|

September 1935 Radio-Craft

[Table of Contents] [Table of Contents]

Wax nostalgic about and learn from the history of early electronics.

See articles from Radio-Craft,

published 1929 - 1953. All copyrights are hereby acknowledged.

|

Edwin Armstrong, often referred

to as Major Armstrong due to his commission in the U.S. Army Signal Corps, came

up with a working scheme for wideband frequency modulation (FM) in the early 1930s.

He did not, as believed by many, invent FM. Narrowband FM was explored in the 1920s

as a replacement to amplitude modulation (AM) in hopes that it would eliminate the

susceptibility to static that AM suffered, but no significant improvement was achieved. When

this article was published in Radio-Craft magazine 1935, it was a mere two years after Armstrong was

awarded patents for his wideband FM system. AM was still the scheme used by

all commercial broadcast stations primarily because receivers were not being

manufactured yet. On January 1, 1941, the

Federal Communications Commission (FCC) allocated a band of 40 channels

spanning 42–50 MHz for FM broadcasting. Radio station WSM-FM (W47NV) in

Nashville, Tennessee, becoming the first fully licensed commercial FM station. Edwin Armstrong, often referred

to as Major Armstrong due to his commission in the U.S. Army Signal Corps, came

up with a working scheme for wideband frequency modulation (FM) in the early 1930s.

He did not, as believed by many, invent FM. Narrowband FM was explored in the 1920s

as a replacement to amplitude modulation (AM) in hopes that it would eliminate the

susceptibility to static that AM suffered, but no significant improvement was achieved. When

this article was published in Radio-Craft magazine 1935, it was a mere two years after Armstrong was

awarded patents for his wideband FM system. AM was still the scheme used by

all commercial broadcast stations primarily because receivers were not being

manufactured yet. On January 1, 1941, the

Federal Communications Commission (FCC) allocated a band of 40 channels

spanning 42–50 MHz for FM broadcasting. Radio station WSM-FM (W47NV) in

Nashville, Tennessee, becoming the first fully licensed commercial FM station.

"Frequency Modulation" in Tomorrow's Set

Major Armstrong's new system of transmission which offers so many possibilities

in the elimination of fading and static depends upon "frequency modulation"; explained

here by the author.

M. J. Cutter

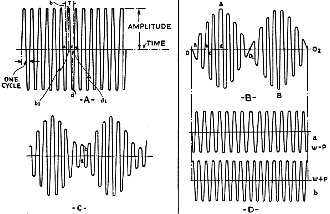

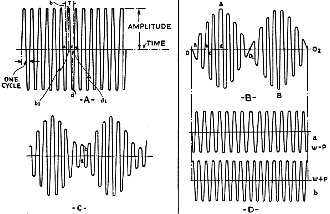

Fig. 1 - The effect of amplitude modulation on the "carrier."

High-frequency currents generated by the oscillator of a modern radio transmitter

have practically a pure sinusoidal form (sine wave), deviations from this form being

corrected by adequate filtering systems. The pure sinusoidal current radiated from

the antenna is commonly called the "carrier." The existence of the carrier can be

detected by the receiver, generally through variations in the plate current. However,

without the aid of high-frequency current from a local oscillator, the carrier cannot

be transformed into an audible signal. As a figurative expression we might say that

the "carrier" is similar to a blank sheet of paper - it is there but it does not

carry a message. In order to perform this latter function the "carrier" must be

modulated. By modulation we mean a continuous variation of the carrier from one

set of conditions to another.

The carrier, having a pure sinusoidal form, has 3 independent characteristics

(like all pure alternating currents): (1) amplitude, (2) frequency and (3) phase.

Any of these elements can be varied in accordance with the frequency or the amplitude

of an audible current, and, therefore, we distinguish three forms of modulation,

namely: (1) amplitude modulation, (2) frequency modulation, and (3) phase modulation.

(It may also occur that the modulating current will cause continuous variations

in more than one element; for instance, there may be simultaneously a variation

of the amplitude and the frequency. The modulation then will be of the "mixed" type.

However, we will limit this discussion to the simple forms in which only one factor

varies.

Amplitude Modulation

All present-day broadcast stations use amplitude modulation, the action of which

is described here. Figure 1A gives us an idea of a carrier before it is modulated.

We see that the current during any cycle, the duration of which is T, starts with

zero value (point a), increases gradually reaching a maximum value bb' at b' which

corresponds to 1/4 of the period T. Then it decreases gradually until it reaches

zero at T/2 (point c). After that the current becomes negative and at point d',

or 3/4T, reaches a maximum value dd', which is equal to bb' but has an opposite

direction. During the last quarter of the period T the current gradually decreases

and becomes zero again (point e). The cycle is now completed. The value bb' (or

dd') is the amplitude and remains the same for any cycle as long as the carrier

is not modulated.

