|

December 1959 Electronics World

Table of Contents

Table of Contents

Wax nostalgic about and learn from the history of early electronics. See articles

from

Electronics World, published May 1959

- December 1971. All copyrights hereby acknowledged.

|

Phosphorous:

From Latin phosphorus "light-bringing," from Greek Phosphoros "morning star,"

literally "torchbearer," from phos "light," contraction of phaos "light, daylight" +

phoros "bearer," from pherein "to carry." Long before mankind had developed methods

of bombarding phosphorous compounds with electron beams to make them glow,

17th-century scientist Hennig Brand observed the characteristic light emitting property

of phosphorous when exposed to oxygen. No doubt the Ancients noticed the naturally

occurring glow of bioluminescent plants and animals, and maybe even luminescent glow

caused by the breaking open of phosphorous-containing rocks. Radioactive decay in the

vicinity of phosphorescent materials can also cause a detectable glow.

Phosphors, the

subject of this 1959 Electronics World article, include both phosphorescent

and luminescent materials, provided the medium for electroluminescent displays like

the cathode ray tube (CRT). Some early electronic display devices used whacky

electromechanical apparati to sling light beams around using whirling plates,

mirrors, and pencil beam light sources. David Fortney, of the Sylvania Electric

Products company, a maker of CRTs and TVs, provides here an introduction to

phosphors.

Phosphors and Their Uses

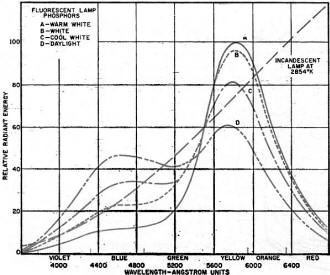

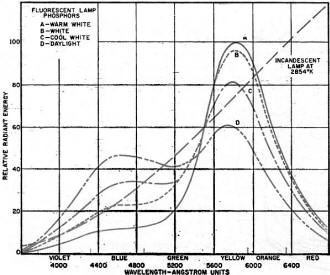

Fig. 1 - Energy distribution of fluorescent lamp phosphors.

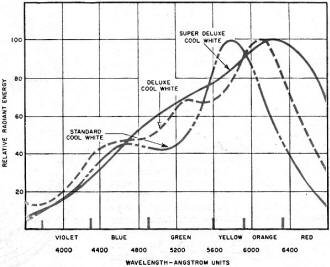

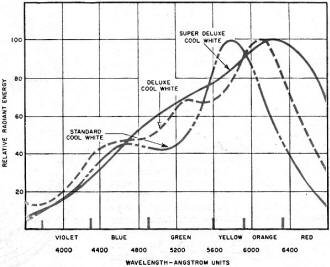

Fig. 2 - Energy distribution of various white lamp phosphors.

By David F. Fortney

Chemical & Metallurgical Div., Sylvania Electric Products Inc.

These remarkable fluorescent powders have made possible great advances in lighting

and in visual communications.

Twenty-five years ago the making and use of fluorescent powders called "phosphors"

or "light bringers" as well as the phenomenon of luminescence, while long well-known

in the laboratory, had little significance to most people. Phosphors had few practical

applications beyond the oscilloscope and the x-ray intensifying screen. We lighted our

homes, offices, and factories with incandescent lamps. We had no television sets in our

living rooms. During these twenty-five years, fluorescent lighting has enjoyed universal

acceptance while the TV set is now a standard item of furniture in the American home.

Luminescence, in lighting and in the television picture tube, has become as commonplace

in our generation as the radio during our parents' time and as the incandescent lamp

from the turn of the century to the first World War.

Phosphors, the light producing powders which make possible these advances in lighting

and in visual communication, are inorganic materials which have the special property

of absorbing energy in the ultraviolet range (lamp phosphors), from fast-moving electrons

(TV picture tubes), or in a changing electric field (electroluminescence). Some of the

energy so absorbed raises the electrons to higher energy states within the phosphor activator

centers. When these electrons return to lower energy states, the energy is released as

radiation of longer wavelength in the visible range of approximately 4000 to 7000 angstroms

(400 to 700 millimicrons), or, in some cases, in the region of 3650 angstroms. This latter

emission may be used to excite organic "black-light" paints or pigments. Visible emission

from phosphors is ordinarily not monochromatic or in a narrow discrete band, but occupies

a wide band having a spectral energy distribution curve of a "mountain peak" shape (see

Fig. 1).

In general, lamp phosphors are inorganic silicates, borates, tungstates, and phosphates,

usually activated by manganese, antimony, tin, or lead. Those used for TV picture tubes

are sulfides of zinc and cadmium activated by silver, while the electroluminescent phosphors

are copper-activated zinc sulfides. Barium silicate is a well-known "black-light" phosphor.

