|

April 1961 Radio-Electronics

[Table of Contents] [Table of Contents]

Wax nostalgic about and learn from the history of early electronics.

See articles from Radio-Electronics,

published 1930-1988. All copyrights hereby acknowledged.

|

I don't know where the

name Mohammed Ulysses Fips (and neither do any of the AI engines I checked) came from, but it is the pseudonym chosen by editor

Hugo Gernsback. The first and middle names are easy enough to ascertain an

origin. According to the

iGENEA website: "The last name Fips is most commonly found in the

Netherlands, as well as in other parts of Europe. The surname originated in the

Netherlands, likely from personal names or nicknames related to the word "vips"

("expensive" or "luxurious"). The earliest recorded Fips dates back to 1490 in

the Netherlands." Hugo Gernsback was born in 1884 in

Luxembourg City (Luxembourg),

separated only by Belguim from the Netherlands, so maybe that is where he came

up with it. For some reason, the articles written by Mohammed Ulysses Fips,

purportedly a member of the Islamic Radio Engineers (I.R.E), always appeared in

April issues of Radio-Craft and Radio-Electronics magazine.

Here is his "30-Day LP Record" entry.

See the response from reader

Stephen A.

Kallis in the June issue.

30-Day LP Record

The completed 30-day record and player.

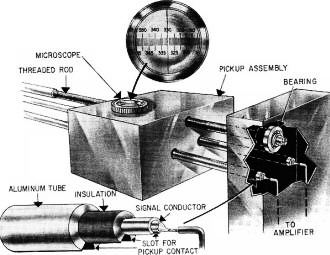

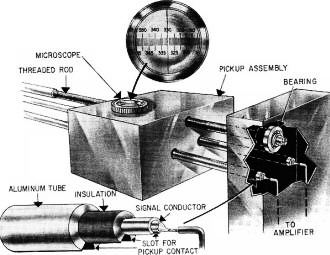

Detailed view of the pickup assembly.

By Mohammed Ulysses Fips, I.R.E.* By Mohammed Ulysses Fips, I.R.E.*

Remarkable new technique may foreshadow end of recording as we know it today

For the editor's birthday I had planned a big surprise - the world's longest

playing record!

When flat disc records made their appearance in 1894, they ran about 2 minutes.

Then came the long-playing (LP) record in 1948. This one ran about 30 minutes

per side.

Why stop there? For years I had wondered why no one made a really long-playing

record. I decided finally that what stopped most designers was the groove system

that somebody dreamed up, probably Edison for his first cylinder record. Later,

misguided designers blindly followed the groove idea and stuck in it. Why a groove

or channel in this day and age? Must there be a stylus in a groove to wear out the

channels in due time? Silly, isn't it? Why not just a fine threaded groove on a

spindle and let the reproducer ride in it? Then make the record of a magnetic compound

similar to today's magnetic tape - but make it ALL magnetic. Now the reproducer

no longer need touch the record at all - it floats 0.0015 inch above it.

The fine threaded spindle which carries the reproducer mechanism also has a reducing

gear to suit any required time elapse. This is, of course, nothing new. The same

idea is used in certain pocket watches that give the phases of the moon, and even

the year - it's all in the watch's reducing gear wheels.

The present-day standard LP record has a groove path about 3 1/2 inches wide.

There are about 900 parallel grooves, each about 0.001 inch wide. (Length of entire

groove path: 1,411 feet or 0.267 mile.) That's about as many physical grooves as

is possible to cut in the space available.

My new 30-Day LP Record is made of cast brass for rigidity, coated with a special

iron-nickel oxide compound on a base of hard plastics. For the all-important high-polished

smoothness of the record surface, which cannot vary more than 1/10,000 inch in thickness,

several special oxides have been added to the magnetic nickel-iron layer.

Naturally, the old-style pickup with its monstrously thick needle point that

travels in a groove cannot be used with a 30-day LP record.