Figures 1 Band C show two carriers of frequency for each modulated by an audio

current of which the frequency f1, is considerably smaller than fo. On

the time. axis, (Fig. 2B) ab represents the period of the carrier while the

period of the modulating current is given by 00102. We see

that during the period 00102 the amplitude of each R.F. cycle

is no more a constant. It has a maximum value at A and B and becomes zero at 01.

In this case we say that the R.F. current is completely modulated. On the other

hand, the amplitude of the current shown in Fig. 1C never becomes zero, although

it has a minimum value at a. Such a current can be considered as a combination comprising

(a) a completely modulated current and (b) an unmodulated carrier.

A mathematical analysis shows that a completely modulated carrier can be considered

as consisting of two unmodulated waves. The frequency of one of these waves is equal

to fo + f1, and the frequency of the other is fo -f1. The

amplitude of both waves is equal to 1/2 the amplitude of the carrier. As an example,

let us consider the case of a 1 megacycle carrier completely modulated by a 1,000

cycle audio frequency. Here fo = 1,000,000 and f1 = 1,000.

The frequencies of the two waves are then 1,000,000 + 1,000 = 1,001,000 and 1,000,000

- 1,000 = 999,000. These two waves are commonly called "sidebands."

When the R.F. carrier is modulated by more than one audio frequency the resulting

current can be considered as the sum of elements of which everyone results from

the modulation of the carrier by one of the audio-frequency currents. The number

of sidebands will be twice the number of modulating frequencies. When the modulating

current of the example just mentioned has a second and third harmonic the frequencies

of which are respectively 2,000 and 3,000 cycles, the modulated current can be considered

as consisting of 6 waves having the following frequencies: (1) 1,003,000; (2) 1,002,000;

(3) 1,001,000; (4) 999,000; (5) 998,000, and (6) 997,000 cycles. In order to operate

without distortion a radio receiver has to be capable of receiving simultaneously

the six sidebands with the same efficiency - a condition which excludes sharp tuning.

Together with the sidebands, a portion of the carrier is also transmitted when the

latter is not completely modulated.

It may seem at first glance that the unmodulated carrier is useless and that

its suppression is desirable. A closer examination, however, shows that the two

sidebands alone cause a beat, in the receiver, the frequency of which is twice the

modulating frequency. In other words, such a modulation would lead to doubling the

pitch of the transmitted sound (a condition which hardly conforms with good transmission!).

The presence of the unmodulated carrier corrects this effect. Each of the sidebands

"heterodynes" (produces a beat frequency) in the receiver with some portion of the

carrier and the result is a beat note of the modulating frequency. Only a negligible

portion of the two sidebands heterodynes together to produce an audio signal of

double frequency. The above consideration explains why the modulation does not usually

exceed some 35 per cent when high-quality broadcasting is desired. It is obvious

that the carrier can be suppressed without affecting the quality of transmission

if the receiver itself can supply the carrier from a local oscillator. Successful

experiments have also been conducted on transmission while using a single side band

and the carrier.

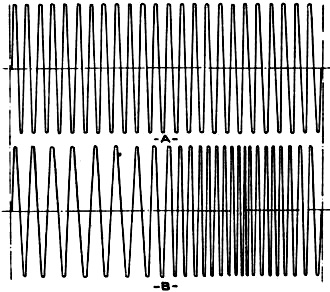

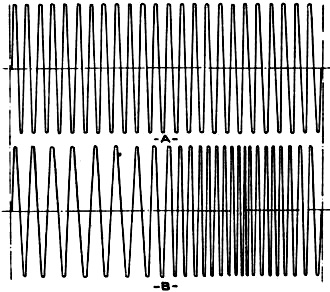

Fig. 2 - Compare frequency modulation with amplitude modulation

shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 3 - A simplified circuit for achieving frequency modulation;

the practical method is much more complex.

Frequency Modulation

However, in frequency modulation (which is the basis of Major Armstrong's new

system of transmission, described in the August 1935 issue of Radio-Craft, on page

75) the amplitude and the phase do not vary; the frequency is the only variable

element. If the frequency of the unmodulated current is fo, the modulated frequency

varies for a given amplitude of the audio signal between fo + f and fo - f; (f is

the frequency variation). For instance, a frequency-modulated 1,000,000-cycle carrier

for a given audio amplitude may have a variation f = 1,000 cycles, which means that

while the audio signal varies during the cycle, the frequency of the carrier will

vary between 1,001,000 cycles and 999,000 cycles. For a larger audio amplitude,

the variation may be 2,000 cycles and the variation range therefore 1,002,000 and

998,000. If f1 is the maximum frequency variation which may be caused

by the maximum audio amplitude, any instantaneous frequency value of the frequency-modulated

carrier lies between fo + f1 and fo - f1. Frequency modulation

is shown graphically at A and B in Fig. 2. It will be noted that the amplitude

of the modulated wave (B) is the same as the carrier (A).

