|

January 1939 Radio-Craft

[Table

of Contents] [Table

of Contents]

Wax nostalgic about and learn from the history of early electronics.

See articles from Radio-Craft,

published 1929 - 1953. All copyrights are hereby acknowledged.

|

Modulating a light beam for secure

communications was not a new concept is 1939 when Gerald Mosteller invented his

device, but doing so with inexpensive equipment, using "outside-the-box" thinking,

was new. Exploiting the relatively recently discovered physical phenomenon of "skin

effect," his system used a specific range of frequencies to modulate the filament

of a standard flashlight type incandescent light bulb that could effect temperature

changes - and therefore intensity changes - rapidly and of significant amplitude

to transmit information in the audio frequency range. Mr. Mosteller's contraption

evolved as the result of a college thesis project. There does not exist a plethora

of modern-day modulated light communications systems using incandescent bulbs as

the source, so it is safe to assume insurmountable physical and/or financial obstacles

prevented it from going mainstream. There are, of course, many modulated light communication

devices in use, but primarily at infrared and ultraviolet wavelengths.

The Skin Effect Talking Lightbeam

Gerald Mosteller, University of Southern California graduate,

is shown with a portion of his apparatus for sending sound over a lightbeam, using

an ordinary 5-cent flashlight bulb and simplified radio parts. His discovery formed

the thesis for his Master's degree at the University.

By Gerald Mosteller

The University of Southern California has cooperated in making available to Radio-Craft

readers this first detailed description of the principle and equipment comprising

the "skin-effect" lightbeam telephone discovery of a U. of S. C. graduate. Anyone

can easily duplicate Mr. Mosteller's experiment.

A new means of transmitting sound over a beam of light by use of amplifiers and

an ordinary 5-cent flashlight bulb constituted the writer's thesis, for his Master's

degree at the University of Southern California last June.

This simplified form of sending music, voice and other sounds over a lightbeam,

discovered during studies in Physics, has been the subject of experiments by scientific

laboratories over the country with expensive equipment for a period of years.

Its use in secret communication by the army and navy, landing of airplanes with

lights that penetrate fog, and adaptability by automobile races in communicating

with their pits, are given among possibilities.

In contrast to radio communications, messages cannot be intercepted except by

instruments set up directly in the beam of light. By using infra-red filters an

invisible beam can be created which further prevents interception.

How it Works

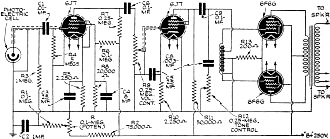

By means of a radio-frequency oscillator and equipment similar to that of the

ordinary home radio set, sound is amplified and the output caused to modulate the

oscillator.

A "skin effect" is created on the surface of the light filament and instead of

heating the entire filament as heretofore, the current travels along the surface

. Thus the filament may change temperature fast enough to transmit sound.

Skin Effect

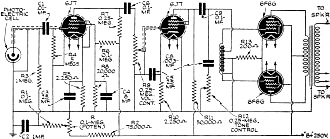

The receiver consists of a photoelectric cell "detector" followed

by 3 stages of A.F. amplification. Condenser C1 and resistors R3 and R4 are mounted

directly behind the P.E. cell in the reflector.

The transmitter consists of a speech amplifier, oscillator and

ordinary flashlight bulb. The A.F.-modulated current flows along the surface of

the filament (skin-effect) causing rapid fluctuations of the light intensity (which,

in turn, are translated into intelligibility by the receiver).

Skin effect is a phenomena of alternating currents. The maximum inductive reactance

in a wire or filament is at its axis. In general the inductance offered to other

filaments of current decreases as the distance from the axis increases. Thus the

current is distributed so that it is greatest near the surface. The heat generated

by this current is proportional to the square of the current. The heat is radiated

from the surface, conducted to the cooler center and used in raising the temperature

of the filament.

The high-frequency alternating current (radio-frequency) causes the skin effect,

the modulation of this current varies the surface temperature of the filament so

that the light varies with the modulation. The conductivity of the metal carries

the surface heat toward the center of the filament when the modulated current is

great, thus allowing the surface to cool more rapidly so the radiation may follow

the modulated current down. This improves the audio response at high frequencies.

A curve was drawn to show the advantage due to skin effect. It was shown as a percentage

of the oscilloscope readings of a sine wave at some frequency compared with the

reading at 768 cycles per second. This curve of the efficiency of lightbeam modulation

was measured on an oscilloscope having its vertical sweep connected to the output

of the receiver. The input to the oscilloscope was a beat-note oscillator connected

to the transmitter.

