|

December 1953 QST

Table of Contents Table of Contents

Wax nostalgic about and learn from the history of early electronics. See articles

from

QST, published December 1915 - present (visit ARRL

for info). All copyrights hereby acknowledged.

|

Designing, building, and tuning low

frequency filters is much easier for the person without a professional grade suite

of software, fabrication, and test equipment than is RF / microwave frequency filters.

Most of my design and integration work has been with system level transmit and receive

racks for radar and satellite earth station installations, and typically for prototyping

and/or very low quantity production. Accordingly, I often used connectorized components

cascaded together where each functional block was predefined and tested. I would

be handed a system input/output document that specified parameters for gain, phase

noise, intercept points, noise figure, group delay, bandwidth(s), power levels,

switching and settling times, current consumption, volume, weight, cost constraints,

etc. That explains why my software offerings like

RF & Electronics Symbols for Visio and

RF Cascade Workbook all deal with system level design. On occasion,

I needed to do some filtering at baseband, right in front of an A/D converter in

order to whack interference getting into the signal path from ambient sources that

ranged from non-compliant, unintentional RF radiators to noise spikes on power lines

cause by nearby equipment switching.

Filter Building Made Easy

Fig. 1 - Circuit diagram of the filter discussed in the

text. See Table I for sets of values for several cut-off frequencies in the audio

range.

Inexpensive Construction with Good Performance

By Charles L. Hansen,* W0ASO

The availability of ferrite-slug inductances offers the opportunity to make audio-frequency

filters of good performance. Here is a practical method of constructing low-pass

configurations such as might be used in low-level speech clippers.

The experimenter often needs a good low-pass filter that will pass frequencies

in the audio range up to a required cut-off point and provide 50 to 60 db. attenuation

beyond cut-off. Commercially-designed units for carrier telephone application can

be obtained, but usually cost thirty-five to one hundred and fifty dollars. Special

filters designed to cut off to the purchaser's specifications, as well as commercially

available filters, are priced beyond the reach of the average experimenter. The

compromise method of making a filter out of power-supply chokes is frequently taken,

but at the expense of performance in the final equipment. This is not very rewarding,

to say the least.

The purpose of this article is to describe a method of designing and building

a sharp cut-off low-pass filter with components that are available from any well-stocked

radio parts supply house. The passband and the sharp attenuation at the cut-off

point of this home-built filter are comparable with and in many cases equal to commercial

low-pass filters costing more than ten times the price of components used for this

filter.

Table I - Filter component values

A - Grayburne type V-25 variable coil, 5-43 mh.

B - Grayburne type V-6 variable coil, 0.65-6 mh.

Dimensions refer to length of slug inserted in coil as a preliminary setting

before tuning adjustments.

The capacitors should be good-quality paper units.

Most articles on "how to design filters" deal with the mathematical derivation

of the sections or meshes that make up the filter proper. After the filter has been

designed mathematically and diagrammed, many experimenters have been disappointed

in the actual performance of the completed filter. Because practical components

fall short of the ideal reactances on which the filter formulas are based, as well

as the difficulty of obtaining exact values, there is no substitute for practical

experimentation with any filter, and the final values of capacitance and inductance

may differ quite a bit from the calculated values. Also, most of us do not have

the equipment, time, or inclination to design, build and adjust filters from theoretical

information.

With the availability of recently developed variable ferrite slug-tuned inductors1

good filters are now within the budget of everyone. Not only do we have an inductance

that can be varied but we have the added advantage of a slug made of ferrite, which

increases the Q by reducing the resistance per unit inductance. These inductances

possess all of the qualities necessary for a good reactance which in turn results

in the building of a good practical filter.

A Practical Filter Design

The configuration chosen for the filter described here and shown in Fig. 1

provides for a minimum of inductances. The filter contains two shunt m-derived half

sections, one on each end, to provide a good impedance match from and to the flanking

circuit units. An m-derived full section and a constant-k section make up the other

two meshes. The m-derived section sharpens the cut-off characteristic and the constant-k

section assures that attenuation of the unwanted frequencies beyond the passband

will remain high. The impedance this filter must work into and out of is 500 to

600 ohms. Insertion of a filter into a circuit whose load impedance varies with

frequency will result in erratic operation.

Fig. 2

- Test set-ups for adjusting filters. If equipment having output and input impedances

matching the filter is available the simple arrangement shown above may be used;

otherwise the use of isolating pads as shown in the lower drawing is recommended.

Another alternative, when using an a.c. v.t.v.m., is to terminate the filter in

its characteristic impedance, and adjust the input voltage to a fixed value for

each frequency before making output measurements across the load resistance.

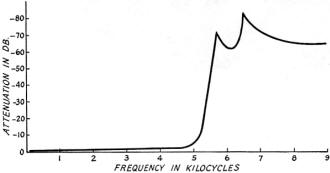

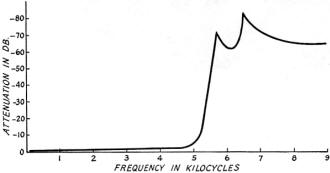

Fig. 3 - Measurements made by the author on a 5-kc. cut-off

filter constructed from the data in Table I.

Good practice in an extreme case of changing load impedances dictates the use

of T pads connected before and after the filter. The use of these pads reduces the

effects of source and load impedance variations with frequency.

Table I gives practical component values for several frequency ranges. For example,

if a low-pass filter having a cut-off of about 5000 cycles is needed, a set of values

will be found in the second row. Wire the condensers and inductances as shown in

Fig. 1 and adjust the ferrite slugs to the specified distances. Connect the

completed filter to an oscillator and a measuring set having 500- to 600-ohm impedance.

If an oscillator and measuring set with this impedance value are not available use

a pad set-up as shown in the lower drawing of Fig. 2.

Manually sweep the oscillator through the passband and check the uniformity of

response with the output meter or measuring set. Also check for the correct cut-off

frequency of 5000 cycles. Adjust the slugs on L2 and L3 alternately

to place the cut-off frequency at the desired frequency. Manually sweep through

the passband again and adjust the slugs on L1 and L4 for improvement

in the smoothness of the passband. These operations should be repeated until the

passband response is reasonably flat (within 0.2 db.). The frequencies beyond 5700

cycles should be attenuated 60 db. or more, with an attenuation peak of 70 db. or

so at 6500 cycles.

After adjustment the filter is ready for use. It may be enclosed in a metal box

taking up no more room than an average 20-watt output transformer. The individual

sections may be shielded from each other if desired.

Among the many applications that can be thought of for such filters are (1) speech

filters in communication work; and (2) audio use in recording and high-quality home

systems (see Audio Engineering for several discussions). For example, a 5000-cycle

filter can be used for sharply cutting off the hiss and scratch from old records.

1 The ones used by the author are made by the Grayburne Corp., 4-6 Radford

Place, Yonkers, N. Y.

Posted September 28, 2022

(updated from original post on 12/1/2016)

|