Something far more sophisticated is needed for my modern magnetic pickup. And

here I had to go back to the old detector days of 1914.*

For the historic Electro Importing Co. (E. I. Co.) my boss designed the famed

Radioson electrolytic detector which, incidentally, was used by the United States

Navy for several years. It used an extraordinarily fine, exposed platinum wire point

0.0001 inch (one-ten-thousandth of an inch) thick. Wollaston wire is made of platinum,

coated thickly with silver. It is drawn down till the platinum wire is only 0.0001

thick. Then the silver is dissolved with nitric acid, leaving the almost invisible

platinum wire exposed. This was far too frail to be used in a portable commercial

detector.

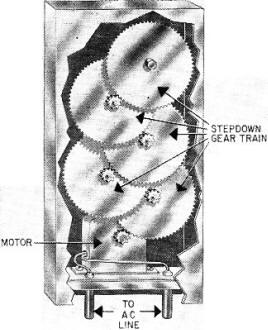

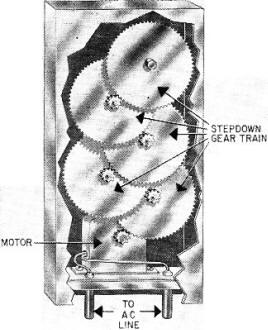

Reducing gears bring motor speed down to rotate the threaded

rod.

As there are no physical record grooves to contend with, we can

now make a recording of a fantastic number of phantom "grooves", in reality, paths.

Thus, instead of the mere 900 parallel physical grooves of the old LP record, we

actually have 1,152,000 magnetic paths covering 342.7 miles. (Theoretically, we

could have as many as 80,000,000 molecular- paths, a total of 23,780 miles. This

would give us an LP record running 69 months, or 5 years and 9 months!)

Here for the first time in print I disclose how the vital Radioson detector point

was manufactured.

A one-inch piece of Wollaston wire was held by its end in an alcohol burner flame

for a few seconds. That burned off the silver. Now the wire was inserted in a glass

tube and the fine, bare end of platinum was fused into the glass. When annealed,

the fused end of the glass tube was rubbed carefully over a fine-grain Carborundum

polishing stone, Under the microscope, the vital point was then inspected and repolished

till the face of a perfectly round platinum section could be seen in the microscope

field.

This was the heart of the Radioson. It was then fused into a larger glass tube

containing diluted sulphuric acid. The hermetically sealed arrangement made one

of the most sensitive radio detectors of the period.

I have chosen a very similar idea in my 30-day LP pickup (see illustrations).

Here, however, I use a magnetic pickup point. The "wire" in the sealed-off glass

tube is a variation of the recently discovered Whisker - a metallic crystal 1/20,000,000

inch thick. It is of nickel-iron coated with silver as in the regulation Wollaston

wire. The silver is removed, leaving only the nickel-iron core point that now becomes

the heart of the pickup.

The pickup travels only 0.0015 inch above the rotating record disc. The glass

tube that holds the nickel-iron wire has a special inductance winding surrounding

it, the ends of which are then connected to the amplifier. As the record revolves

below the pickup, the magnetic impulses go from the pickup wire to the high-fidelity

amplifier, exactly as in the old-time LP record, The pickup travels exceedingly

slowly across the record: it takes 30 days to traverse the distance of 3 1/2 inches

across the face of the record. The threaded spindle is turned at the proper speed

by a motor and reducing gears contained in one of the side supports.

But let us stay with my present 30-day LP record. Which brings me to the question

everyone asks: Why such a record at all?

Answer: Why have thousands of records when a few will do? Why clutter your house

with a large library of records when a few 30-day LP records will do?

My ambition - when I visualized my first 30-day record-was to construct a single

record disc, the same size as an old-style one, on which I could record ALL of Mozart's

works.

This sounds impossible if you consider all his operas, sonatas, songs, oratorios,

cantatas, concertos and symphonies - a total of over 600 works! Yet that is exactly

what I did.