There are several elements in an oscillator, the variation of which may cause

a change in the frequency of the generated current. However, the most convenient

method for producing a pure frequency modulation is to act either on the capacity

or on the inductance of the oscillatory circuit - preferably on the capacity. Figure

3 shows a simple set-up for frequency modulation using capacity variation. In parallel

to condenser C of the oscillatory circuit is connected a modulating condenser MC

which is either a condenser microphone or a Baldwin headphone rebuilt for this purpose.

The latter - is easily constructed as follows.

The mica diaphragm is covered with thin aluminum foil, electrically connected

to one end of C. A heavy, insulated metal plate is fixed in front of the diaphragm

and is connected to the other end of C. The modulating frequency is supplied in

this case by the audio amplifier. With such an arrangement a sound of a given frequency

and amplitude will cause a sinusoidal variation of the part f.

If the frequency variation f is small with comparison to fo, the ratio of the

capacity change C1 to the total capacity Co is twice f. For instance, if Co = 250

mmf.; fo = 1,000,000, and we wish to have a maximum variation of 2,000 cycles; f

is equal to 2,000. The ratio

Thus a variation of 1 mmf. in the capacity of the modulating condenser will produce

a change of 2,000 cycles in the frequency of the generator. A mathematical analysis

of frequency modulation, and carefully conducted experiments prove that a current

modulated in the manner just described can be considered as consisting of an unmodulated

carrier and an infinite number of sidebands. The sidebands are in pairs and their

respective frequencies are: fo + p, fo -- p, fo + 2p, fo - 2p, fo + 3p, fo - 3p,

etc. Where fo is the frequency of the carrier and p the modulating frequency. the

amplitudes of the carrier and the sidebands depend upon a certain factor mf called

the "modulation index." The modulation index mf is equal to a certain constant K

multiplied by the ratio of the two frequencies

mf = (K1fo.) / P

We see that the amplitudes of carrier and sidebands depend upon the modulating

frequency. While the amplitudes in each pair of sidebands in amplitude modulation

are equal, the sidebands in frequency modulation generally differ. When the modulating

index mf is small the amplitudes of the sidebands above the second are negligible

and may be neglected. However, when mf increases, the importance of the higher sidebands

becomes more noticeable.

An "aperiodic" detector cannot produce an audio signal from a frequency-modulated

current. The frequency-modulated signal must be converted into one which is amplitude-modulated

in order to he made audible.

This can be done by inserting a tuned circuit between the antenna and the detector,

or by using filter systems. This means that practically any receiver with very sharp

tuning can receive frequency modulated signals. The quality is another question;

and in Armstrong's system, a special network of current limiting and filter circuits

are used to maintain a high-quality output.

Phase Modulation

A mathematical analysis of phase modulation shows that similarly to frequency

modulation the modulated current can be considered as consisting of an unmodulated

carrier and an infinite number of pairs of sidebands. Using fo as the carrier frequency

and p as the modulating frequency, the frequencies of the sidebands are: fo + p

and fo - p; fo + 2p and fo -- 2p; fo + 3p, and fo - 3p, etc. The amplitudes of the

carrier and the sidebands are a function of the modulating index mp (mp = K1fo)

which unlike frequency modulation is independent of the modulating frequency. Here

again when the modulating index is small, in other words when the maximum shift

of the phase angle is small the bands above the second have practically no influence.

An aperiodic detector cannot rectify a phase modulated wave (similar in this

respect to frequency modulation). The transmitted wave has to be amplitude modulated

before it reaches the detector. This is accomplished by inserting a tuned circuit

between the antenna and the receiver or by using a filter system in the same position

in the circuit. From the above consideration we may easily come to the conclusion

that neither frequency nor phase modulation narrow the band width. As a matter of

fact it appears that only under ideal conditions is the band width of the latter

two systems equal to that in amplitude modulation, though it is true that in short

waves the problem of band width is less acute than in the broadcast range. Very

little can be said about the practical merits and defects of the latter two systems

of modulation, as experimental data are quite limited.

Posted October 18, 2023

(updated from original

post on 8/12/2016)

|