|

December 1942 Radio-Craft

[Table

of Contents] [Table

of Contents]

Wax nostalgic about and learn from the history of early electronics.

See articles from Radio-Craft,

published 1929 - 1953. All copyrights are hereby acknowledged.

|

Homodyne reception, although

we don't often refer to it today using that term, involves mixing the modulated

signal with a local oscillator that is tuned to the same frequency so that the demodulated

signal is at baseband. In other words, the result of a homodyne nonlinear mixing

process is a sum frequency of 2x the signal input and the difference frequency is

DC (at the low end of the modulation). That is a simplistic explanation, and this

1942 Radio-Craft magazine article goes into a little more detail about

methods, advantages, and disadvantages. Why not just make things simple and make

every receiver a homodyne circuit? The answer is that with homodyne operation every

theoretically possible mixer spurious product will fall inband without any means

of filtering them out. Sometimes it doesn't matter, but especially in today's crowded

radio spectrum it just is not workable because the interference level would be too

intolerable.

Homodyne Reception

Interference and effect of bias in diode detection. The diode

conducts during the parts of the cycle are shown shaded.

Possibilities of the System as an Aid to Selectivity

The "homodyne" system of reception is a little-known member of the family of

radio "dynes," so let us first see how it is related to its cousins heterodyne,

super (sonic) - heterodyne and autodyne. The word "dyne" is derived from the Greek

for power, so that heterodyne merely means putting in energy at a different frequency,

and becomes "supersonic-heterodyne" if the frequency difference is greater than

audible (e.g. 465 kc/s), while autodyne means putting in its own power, i.e. a self-oscillating

detector. Similarly, homodyne means that energy is put in at the same frequency,

i.e. in synchronism with the carrier of the signal which it is desired to receive,

and this is the system which may be able to help us with the selectivity problem.

Interference

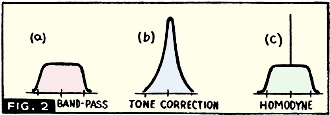

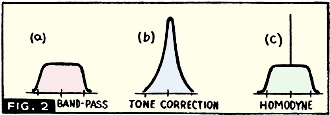

Homodyne reception compared with other methods of obtaining selectivity.

Note the similarity of homodyne reception to the bandpass curve.

Interference can be divided into two categories, the type which involves the

carrier of the wanted signal, and the type which does not. In the first category

we have the direct heterodyne between the wanted carrier and a neighboring carrier,

"side-band splash" which consists of heterodynes between the wanted carrier and

the side-bands of the interfering signal, and cross-modulation; in all of these

the output of interference is merely proportional to the weaker of the two frequencies

which are beating together so that increasing the strength of the wanted carrier

makes no difference to the interference. Before, we can benefit from the homodyne

principle, therefore, adjacent carriers must be spaced far enough apart for the

heterodyne note to be outside the audio-frequency band, or alternatively the heterodyne

must be eliminated by means of a "whistle filter" of some sort. The latter alternative

is not the ideal solution, since it involves eliminating the same frequency (or

rather a band of frequencies) from the program; but if the filter has a narrow enough

attenuation band, it may be a tolerable method. It seems likely to take a very tong

time to produce sufficient public demand for high-fidelity broadcasting on the medium-wave

band to secure the sacrifice of a number of stations to adequate spacing of channels;

in fact, it is a debatable point whether the introduction of wide-band U-H-F broadcasting

would render superfluous high fidelity on the medium-wave transmissions, or whether

the experience of really good quality would lead to a demand for it on all transmissions.

Assuming, however, that we have by some means eliminated the adjacent-channel heterodyne,

and taken the necessary precautions against cross-modulation (which means practically

building a receiver with RF stages that never overload), the residual interference

will consist of the whole modulated signal (carrier plus side-bands) of a transmitter

on a neighboring frequency.

Selectivity Limitations

There is an essential distinction between the wanted and unwanted signals, by

reason of the fact that they have different carrier frequencies, and so it may be

possible to eliminate the interference which consists solely of the independent

signal more effectively than heterodynes, etc., which involve the carrier of the

desired signal. But first one must answer the natural question, why selective circuits?

Now, reasonable program enjoyment requires a signal/interference ratio of 40 db.,

and for high-fidelity reception the ratio should be 60 db., i.e. a voltage ratio

of 1000: I; add to this the condition that ideally one should be able to receive

the weaker of two adjacent stations, say with a field-strength ratio of 10: I, and

if the reader then thinks it is easy to design a receiver with adjacent-channel

selectivity of 10,000: I, he need not worry about homodyne receivers.