I secured every Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart record I could buy or borrow and recorded

ALL of them on a single record. Unfortunately, not all of Mozart's works are recorded

on discs or tape - I fell far short of his 625 compositions. Over 50 had to be played

for me by a volunteer amateur orchestra to make the record as complete as humanly

possible. This took time - 8 months of actual recording!

Naturally you will ask who on earth will want to listen to a rendition of all

the hundreds of Mozart's works, continuously, day and night for 30 days!

Not so fast, friends. My 30-day LP record is something special, not intended

to be played uninterruptedly.

Running parallel to the spindle that carries the pickup and its gear works is

a micrometrically accurate scale numbered from 1 to 1,000. By lifting the pickup,

you can set its pointer on any number you wish.

The instruction card that lists all Mozart's works by key numbers tells you exactly

where to find each composition on the micrometric scale. Thus the complete opera

The Marriage of Figaro will be found on 189 of the scale. Set the pickup pointer

on 189, and you have the desired work. Don Giovanni will be found on 97, and so

forth.

The cost of such a record as it will be made commercially may run from $50 to

$80 - a very low price if you consider that a single record may replace several

hundred old-style LP's.

* * *

It was the editor's birthday when I presented him with the finished 30-Day LP

record. No one in the organization had had the slightest inkling of my epoch-making

invention.

The big boss seemed highly pleased, even fascinated, with it as I explained the

whole idea and its great possibilities to him. A lover of Mozart, he beamed his

pleasure as he selected the various compositions and played them at random.

But suddenly his face clouded. He bit off the end of his big cigar and threw

it down viciously. In an apoplectic rage he bellowed:

"Fips, you colossal nincompoop, you've done it again! If I ever print an account

of this insane contraption in our magazine, most of our advertisers will cancel

their contracts - we'll ruin them and they'll ruin us. Why don't you ever think

these things through, you ... you jabbering, jinxed jackass!"

With that he banged my head against something soft on the wall. As I fled out

of his office, I noted that he had slammed me against a thick, large leaf-type wall

calendar. The date read:

April 1

*Islamic Radio Engineers.

* See E. I. Co. Catalog No. 12. Also The Electrical Experimenter, January 1914,

page 144, and February 1914, page 146.

Posted April 1, 2024

These Mohammed Ulysses Fips articles appeared in Radio-Craft and later

in Radio-Electronics magazines, by in what I am sure is sheer coincidence

all appear in April issues (beginning in 1944)!

- Three-Dimensional Television - April 1965 Radio-Electronics (final appearance)

- Snorekill - April 1964 Radio-Electronics

- Teleyeglasses - April 1963 Radio-Electronics

- New - Electronic Razor - April 1962 Radio-Electronics

-

30-Day LP Record - April 1961 Radio-Electronics

- Paperthin Radio - April 1960 Radio-Electronics

- Ultra-Steered-Stereo Projector - April 1959 Radio-Electronics

- The

Transistom - April 1958 Radio-Electronics

- Lumistron - April 1957 Radio-Electronics

- The Cordless Radio Iron - April 1956 Radio-Electronics

- Silent Sound - April 1955 Radio-Electronics

- The Cosmic Generator - April 1954 Radio-Electronics

- No Article - April 1953 Radio-Electronics

- Noise Neutralizer - April 1952 Radio-Electronics

- The Hypnotron - April 1951 Radio-Electronics

- Electronic Brain Servicing - April 1950 Radio-Electronics

- Magnetic TV Enlarger - April 1949 Radio-Electronics

- Tubeless Homo-Heterodyne - April 1948 Radio-Craft

- New! Crystron Lapel

Radio - April 1947 Radio-Craft

- Now - A Radio Pen - April

1946 Radio-Craft

- Radium-Radio Receiver

- April 1944 Radio-Craft (first appearance)

|

By Mohammed Ulysses Fips, I.R.E.*

By Mohammed Ulysses Fips, I.R.E.*