|

April 1939 QST

Table of Contents Table of Contents

Wax nostalgic about and learn from the history of early electronics. See articles

from

QST, published December 1915 - present (visit ARRL

for info). All copyrights hereby acknowledged.

|

Antenna radiation (beam) patterns published

by manufacturers are obtained under ideal - or close to ideal - conditions with

a carefully prepared and calibrated open air test site (OATS) or an enclosed anechoic

chamber. Multipath, imperfect earth ground, obstacles both manmade and natural,

misshapen elements, poor VSWR, antenna orientation (in both azimuth and elevation)

are among the many factors which produce real-world operational results that do

not jive with a manufacturer's datasheet. Without employing some far field 3-dimensional

field strength scheme (see

Drone-Based Field Measurement System™), there is no way to obtain

a complete picture of how your antenna performs in all directions. This article

presents a practical procedure for making measurements that will at least collect

useful data for specific orientations.

Checking Beam Antennas with the S-Meter

Converting Meter Beadings to Decibels for Signal-Strength Comparisons

By S. Gordon Taylor,* W2JCR

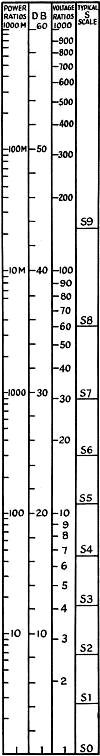

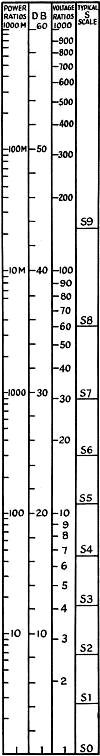

Fig. 2 - Voltage, power and db scales for quick conversion.

The S scale of the receiver in use may be plotted as shown in the right-hand column

so that reports can be given readily in terms of db gain or loss.

The "S" meters now so commonly employed in communications-type receivers are valuable

primarily as an aid in giving uniform signal strength reports, and in the constant

check on the operating condition of the receiver. But with the growing use of rotary

beams for transmitting and receiving such meter equipment is finding a new and important

application in checking the radiation characteristics, and even in plotting radiation

patterns.

Fig. 1 - S-meter calibrations of various receivers in terms

of decibels. The S scales are arbitrarily chosen by the manufacturers, hence the

wide variation in "db per S point." All values are relative to the lowest S-scale

reading on the receiver, and are independent of the receiver sensitivity. That is,

the fact that, in this chart, one receiver may show a reading of S7 while another

shows S4 for the same db value above does not mean that the signal input would be

the same in both cases.

Many hams recognize the possibilities in this latter application but fail to

take advantage of it because they (1) are unfamiliar with the procedure, (2) are

reluctant to undertake the calculations ordinarily involved, or (3) lack data from

receiver manufacturers which permits variations in S readings to be interpreted

in terms of decibels, power ratios or voltage ratios.

It is the purpose of this article to provide data on a number of standard receivers,

describe simple methods of checking characteristics and plotting patterns of rotary

beams, and provide a chart which reduces calculations to a matter of simple arithmetic

- with not an awful lot of that.

If you have a rotary beam and ask different stations for checks, the results

will normally be of only the most general value because for the most part these

reports will be given in terms of the number of S points difference between your

minimum and maximum signal. A three-S difference on one standard receiver may, in

terms of power ratios, equal a difference of five S's on another receiver, four

S's on a third, and so on. For this reason the S reports from different receivers

are not directly comparable, and it is impossible to arrive at any sort of average

suitable for use in plotting antenna characteristics.

Nor can this problem be solved by arbitrarily assuming some standard db value

per S point, a practice which is quite common. Measurements show that the "db per

S" may average anywhere from 3 to 6 on different standard receivers. This is another

way of saying that with one receiver model S9 may be around 50 db "up" from S1 while

in another model it may be only 25 db up. What is more, the db difference between

S3 and S4, for instance, may be quite different from that between S8 and S9 on the

same receiver and S meter.

What is needed is knowledge of the actual db calibration of the S meters for

the different receiver models, and this data will be found in Fig. 1 for nine

standard receivers. The data on which this chart is based was obtained from the

individual manufacturers, for this purpose (or from their literature in some cases),

and most of it appears in print here for the first time.

The utility of this chart is obvious. It serves to provide a useful calibration

for owners of any of these receivers. Of equal importance, it enables the ham to

interpret, in terms of db, the comparative reports received from others who are

using any of these receivers.

With rotary beams sprouting like mushrooms, the receiver S-meter takes on a new

importance in furnishing a means for giving information on radiation patterns -

provided its readings can be reduced to some standard. The important thing, of course,

is the relative signal strength, easily expressible in terms of decibels. Since

no two receiver S-point calibrations are alike, the information in this article

is particularly timely and useful, and gives the beam owner a means of correlating

signal reports.

Perhaps your receiver has a meter which you installed yourself and on which you

scaled off your version of the S scale. In that case you can obtain the decibel

calibration by comparing your readings on given signals with those of a friend who

owns one of the receivers of Fig. 1. This comparison must of course be made

with the two receivers in the same location and switching the same antenna. It will

be most simple if you calibrate your meter to correspond with the S scale of the

other; then its decibel calibration as given in Fig. 1 will apply to yours

also.