The color of a so-called "white" fluorescent lamp is designated by its color temperature,

so that basically any lamp whose color falls on or near the so called black body line

is considered a "white" lamp.

There has been and there still is considerable confusion for the user because there

are so many varieties of "white" lamps. Table 2 helps clarify the situation and emphasizes

that one of the most important advantages of fluorescent lighting is color control.

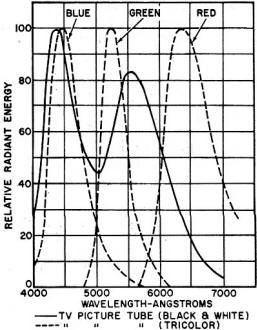

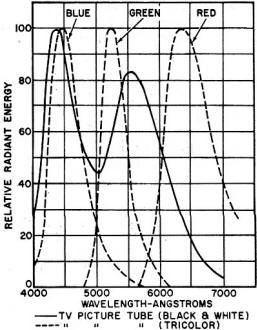

Fig. 3 - Radiant energy of CRT phosphors.

At the present time, by far the most popular lamp is the high efficiency "cool white"

lamp, although large numbers of the other colors are in use for specialized applications.

It should be understood that 4500° "cool white" lamps, for example, all look the

same color to the eye, whether "standard," "deluxe" or "super deluxe." The differences

arise in the appearance of objects under the various lamps. These differences are shown

by a study of the spectral energy distribution curves in Fig. 2, in which the three "cool

whites" are compared. The standard lamp is weak in red and green-strong in yellow. The

"deluxe" is stronger in red and green. In the "super deluxe" lamp, the red is greatly

increased and the colors are better balanced.

In the early days, manganese-activated zinc beryllium orthosilicate was the basic

"white" phosphor used by all lamp makers. Actually this material is not a single phosphor,

but a family of phosphors. By varying the Zn/Be ratio and the manganese content, the

color could be varied from a brilliant green through white to a pinkish color. Blue-white

magnesium tungstate was blended with the silicate to adjust the color as desired.

Other important lamp phosphors which have been used for some years, either as color

correction phosphors for white lamps or for the production of colored fluorescent lamps

or sign tubing, are given in Table 1.

At present, the blue-white magnesium tungstate has been largely replaced by titanium-activated

barium pyrophosphate, and the other blue tungstates by strontium pyrophosphate, tin activated.

Both of these important phosphors were developed in Sylvania's laboratories.

Because of the toxic nature of, the zinc beryllium silicate, the lamp industry in

America and England completely discontinued its use in 1948, although it is still being

used in some projection-TV picture tubes. Almost overnight, calcium halophosphate activated

by antimony and manganese ("halo" because it contains the halogens, chloride and fluoride)

was used exclusively. Like the silicate system, it is not a single phosphor, but a complex

family in which some color variations can be made by changes in "mol ratios" or activator

concentrations. The primary activator, manganese, gives rise to the emission of a red

band, in conjunction with the secondary activator or sensitizer, antimony, emitting in

the blue region.

This month's cover shows a number of piles of

Sylvania phosphors employed in the electronics and lighting industries. Under normal

illumination these materials look like ordinary white powder. However, when illuminated

by ultraviolet or when a thin film of the powder is excited by an electron beam, light

of various colors is produced. In photographing our cover, we illuminated the white phosphor

piles with four 15-watt ultraviolet lamps in order to produce the colorful effect shown.

A yellow filter was used for color correction to remove the bluish cast that would have

been produced. This month's cover shows a number of piles of

Sylvania phosphors employed in the electronics and lighting industries. Under normal

illumination these materials look like ordinary white powder. However, when illuminated

by ultraviolet or when a thin film of the powder is excited by an electron beam, light

of various colors is produced. In photographing our cover, we illuminated the white phosphor

piles with four 15-watt ultraviolet lamps in order to produce the colorful effect shown.

A yellow filter was used for color correction to remove the bluish cast that would have

been produced.

Probably the most common use of phosphors is in the ordinary fluorescent lamp shown

at the lower left of the cover. When current passes through the lamp, some ultraviolet

radiation is produced. This excites the phosphor that coats the inside surface of the

long glass tube. As a result, the phosphor glows brightly and gives off visible light.