A photoelectric cell is mounted in the focus of a parabolic reflector which may

be made from an electric heater by removing the heating element. The particular

heater purchased was selected after testing several because it concentrated rays

from a distant light at a very small area. It is necessary that the rays focused

by the parabola form a sharp-pointed cone of light which can get into the curved

plate of the cell rather than hit on its outside edge.

Directly behind the cell is mounted a midget 0.01-mf. coupling condenser, C1;

a 1-meg. resistor, R3, through which the cell receives its positive voltage and

the 5-meg. resistor, R4, which is the grid resistor for the 1st tube. The shielding

afforded by the metal reflector and the wire shield in front of it is enough for

shielding these elements, however they might be further shielded to cut down A.C.

hum by wrapping them in tinfoil and grounding the foil.

Similar phenomena have been developed before by means of high-voltage equipment

and the use of cathode-ray and neon lights, but never before with simple equipment

including the use of a "nickel" (5c) battery lamp.

The 12-meter grid coil is wound with 18 turns of No. 14 enamel-covered wire on

an air core 2 x 1/2-in. inside dia. The 12-meter plate coil has 12 turns of E.C.

wire on a 1 1/2 x 3/4-in. dia. air core; the coupling to the Mazda-lamp circuit

is accomplished by means of a single turn of No. 14 E.C. wire around the center

of the plate coil.

One position of the S.P.D.T. switch connects the mike through a 4 1/2 V. mike

battery, the other cuts the battery out so a low-impedance phono pickup may be used.

The single-button carbon mike used had low impedance.

List of Parts

Transmitter

- One American type SB single-button carbon microphone, hand type;

- One Yaxley No. 75 phone plug;

- One Yaxley No.1 phone jack;

- One H&H S.P.D.T. toggle switch;

- One u:r.c. No. CS6 microphone input transformer;

- One Aerovox No. PR25 condenser, 10 mf., 25 V.;

- One Cornell-Dubilier electrolytic condenser, 4 mf., 450 V.;

- One Yaxley No. M25MP volume control potentiometer, 0.25-meg.;

- One I.R.C. type B1 carbon resistor, 1,250 ohms, 1 W.;

- One I.R.C. type B1 carbon resistor, 1,500 ohms, 1 W.;

- One U.T.C. No. C823 class B input transformer, 6A6 plates to two 6A6 grids;

- One U.T.C. No. CSR modulation transformer, 6A6 plates to 30,000 ohms;

- One Ohmite "Red Devil" resistor, 400 ohms, 10 W.;

- One Aerovox type 484 tubular condenser, 0.001-mf.;

- One National type R100 high-frequency R.F. choke;

- One Cardwell "Midway" type MR50BD split-stator condenser, 50 mmf, both sections;

- Three Sylvania type 6A6G tubes;

- One Eveready "Mazda" spotlight reflector and light bulb;

- One chassis and hardware;

- One power supply, 450 V., 100 ma.;

- Two 12-meter coils (see text).

Receiver

- One RCA PE. cell, No. 921;

- One Aerovox No. 450 condenser, 0.01-mf., C1;

- One Aerovox type 484 paper condenser, 1 mf., 400 V., C2;

- Two Aerovox type PB25 electrolytic condensers, 25 mf., 25 V., C3, C5;

- One Cornell-Dubilier electrolytic condenser, 8 mf., 200 V., C4;

- Two Aerovox type 484 tubular condensers, 0.1-mf., 400 V., C6, C9;

- One Aerovox type 484 tubular condenser, 0.003-mf., 400 V., C8;

- One Yaxley L potentiometer, 0.1-meg., R;

- Two I.R.C. B1 carbon resistors, 0.1-meg., 1 W., R1, R6;

- One I.R.C. B1 carbon resistor, 75,000 ohms, 1 W., R2;

- One I.R.C. B1/2 carbon resistor, 1 meg., 1/2-W., R3;

- One I.R.C. B1/2 carbon resistor, 5 megs., 1/2-W., R4;

- Two I.R.C. B1 carbon resistors, 2,250 ohms, 1 W., R5, R10;

- One I.R.C. B1 carbon resistor, 0.25-meg., 1 W., R7;

- One I.R.C. B1 carbon resistor, 20,000 ohms, 1 W., R8;

- Two Yaxley type M potentiometers, 0.25-meg., R9 (volume control), R12 (tone

control);

- One I.R.C. B1 carbon resistor, 50,000 ohms, 1 W., R11;

- One ohmite "Red Devil" resistor, 200 ohms, 10 W., R13;

- Two Sylvania type 6J7 tubes;

- Two Sylvania type 6F6 tubes;

- One Thordarson tapped input choke, No. T7431;

- One Wright DeCoster permanent-magnet magnetic loudspeaker, with output transformer

to 6F6's in push-push class B; One power supply, 250 V., 80 ma.

|