It is perhaps well to point out that the varying heights of the columns in Fig. 1

have nothing to do with the relative sensitivity of the different receivers. In

each case the column height simply represents the relative values which each receiver

manufacturer chooses to employ in designing and calibrating his S meter circuit,

and it is obvious that the different scales are not in agreement. The fact that

some calibrations start at S° and others at S1 is of no importance; this again

simply represents the manufacturer's choice of zero db level but does not in any

way alter the utility of the db data of this chart.

When the owner of a rotary beam receives reports on his front-to-back ratio in

terms of decibels these reports from different stations can be directly compared

with a far greater degree of accuracy than would be the case were the reports simply

given in S points. For example, suppose two receiving stations gave him reports.

One, equipped with a "Sky Challenger" receiver reports readings of S9 for the front

and S3 for the back. The other, using an "NC-100" reports S9 for the front and S6

for the back. On the basis of straight reports (without the data of Fig. 1)

it would appear that the signal variation as observed at the first station is twice

as great as at the second. Convert both to decibels, however, and the reports are

nearly the same - 19 1/2 db and 18 db respectively.

A Translation Scale

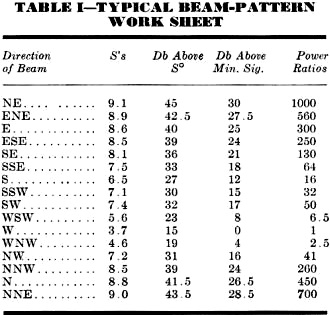

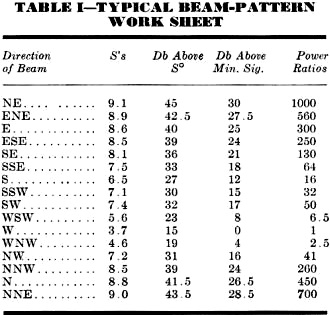

Table I - Typical Beam-Pattern Work Sheet

Fig. 2 provides another tool of great value in checking beams and plotting

radiation patterns. Here the decibel scale again appears, and related directly to

it are power- and voltage-ratio scales. In the last column is the S scale of the

Skyrider SX-17, which happens to be the receiver used at W2JCR. Those having other

receivers should substitute the appropriate S scale.

To illustrate the use of the chart, assume that a rotary beam is being checked.

"On the nose" a reading of S8 is obtained and off the back end the reading is S5.

The db equivalents taken from column 2 are 36 and 21 and the difference is 15 db.

Now referring to column 1 it is seen that 15 db represents power ratio of slightly

over 30, and this is the front-to-back ratio of this particular beam. Thus a specific

and decidedly useful report can be given to the station being checked.

The power ratio could be arrived at immediately without the intermediate conversion

of the S readings to db, but if this is done we get a ratio of something like 3600

to 120, which is rather unwieldy. To reduce it to the simpler terms involves some

mental gymnastics which are much more arduous than the S-db-power conversion scheme.

Although beams are evaluated by hams almost entirely in terms of either db or power

ratios, there are occasions when the voltage ratios are desired and for that reason

they are included in the chart.

Connecting his rotary beam to his receiver, the owner can check its characteristics

by tuning in some other station and noting the meter readings as the beam is rotated.

The conversion to terms of power ratio is then made as described above.

Plotting Patterns

Fig. 3 - A sample rotary-beam directional characteristic

determined by the method described in the text. The curve could be smoothed out

if desired.

Obviously the only additional work necessary for plotting the radiation pattern

of a beam is to take a number of readings as the antenna is rotated, instead of

just the two needed to check front-to-back ratio. There are several precautions

to be taken in such checks, however, and the procedure followed at W2JCR may prove

helpful.

The first thing is to determine the antenna position which puts the strongest

signal into the receiver. If this is above S9 the antenna coupling to the receiver

should be reduced so that the meter reads S9 or slightly lower, thus keeping within

the range of the db calibration. Having found this position for the beam, and with

the receiver antenna coupling suitably adjusted, the exact course of procedure is

then agreed on between the two stations: The beam to be rotated in steps of not

more than 22 1/2 degrees and to be stopped in each of these positions for at least

30 seconds; at each stop the position of the beam to be announced, then the carrier

left unmodulated for the balance of the period.

At the receiver end the selectivity should be high to reduce the possibility

of QRM, because an interfering signal will make the check valueless. Leaving the

antenna coupling at the adjustment mentioned above, at each position of the beam

make a note of the announced direction, then during the unmodulated period make

sure the signal is exactly in tune and note the resulting reading. This retuning

is important because changes in signal strength may otherwise tend to throw the

receiver oscillator slightly out of tune, making readings unreliable. If modulation

were present, that too might confuse the readings by "wobbulating" the meter.1

The meter readings are noted in fractional S points; usually it is possible to estimate

to one-tenth of a point.