The three electron tubes shown on the cover are all RCA types that employ various

types of phosphors. The tube at the lower right-hand corner is the 21CYP22 color picture

tube. This is the conventional three-gun shadow-mask type that uses a tricolor phosphor-dot

screen. The screen is composed of an orderly array of small, closely spaced, phosphor

dots arranged in triangular groups, or trios. Each trio consists of a green-emitting

dot, a red-emitting dot, and a blue-emitting dot, and is aligned with a corresponding

hole in the shadow mask. When the three electron beams in the tube cause these dots to

be illuminated in various mixtures and combinations, a full-color picture is produced

on the screen.

Directly above the color picture tube is a type 7448 display storage tube. This 5-inch

tube produces a bright, non-flickering display of stored information for as long as 40

seconds after the image has first been produced. The tube utilizes two electron guns

- one for writing and the other for viewing. The writing gun produces a beam that applies

the pattern to a thin storage grid located just behind the tube's faceplate. The pattern

is in the form of a distribution charge on this grid. Then a high-current, low-velocity

beam from the viewing gun transfers the charge pattern on the storage grid to a highly

efficient phosphor screen where an intense visible pattern is produced. Because of the

high efficiency of the phosphor and the fact that it is continuously excited, rather

than intermittently as in ordinary CRT's, a very bright, non-flickering display is produced.

Just to the left of the color picture tube is a small type 7404 image-converter tube.

This tube is used with suitable optical systems for viewing an object or specimen irradiated

with ultraviolet radiation, as in ultraviolet microscopy. The object to be viewed is

focused by optical means on a semi-transparent photo-cathode at one end of the tube.

Electrons from this image are electrostatically focused on the fluorescent electron-optical

methods. The resultant reduced image can then be viewed with an optical magnifier.

These are just a few of the many interesting and important uses to

which phosphors can be put. (Photo by Bruce Pendleton)

(1) Type 7448 display storage tube. (2) The 7404 image-converter

tube. (3) The 21CYP22 color picture tube.

As color rendition became a more important factor in lighting, the calcium silicate

phosphor was used as the major component in the deluxe series of phosphors. In 1954,

the super deluxe cool white lamp was introduced, which provides the best rendition of

color yet obtained with fluorescent lamps. The basic phosphors for this lamp, both developed

by Sylvania, are calcium strontium orthophosphate activated by tin, subsequently replaced

by the brighter calcium zinc orthophosphate: tin activated. In 1956, in response to demands

for higher illumination for virtually all seeing tasks, Sylvania introduced the VHO (Very

High Output) lamp, which produces two and one-half times as much light as conventional

lamps of the same dimensions. This important development makes possible the extension

of fluorescent lighting into medium and high bay industrial lighting, as well as for

outdoor applications such as street lighting, parking lots, etc.

While each lamp contains only a few grams of phosphor, the amount of phosphor required

by the industry each year adds up to many tons. The phosphor is applied to the inside

of the lamp as a lacquer suspension, from which, after the solvent has evaporated, the

lacquer is baked out, leaving the phosphor adhering to the glass in a smooth, uniform

coat. The raw materials for phosphors must be of exceptional purity. Accordingly, purification

procedures are always a vital part of the precipitation of phosphors or phosphor component

raw materials. In general these are made as pure as possible, then the desired amount

of activator added in the form of a suitable compound. Control of crystal structure and

crystal size distribution are also important in many materials used in compounding the

phosphate phosphors. Phosphors are usually prepared by the homogeneous dry mixing of

the purified constituents in the required proportions, followed by a heat treatment in

the range of 1800 to 2000°F. Oft times control of the atmosphere is necessary during

such "firing" to provide oxidizing, reducing, or inert conditions in the furnace.

Television picture-tube phosphors are largely zinc or zinc cadmium sulfides with a

range of activators such as silver to secure the color, brightness, and efficiency desired.

(See Fig. 3) The phosphor screen is formed on the inner face of a picture tube by allowing

the powder to settle from a water suspension containing a little potassium silicate and

barium acetate. Cathode-ray-tube phosphors, as used in industrial and military tubes,

are made in a range of colors and persistence characteristics essential for rapidly changing

displays or longer time presentations. (Refer to our cover story for additional details.

- Editor.)

The newest family of phosphors, electroluminescent phosphors, are used in solid state

"cold light" lamps manufactured under the name "Panelescent" by Sylvania.1

These phosphors are already manufactured in ton quantities for applications such as in

automobile instrument panels, night lights, and highway signs. These phosphors are largely

zinc sulfide having activators such as lead or copper. "Panelescent" lamps are made by

imbedding the phosphors in a ceramic glaze resulting in years of continuous service at

low cost.

As new needs arise in the lighting and electronics industries, the development of

suitable phosphors to meet these needs will also continue.

References

1 Martin, A. V. J.: "Electroluminescence - Light of the Future," Radio & TV News,

January, 1958.

|