored by a magnetic

tape recorder and rebroadcast later "on cue" from the ground.

Subsequently, single- and multi-channel teletypewriter signals replaced the voice

message. Using a bandwidth of 300 to 5,000 cycles, the space relay station continued

to operate as either a "real-time" relay or a delayed repeater.

All signals broadcast by the orbiting relay station were transmitted on a frequency

of 132 mc. The FM signals could be heard by anyone with suitable receiving equipment.

Control of the space station from the ground, however, was not a public matter.

This control-loading, switching and triggering - was limited to any of four ground

stations of the Signal Corps strategically located at sites in California, Arizona,

Texas and Georgia.

To prevent jamming or unauthorized use of the space relay station, the ground

stations used an unpublicized frequency for transmitting orders and messages to

it. In addition, a specially coded signal switched circuits within the relay station

to establish any of three modes of operation:

1. Receive signals from the ground, and record them on magnetic tape;

2. Broadcast previously stored signals to earth;

3. Receive signals from the ground and rebroadcast them immediately.

With various types and volumes of traffic, testing each of these three modes

of operation continued until the space station's only source of power - a battery

of zinc-silver oxide cells - was exhausted. By that time, all scheduled tests of

the entire system had been completed successfully.'

The Space Station

A complete space relay station is contained entirely within part of one of the

two pods or elongated "fins" on either side of the main body of the Atlas. The main

body, containing mostly fuel, is 10 feet in diameter and about 80 feet long. The

entire payload is divided between and enclosed within the two flanking pods or fins.

Most important part of this payload is the space relay station - a single "package"

about 25 x 9 x 10 inches (Fig. 1), weighing about 35 pounds. Controlled remotely

and equipped with its own power supply, it is electronically independent of other

parts of the Atlas. (See Fig. 3.)

The complete space relay station includes an FM message transmitter, an FM message

receiver, a control or switching circuit, a magnetic tape recorder, a beacon or

tracking transmitter, a dc-to-dc power converter and a zinc-silver oxide battery.

Communications components are shown in Fig. 2. The outputs of the two transmitters

and the input of the receiver are connected by a diplexer to a single slot type

antenna in the housing of the pod or "fin."

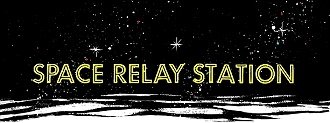

Fig. 6 - Block diagram of typical ground station associated with

space relay system.

The FM message transmitter operates nominally at a crystal-controlled frequency

of 132 mc. With a complement of nine tubes, the transmitter delivers 8 watts of

output power into an impedance of 50 ohms. Bandwidth limits are 300 to 5,000 cycles.

Required input operating power is 39 watts at dc voltages of -6, 135 and 270.

The FM message receiver operates at nominal frequency of 150 mc, in direct contact

with the transmitter of each ground station. Receiver sensitivity is 2 microvolts.

Its output level is 0.5 volt across 1,000 ohms - for a fully deviated signal. The

receiver is an all-transistor unit and requires only 25 mw of input power.

The control or switching circuit is essentially an arrangement of selective filters

that provide the three basic modes of operation. It is fully transistorized. When

activated by appropriate command signals from a ground station, it provides any

of four types of switching (Fig. 3).

The magnetic tape recorder is conventional, with a 4-minute storage capacity

for audio signals or analog data within bandwidth limitations. This storage capacity

can accommodate seven 60-word-per-minute teletypewriter channels, for a total of

about 1,680 telegraphic words.

A second transmitter - known as a beacon or tracking transmitter - transmits

a telemetered signal at a nominal OUTPUT XMITTER frequency of 108 mc and is crystal-controlled.

It has an output power of about 20 milliwatts into an impedance of 50 ohms. An all-transistor

unit, it requires an input operating power of 250 mw at dc voltages of -6 and 18.

The steady signal output of this transmitter permits tracking the satellite by Minitrack

and other ground monitoring stations - including amateurs with appropriate converters

for their receivers. The output signal is also telemetered with temperature data

from within the pod-enclosed space relay station. Temperature variations between

0° and 200 °C are recorded directly and broadcast by this transmitter independently

of other operations of the space station.

Primary power source for the station is a battery of zinc-silver oxide cells

which provides dc voltages of -6, -7.5, -12 and -18. Although these have a

limited operating capacity of about 950 watt/hours, they were selected because of

the anticipated short life of the missile-satellite and the relatively short duration

of the planned communications experiment. Supplying higher voltages, an all- transistor

dc-to-dc converter delivers 135 and 270 volts dc.

Fig. 7 - Control desk of ground station. Left: remote -control

equipment for orienting helix type antenna array. Right: FM message receivers.

RCA developed most of the communications equipment of the space relay station

in coordination with the US Army Signal Research and Development Laboratory at Fort

Monmouth, N. J.

Relay of Messages

The FM message receiver in the space relay station operates continuously. But

the FM message transmitter and the magnetic tape recorder are switched on and off,

as required, by the control or switching circuit. This circuit is actuated by a

special coded signal, transmitted to the satellite by any one of the four Army ground

stations.

Upon reception, this special signal causes a multiple switch to move to one of

four positions (Fig. 3) to select any of three modes of operation.

In position 1, the magnetic tape recorder is turned on and its input connected

directly to the FM message receiver's output. In this mode, signals received from

the ground are recorded and stored on magnetic tape. With a continuous capacity

of 4 minutes, the signals may be stored indefinitely for later use. Also, when directed

by a ground station, all or part of a previously recorded message may be wiped clean

from the tape in preparation for a new recording. After position 1, the control

circuit moves the switch to position X. In this position, the output of the FM message

receiver is disconnected from the recorder's input, and the recorder is turned off.