Linear Detectors

The phenomena underlying homodyne reception actually occur to some extent in

every receiver using a linear rectifier; (that is to say almost every modern receiver

that has a reasonably strong signal tuned-in); one of the phenomena is that a linear

rectifier is most sensitive to signals that are in the same phase as the strongest

signal out of several applied to it. In the ordinary-diode rectifier, the diode

is automatically biased by the signal so that it is only conducting for a small

part of the cycle, say the extreme positive values of the voltage wave, as shown

in Fig. 1. If now the amplitude of the signal is varied by modulation, there

will be a change in the height of the voltage-peaks, therefore an increase or decrease

of diode conduction, and this in turn will change the bias voltage so that conduction

occupies the same proportion of the whole cycle as it did for the original amplitude.

But the bias voltage on the diode is in fact the rectified output, so that variation

of this voltage with the input represents an output signal proportional to the amplitude

modulation of the input signal.

Detector Discrimination

Now suppose there is added to the input a smaller signal, at a different frequency,

as suggested by the dotted curve in Fig. 1. The first positive peak of this

second signal falls fairly well on the conduction period (determined mainly by the

strong signal) and therefore increases the rectified current; but, the second positive

peak falls in a non-conducting period and therefore cannot affect the output, while

the second conduction period is accompanied by a negative peak of the smaller signal,

which reduces the rectified output and so tends to oppose the effect produced in

the first conduction period. It is obvious that the weaker signal has relatively

little effect if of different frequency from the stronger one, since it is the latter

which decides when the diode is conducting: as often as not the weaker signal comes

up positive when the diode is thoroughly cut off by the. stronger signal, and on

those occasions when the diode is conducting, the weaker signal is as likely to

be negative as positive. This is only a very rough picture of the action, because

the frequency-difference is greatly exaggerated in Fig. 1, and no allowance

is made for changes in duration of the conduction periods when the weak signal reaches

a maximum or minimum near the edge of a conduction period; when it has been properly

worked out mathematically, the ratio of the AF outputs due to modulation on the

strong signal S and on the weak signal W is approximately 2S2/W2,

and the phenomenon is known as "the apparent demodulation of a weak signal by a

strong one" (or, more briefly, "rectifier discrimination"). To see how useful this

is, suppose that by means of selective circuits we have made the wanted station

supply a carrier voltage 10 times greater than that of the unwanted station at the

input to the detector: this represents a signal/interference ratio of 20 db., which

would not be very good. But if S/W = 10, the ratio of the audio-frequency output

voltages is 2S2/W2 = 200, or 46 db., which is tolerably satisfactory.

Selectivity and Tone Correction

In early receivers this gain from linear detection was not always obtained, because

the signal level at the detector was so small that the detector did not function

as an on/off device, as described in connection with, Fig. 1, but as an approximately

square-law device which conducted rather better in one direction than the other;

since the stronger signal was thus not sufficient to stop conduction for part of

the cycle, the weaker signal could always produce some effect, regardless of its

phase relation to the stronger signal, and no rectifier discrimination was obtained.

One of the first specialized systems to obtain this advantage (though the mechanism

was not at first understood) was the "tone-correction" type of receiver. The RF

circuits (including the RF, if any) were made. of maximum Q, so that a very high

gain was obtained at carrier frequency and low modulation frequencies, though the

higher sidebands were relatively cut by a very large amount, and after detection

the severe top cut was corrected by AF tone-correction circuits.

Rectifier Discrimination

Owing to the strong carrier, this gave good "rectifier discrimination," but the

top boost in the AF circuits exaggerated any harmonics produced in the process of

rectification or by asymmetry of the RF circuits: 2 per cent to 5 per cent of harmonics

in the output of the detector could become something like 50 per cent harmonics

in the loudspeaker, and the popularity of this system was short-lived. In fact,

it died a natural death with the development of the super-heterodyne and AVC; the

latter required a large enough amplitude at the detector to insure linear rectification,

while the former provided the means of getting sufficient gain, and at the same

time made it technically feasible to use selective band-pass circuits with a square-topped

response, giving good adjacent-channel selectivity without requiring tone-correction.

But good tuned circuits are expensive and critical in adjustment, even when they

work at a fixed intermediate frequency, and of recent years the number of high-powered

transmitters has been greatly increased, so that once again selectivity, is a problem.

