|

May 1953 QST

Table of Contents Table of Contents

Wax nostalgic about and learn from the history of early electronics. See articles

from

QST, published December 1915 - present (visit ARRL

for info). All copyrights hereby acknowledged.

|

Maybe I suffer from cranial rectumitis at

the moment, but I'm having a hard time with a statement made in this 1953 issue

of QST magazine about coaxial feedline

impedance, to wit, "102-ohm line (52-ohm lines in series)." I must be missing something

because I don't understand how placing two 52-ohm transmission cables in series

results in twice the impedance. Aside from that, author John Avery presents an interesting

article on multi-impedance dipole antennas. Empirical data is presented on how the feed-point impedance of a dipole varies with distance above the ground. His results

are very close to theoretical values which assumes non-sagging elements, perfectly

linear alignment, a perfectly conductive ground, etc. He then extended his investigation

into 2-wire (4x impedance) and 3-wire (9x impedance) folded dipole antennas.

Multi-Impedance Dipoles

Closer Matching at Various Antenna Heights

By John D. Avery,* W1IYI

While looking at a chart in the ARRL Handbook that shows the impedance of a half-wave

antenna at various heights above ground, I began to wonder if a wire at my QTH would

behave "like the book says." My location is at a lake shore, where water and wet

ground are always present, so any measurements could be made over a period of time

without running the possibility of a significant change in the electrical ground.

("Electrical" ground and the "surface" ground do not coincide - the electrical ground

is usually some feet below the surface, depending upon the characteristics of the

soil and the radio frequency being used.)

Fig. 1 - The solid line is a theoretical curve showing the

variation in impedance for a single-wire half-wave antenna at various heights above

ground. The values for 2- and 3-wire folded dipoles can be expected to vary in the

same way. The small circles are experimentally-determined values for a single-wire

antenna.

Fig. 2 - With three wires strung up in the air, one has

the choice of connecting them as (A) plain dipole, (B) 2·wire folded dipole, and

(C) 3-wire folded dipole.

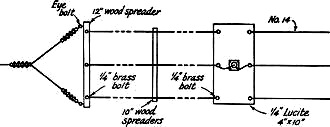

Fig. 3 - Constructional details of the multi-impedance antenna.

Pine spreaders are used, boiled in paraffin to make them water-resistant. The antenna

wires (and jumpers) are connected to 1/4 inch brass screws in the end spacers and

in the Lucite terminal block. The terminal block carries a coax fitting - an open-wire

line can be connected directly to the brass screws.

The measurements were made with a single wire a half wavelength long, split in

the center so that a 52- or 72-ohm coaxial line could be connected. Two 60-foot

towers were used to support the antenna, and a standing-wave bridge was available

for use in the coaxial line. The procedure that was followed was quite elementary

- with a given coaxial line connected to the antenna, the antenna was raised a few

feet at a time until the minimum s.w.r. was indicated.

Starting with 52-ohm coax and the antenna, one foot off the ground, the s.w.r.

was rather high, but as the antenna was raised the s.w.r. dropped and was quite

close to unity at around 35 or 40 feet. Substituting 72-ohm coax for the lower-impedance

line, the s.w.r. was higher. As the antenna was raised (now fed with 72-ohm line)

the s.w.r. was dropping as the maximum height of 60 feet was reached.

It is safe to say that practically everyone ignores the effect of "height above

ground" on the impedance of an antenna. This doesn't make any practical difference

in many cases, but it can where you use a "flat" line and no means for adjusting

the match. This article tells how W1IYI didn't ignore the height factor, and how

it led to some interesting results and a slightly different concept in antenna design.

Having run out of height at my place, I managed to prevail upon a ham in Rhode

Island who had higher supports to test with a 102-ohm line (52-ohm lines in series),

and he found the minimum s.w.r. to fall at around 90 feet.

The diagram in Fig. 1 shows part of the Handbook graph that started this

whole thing, with the three experimentally-determined points shown as small circles.

Since they don't fall too far off the curve, they seem to prove that "the book is

right."

This got me thinking about what might be happening to folded dipoles at various

heights above ground. Since a two-wire folded dipole shows a four-times step-up

in impedance (and a three-wire dipole a nine-times step-up) I added these values

to the chart, on the left-hand side. A little study of this chart shows that, for

low antenna heights (low in wavelengths) such as one runs into on 75 meters, the

first choice of antenna and feed line might not always be the best. For example,

a two-wire dipole only 25 feet off the ground should match better with 72-ohm coaxial

line than with 300-ohm ribbon. A 3-wire dipole 35 feet above the ground offers a

better match for 300-ohm line than does the more conventional 2-wire folded dipole.

These statements are based on "electrical" ground, of course, a somewhat variable

plane in most cases. Nine times out of ten it can only be found by experiment.

The Multi-Impedance Dipole

In an attempt to make better use of this (to me) newfound knowledge, a simple

spreader system was devised that would permit changing quickly between two- and

three-wire folded dipoles and a single-wire dipole. As shown in Fig. 2, the

basic three wires can be used in these three ways. The spreaders were made from

soft pine turned down to size and then boiled in hot paraffin. Fig. 3 shows

some of the construction details. A center connecting block of 1/4 inch Lucite was

built to take terminals and a coaxial connector, for quick changing of the various

feed lines. It is apparent from Fig. 2 that changing from one antenna to another

only requires changing a few jumpers, and perhaps disconnecting one feed line and

connecting another.

With a system like this, it is not too difficult a task to find the best combination

of line and antenna for the particular height you have available. You will probably

want to use the maximum available height for the antenna, so it isn't suggested

that you run the antenna up and down for a perfect match, although you may find

the experiment interesting, as I did. For any length of antenna there is one frequency

at which the s.w.r. is a minimum, and the s.w.r. will increase slowly as the frequency

is changed in either direction. However, I noticed that the 2- and 3-wire folded

dipoles, and the 3-wire dipole of Fig. 2A, seemed to be "broad" in this respect

and not at all critical.

Although it has been pointed out many times before, it is worth repeating here

that you need suitable coupling at the transmitter for each type of line. If you

use an antenna coupler, small 2- or 3-turn links are adequate for coupling between

coupler and transmitter, but larger links may be required if no coupler is used.

I use plug-in links and a variable condenser in series with one side of the line.

The largest plug-in link is 12 turns.

Right now I am using the antenna of Fig. 2A, fed with 52-ohm coaxial line.

Local and DX results on 75 have been very encouraging.

This is all that is required for a 20-meter antenna in which several different

values of impedance can be obtained. An antenna for a lower-frequency band would

require only more wire and more intermediate spacers.

Posted April 15, 2022

(updated from original post on 4/28/2016)

|