|

December 1952 QST

Table of Contents Table of Contents

Wax nostalgic about and learn from the history of early electronics. See articles

from

QST, published December 1915 - present (visit ARRL

for info). All copyrights hereby acknowledged.

|

Here's a topic - power supply filter

design - that never goes out of

style. It was originally published in a 1952 issue of QST magazine. Without

bothering to worry about source and load impedances, this brief tutorial on the

fundamentals of power supply filter design using series inductors and parallel capacitor

combinations. Author Gabriel Rumble offers a rule-of-thumb type formula for guessing

at a good inductor value based on peak-to-average expected current. This is by no

means a comprehensive primer on power supply filter design and is directed more

toward someone new to the concept of removing or reducing noise and AC ripple

from the output of a DC power supply.

PowerSupply Filters - Fundamental Facts for the Beginner

By Gabriel P. Rumble, EX-W5BBB

If the requirement is pure (that is, unvarying) direct current, the rectifier

outputs shown in a previous article1 will not fill the bill.

We must use the properties of L and C (or sometimes R and C) to iron out the

ripples in the rectified current.

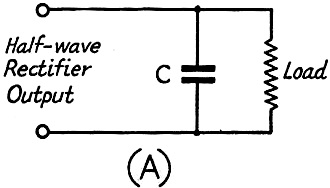

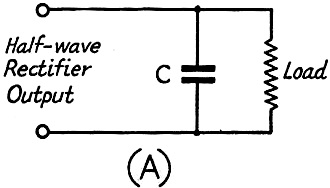

If a condenser is placed in parallel with the load on a half-wave rectifier,

as shown in Fig. 1A, the voltage between alternations does not drop to zero,

because the condenser charges during the conducting half-cycle and discharges through

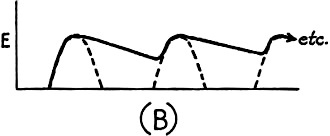

the load during the nonconducting half of the cycle, as shown in Fig. 1B.

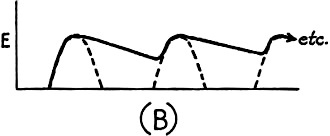

Fig. 1 - The discharge of a condenser connected across the

load resistance helps to smooth out the bumps in the output of the rectifier.

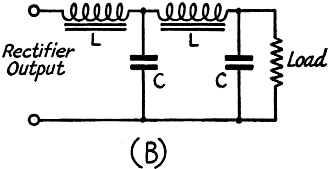

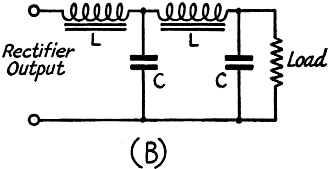

Fig. 2 - A choke in series with the load provides further

smoothing. If additional filtering is required, a second filter section may be added.

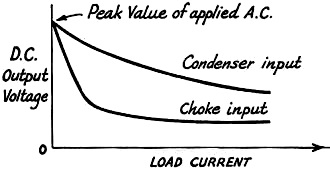

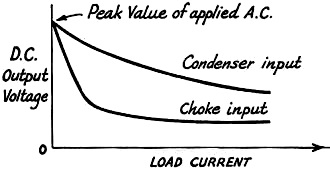

Fig. 3 - Comparison of the voltage regulation with condenser-

and choke-input filters.

A comparison of the output waveforms shown previously should make it clear why

the output of a full-wave rectifier is easier to filter than that of a half-wave

rectifier. In either case, the condenser will by-pass some of the ripple around

the load. The greater the capacitance, the slower the RC decay and the shallower

the ripple.

The action of a condenser in a filter circuit is analogous to that of shock-absorber

springs in a wagon traveling over a cobblestone road. We can further smooth out

the ride by adding weight to the wagon. This step is comparable to the addition

of a choke (inductance) to the filter circuit, as shown in Fig. 2A. The elasticity

of the condenser and the inertia of the inductor are being utilized to smooth out

the ripples that would otherwise exists across the load. Further filtering and the

consequent approach to pure direct current may be accomplished by additional sections

of filter, as shown in Fig. 2B. (Suggestion: Consult your favorite textbook

on the interesting subjects of resonant filters and swinging chokes.)

If the full rectifier output voltage is applied to the condenser, as shown in

Fig. 2A, the filter is said to be of the condenser-input type. If, instead,

the ripple voltage first undergoes an IXL drop before being applied to

the condenser, as illustrated in Fig. 2B, the filter has choke input. (Suggestion:

Look up the subject of critical inductance.)

A comparison of the voltage regulation of supplies having condenser and choke

input is shown in Fig. 3 (p. 130). With condenser input, the output voltage

varies considerably with varying loads. With choke input, the output is almost constant

for a wide range of load variation. The variation occurring in this flat range is

caused by the d.c. resistance of the choke and rectifier resistances and the leakage

reactance of the transformer. However, in well-designed components these are usually

quite low. The load current at which the knee of the curve occurs is dependent on

the inductance of the input choke. The greater the inductance, the smaller the value

of load current at which the curve starts to flatten out.

In addition to providing a flatter characteristic, the use of choke input has

another advantage. It reduces the ratio of peak to average current passed by the

rectifier. If it were desired to design a rectifier for a fixed load current of

I amperes and E volts, and if it were further desired that the peak rectifier current

should exceed the average by only P%, then the inductance, L, in henrys, of the

input choke, should be

L = E / (10*P*I), where:

L is inductance in Henries

E is peak voltage

I is peak current

P is peak-to-average current ratio

The knee of the characteristic will occur at a current of P*I amperes. If it

were desired to have the knee at a lower current, a smaller value of P would be

selected and a higher L would be called for. Where good regulation down to low values

of load current is not of interest, and the values of full-load current and rectifier

current rating permit, the values of P above 5 per cent will usually be more economical.

Filter chokes are usually placed in the ungrounded side of the rectifier output.

If the choke is placed in series with the transformer and ground, the capacitance

of the secondary winding of the transformer to grounds tends to by-pass the choke.

If the expected current drain on a rectifier is very slight, resistors, which

are comparatively inexpensive, may be used in place of the chokes. A 1000-ohm resistor,

for example, will do just as much filtering as 1000 ohms of inductive reactance

at any given ripple frequency. It should be stressed that this is practical only

when the load resistance is much higher than the filtering resistance. Also, the

d.c. voltage drop in the filter resistor and its adverse effect on regulation must

be taken into account.

1 Rumble, "How Rectifiers Work," QST, October, 1952, p.42.

Posted June 30, 2022

(updated from original post on

4/14/2016)

|