In position 2, the recorder's output is connected to the input of the FM message

transmitter, and the tape recorder and FM transmitter are turned on. Messages stored

on the magnetic tape are fed to and broadcast by the FM transmitter. After position

2, the switch moves to position X, which disconnects the tape recorder and the transmitter,

and turns off both.

In position 3, the FM message receiver output is connected directly to the input

of the FM message transmitter, and the transmitter is turned on for instantaneous

relay of all signals. All signals received from a ground station are rebroadcast

immediately by the FM message transmitter of the space station. After position 3,

the control circuit moves the switch to position X, which disconnects the transmitter;

but not the receiver, which operates continuously.

The sequence of positions 1 to X to 2 allows the space station to function as

a delayed repeater or "courier" of messages. Between positions 1 and 2, there is

usually a period of inactivity - a few minutes, a few hours or even longer. This

permits a high degree of selectivity of transmission by withholding signal transmissions

until the satellite is over or near the intended recipient.

In position 3, the space station functions as a "real-time" or instantaneous

repeater. This permits the station to rebroadcast signals over greater ranges than

possible for a ground station depending on conventional means of propagation of

radio waves. With a space station sufficiently high in the sky, line-of-sight transmission

is possible to most of the facing globe - nearly one-half the world. With several

stations strategically placed in space, it would be possible to broadcast signals

to the entire world.

The Ground Stations

Controlling the various operating modes of a space relay station and thereby

functioning as key elements of the complete communications system are the several

ground stations.

During the experimental tests, four mobile ground stations were operated by the

Army Signal Corps: at Prado Dam near Los Angeles, Calif.; at Fort Huachuca, Ariz.;

at Fort Sam Houston, Tex., and at Fort Stewart, Ga. All are similarly equipped.

Each ground station is housed in five trucks (Fig. 4) , which collectively contain

all communications, recording, control and power equipment. The antenna array is

a separate unit (Fig. 5). See the block diagram ( Fig. 6).

A single helix type antenna array is used for transmitting control signals and

messages, and for receiving messages and beacon or tracking signals from the orbiting

space station. Most of the other equipment, essentially conventional, is provided

largely by RCA and other industrial firms.

A 1- kilowatt transmitter is used for sending messages and control signals from

the ground station. Specially coded control signals are fed from a programmer. For

messages, either a voice signal or from one to seven teletypewriter signals are

used to modulate the FM transmitter. Multiplexing equipment can handle up to 60

words per minute, or a total of 420 wpm plus a voice or aural signal.

Messages broadcast by the space relay station are picked up on a highly sensitive

but conventional communications receiver, and fed to a magnetic tape recorder, an

aural reproducer or teletypewriter printers.

Beacon signals are received and recorded on facilities separate from the message-handling

equipment. Telemetered data - temperature readings - are plotted graphically.

All operations of a ground station are monitored from central control desk (Fig.

7). The control points at all ground stations are linked together by wire and radio

circuits to facilitate the rapid exchange of data.

Messages destined for an orbiting relay station can be fed to these ground stations

over commercial facilities from any place in the United States. Then, when the satellite

passes overhead or within range of a particular ground station, messages are transmitted

to the space relay station for either storage and subsequent controlled broadcast,

or immediate relay to other ground stations.

Info the Future

Tests concluded by the Army Signal Corps prove the complete feasibility of space

communications stations.

As delayed relays, future stations could provide highly selective transmissions

to specific geographical areas. For long-range or global communications, such "courier"

stations would require less operating power and fewer operating frequencies than

now necessary. With improved space communications systems, tremendous volumes of

messages can be stored, carried thousands of miles and released to ground receiving

stations anywhere on earth. All this with greater security of transmission than

is now possible.

As "real-time" relays, future stations could provide greater global coverage

from fewer broadcasting "points." More extensive use could be made of the existing

frequencies of the radio spectrum to provide world-wide communication during an

entire 24-hour period rather than for optimum periods of favorable propagation between

ground-based stations.

Thus, future space relay stations offer an important solution to the growing

traffic jam in the radio-frequency spectrum. Messages can be transmitted easily

on high frequencies that cannot be used for long-range or global communication between

ground-based stations. Eliminated will be "skip effects" and day-night propagation

problems of conventional long-range communication operations.

When required, future satellites can be controlled to hover as fixed radio relay

stations. Four or five of these at strategic locations in space will assure communications

with any part of the earth, no matter how remote or inaccessible.

Successful testing with a bandwidth of 300 to 5,000 cycles means that facsimile,

telemetry and other signals can be handled by future space relay stations. And many

messages multiplexed on a single operating frequency will also mean more available

channels for ground -based radio communications.

With improved space facilities, television signals can be similarly relayed to

any part of the globe by space relay stations. Such stations would require larger,

and more complex and powerful equipment, and would require solar power units and

appropriate converters for indefinite operation in outer space.

Future applications of space relay stations seem unlimited. And all of them loom

suddenly into the immediate range of present possibility as a direct result of the

Army Signal Corps' experiments with the world's first communications relay station

in outer space.

A whole new era is heralded by this practical application of satellites - a major

breakthrough in global and space communications!

1 - Because its great weight could not resist the slight but continual pull of

earth's gravity, the 4½-ton missile-satellite gradually lost altitude and speed

until, nearly 2 months later, it was consumed by frictional heat and disintegrated

in the atmosphere above the earth.

2 - "Tracking U.S. Satellites" by Jordan McQuay, Radio-Electronics, December,

1957

|