Table I is the work-sheet of an actual check made by W2JCR and will be briefly

described to illustrate the orderly method of recording the measurements and compiling

the desired data.

The directions as announced were entered in column 1 and the S readings in column

2. The transmitting station was then asked to stand by for a few minutes while the

desired information was worked out in columns 3, 4 and 5.

In column 3 the db values for the various readings are noted. These are taken

from the second column of Fig. 2. We note that the lowest value here is 15

db, and inasmuch as we are interested only in the relative values shown by this

particular beam we adopt this as a new zero level and deduct 15 from each of the

values in column 3, entering the result in column 4. From these figures we see that

the maximum signal is 30 db above the minimum; that the "head-on" signal is 13 db

above the back (southwest) signal, etc. Incidentally, we note that this beam is

apparently not functioning "according to Hoyle" because it should have minimum radiation

off the ends, which would be the SE and NW positions.

In this particular report the power ratios are entered in column 5. Had the owner

of the beam been interested in voltage ratios these would have been shown instead.

In either case the data are obtained directly from Fig. 2. If a power unit

value of 1 is given to the minimum signal position, then the maximum signal, which

is 30 db up, would represent 1000 times this power, etc.

With these figures completed a detailed report was given to the owner of the

beam by reading off to him the figures of columns 4 and 5. Later, as a matter of

interest, the pattern of his beam was drawn up as shown in Fig. 3, using polar

graph paper.2 Lacking this it could have been drawn on plain paper on

which a dot is first placed to represent the transmitter and lines drawn radiating

from this at angles of 22 1/2 degrees - like the cuts of a pie that has been divided

into 16 pieces.

The scale selected for use depends on the ratios involved. In this case the maximum

is 1000 to 1, so the scale used was 200 per inch, making the front lobe 5 inches

long. The other values were laid out on each of the lines corresponding to the beam

positions and the resulting points were joined together with a line and this made

up the pattern of the beam.

Had more readings been taken, perhaps at every 10 degrees, this pattern would

have been less angular in appearance and more truly representative, because obviously

the actual radiation pattern is not likely to have sharp points such as those shown

at the front and back. Even in drawing the present pattern it would have been entirely

legitimate to round off the corners; in fact this is usual practice although it

is easier to draw as shown in Fig. 3.

Attention has been centered, in this discussion, on the use of the S meter and

the data of Figs. 1 and 2 as aids in checking beams. But they have other applications

as well. Power gain or loss for different degrees of antenna coupling at the transmitter,

and different adjustments of the transmitter or transmitting antenna can be checked

in the same way providing the" before and after" readings are made under similar

conditions of receiver adjustment, line voltage, etc. The effectiveness of any two

fixed transmitting antennas can likewise be determined, especially if they are so

arranged that the transmitter can be switched from one to the other quickly. Such

comparative checks obtained from several receivers located in different directions

from the transmitter will provide helpful information, but the radiation pattern

of a fixed directional beam can be determined in this manner only if the antenna

used for comparison is non-directional or of known directional characteristics.

In conclusion, it is well to emphasize the fact that measurements such as those

described in this article are not perfect. The human element plays an important

part, as in accurately reading the meter, determining the exact angle between different

positions of a beam, etc. A bad tube in the receiver may alter the meter calibration,

but fortunately many of the ailments to which receivers are at times heir, while

they may change the reading of the meter for a given signal voltage input, do not

materially alter the relationship within the scale itself and therefore do not change

the db calibrations given in Fig. 1. In any event, the system outlined represents

the most accurate, generally available method of checking and is far superior to

the old system of "three S's down," "two S's up" now in common use.

In plotting radiation patterns it should be borne in mind that two patterns plotted

on the same beam but by different receivers in different directions will not necessarily

be the same. There are numerous factors, such as reflection, absorption, and refraction,

which may differ in different directions and different locations. But by obtaining

checks from several different stations it is usually possible to strike some sort

of average which will not only indicate the characteristics of the beam but may

indicate specific faults such as a nearby structure which is affecting its operation.

* The NC-100 utilizes an electric eye in conjunction with the r.f. gain control,

which has a 0-10 scale. With a signal tuned in the gain control is backed off until

the signal barely registers on the eye, then the S reading is taken from a curve

plotted in terms of gain-control settings. The combination is therefore the equivalent

of a meter.

** The Super-Pro meter is not calibrated in S-points but instead has a 0-5-milliampere

scale. With the antenna disconnected and no signal tuned in this will read somewhere

around 4. As signals are tuned in the reading drops and it is the amount of this

drop from the normal no-signal level that appears in the figure. Thus if the normal

level is 4.1 and a signal drops it to 3.6, then that signal is 15 db above the "zero"

level, etc.

1 Obviously, when making such a check with a distant station, it is also necessary

to take the effects of fading into account and, if necessary t make the measurements

over a sufficiently long period so that fading averages out. The measurements in

such a case should be attempted only when conditions are relatively stable. - Editor.

2 Polar Coordinate paper No. 358-31. Keuffel and Esser, 127 Fulton St., N. Y.

C.

Posted August 5, 2022

(updated from original post

on 3/31/2016)

|