The tone-correction system was on the right track, but the top boost in the AF circuits

was an intolerable nuisance; the solution then appears to be to increase the amplification

of the carrier only, while retaining a uniform amplification for all the sidebands

from lowest to highest, and this is the homodyne system. The three systems are represented

diagrammatically in Fig. 2: diagram (a), normal receiver with square-topped

response curve; (b), sharp circuits requiring subsequent tone-correction; and (c),

homodyne receiver with carrier only accentuated. If wanted and unwanted signal reach

the detector with equal amplitudes, the result will be a hopeless jam; but if we

can add to the desired signal an artificial carrier of just over 30 times the existing

carrier strength of either, we immediately obtain a rectifier discrimination 2S2/W2

equivalent to 66db., and reception is perfect, without any disturbance of the audio-frequency

response characteristic. In fact, the audio-frequency performance is improved, because

an incidental advantage of the homodyne system is the elimination of one source

of distortion in the detector. With a normal diode detector feeding a load circuit

whose AC impedance is less than its DC resistance, distortion occurs when the depth

of modulation exceeds some value such as 75 per cent (depending upon the ratio of

AC to DC load); but when the carrier has been artificially increased for homodyne

reception, the depth of modulation will always be small, so that the ratio of AC

to DC detector loads is no longer critical.

Artificial Carrier

The problem, of course, is how to produce this artificial carrier, which must

be exactly in phase with the original carrier of the wanted signal, and there are

two main lines of attack. According to one method, the carrier is selected from

the input by some form of filter, and amplified more than the sidebands. There are

various methods of inserting the filter in the circuit, and a method of selective

negative feedback has been suggested as suitable (Patent No. 533784, abstract published

in Wireless World, Jan., 1942); but this does not go far towards solving the problem,

for the filter still has to have a very narrow response, even if it is connected

in the negative-feedback line instead of in a straight-forward coupling between

two stages of amplification. It can be assumed that the receiver is a superhet.,

and probably the IF will be 465 k.c. while the lowest audio-frequency can be put

at 50 cycles per second. (Any rise in the response to frequencies below 50 cycles

per second can be easily offset by a falling-off in the characteristics of loudspeaker

and AF amplifier.) The carrier-selecting filter must therefore have a band-width

of not more than 50 cycles per second in 465 k.c./s which is a fairly difficult

proposition even for a crystal filter. In addition, the intermediate frequency must

then be correct to something like 20 cycles per second, which means that both the

accuracy of tuning and the stability of the local oscillator must be as good as

20 parts in a million for the higher-frequency end of the medium-wave band, and

proportionately better for short-wave working.

The other line of attack is to use a local oscillator, somewhat similar to the

IF beat oscillator used for CW reception, to generate the extra carrier voltage,

and synchronize this oscillator with the signal carrier. Probably most experimenters

have done this at some time or another with a receiver using a reacting detector:

if the reaction control is smooth enough, reception free from beat note can be obtained

although the set is gently oscillating. But this is not really a fair example of

homodyne reception, since it involves also a great increase of Q of the tuned circuit,

and hence loss of high audio frequencies, which would not be present with a separate

oscillator. In any case, this is hardly a method of reception to let loose on the

general public. But granted the use of a superhet circuit and a separate oscillator

tube for generating the carrier, which is then a practically constant frequency,

there are possibilities in the way of designing the oscillator specially so as to

hold synchronism over as wide a range of frequency as possible, though even so,

tuning would need to be exceptionally accurate, and oscillator drift small. One

of the troubles is that on 100 per cent modulation the carrier of the signal to

be received falls to zero, and the homodyne oscillator would then be almost certain

to drop out of synchronism. (Some data on the effect of modulation on the synchronization

of an oscillator were published by Eccles and Byard in an article in Wireless Engineer,

Jan., 1941, Vol. 18, p. 2.) Another snag is that the artificial carrier from the

local oscillator would predominate in the output from the detector, so the DC component

could not be used for AVC, which would have to be derived from an independent IF

circuit free from carrier injection.

Possibilities of Development

It is clear that a good deal of development would have to be done before a commercial

broadcast receiver could be built on the homodyne principle. (Perhaps the problem

might appeal to some of the amateurs whose transmitters are close down "for the

duration.") But the whole history of radio is the development of tricky laboratory

apparatus into something approaching a foolproof piece of household equipment. For

example, think back to the days of the earliest receivers and compare them with

the present-day superheterodyne. Instead of single-knob tuning and a dial engraved

in k.c., meters, and station names, one used to have two dials, marked only in degrees,

which had to be simultaneously at the correct setting before any but the local station

could be received. Instead of AVC to keep a constant output level, there used to

be a reaction control which usually needed progressive adjustment as one tuned round

the waveband, in order to keep a high level of sensitivity. Instead of independent

volume and tone controls, there would probably be a reaction control supplemented

by a rheostat in the filament of tile RF tube to control gain, and the expert would

balance reaction and gain adjustments to secure the desired volume and band-width.

Looking at this transformation of the radio receiver, and the parallel transformation

of the television receiver from a 3D-hole scanning disc in front of a neon lamp

into the cathode-ray type of receiver, it does not seem unduly optimistic to say

that the difficulties inherent in the homodyne system of reception could be overcome

in a commercial design.

-Wireless World (London).

Posted December 14, 2023

|