December 1966 QST

Table

of Contents Table

of Contents

Wax nostalgic about and learn from the history of early electronics. See articles

from

QST, published December 1915 - present (visit ARRL

for info). All copyrights hereby acknowledged.

|

When it comes to low loss transmission

media, it's hard to beat waveguide and open wire. Open wire can exhibit less a couple

tenths of a decibel per hundred feet at low frequencies, but it is very susceptible

to perturbations from nearby objects, wind and moisture. Waveguide exhibits a few

tenths of a decibel per 100 feet at very high frequencies, but it is expensive and

difficult to work with. In the middle is coaxial cable, which for a good quality

product of appropriate size, you can get very low attenuation. As with most things,

you get what you pay for in coax cable. I once used really expensive Andrew (now

Commscope)

Heliax coax cable on an S-band radar (2.8 GHz) system that had only

a little more than 1 dB/100 ft, which was necessary from a receiver noise

figure requirement rather than for transmitter power efficiency. This article from

QST covers some of the basics of low loss cable.

Low-Loss Coax

Reduced Attenuation Through Improvements in Construction

By Freeman F. Desmond and Richard Tuttle (W1QMR)

c/o Times Wire & Cable, Wallingford, Conn.

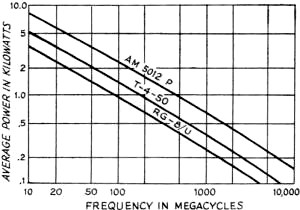

Fig. 1 - Relative loss distribution in coaxial cable as

a function of frequency.

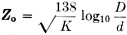

Fig. 2 - Attenuation in decibels per 100 feet of cable vs.

frequency.

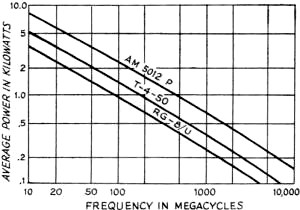

Fig. 3 - Power-handling capacity as a function of frequency.

RG-8A/U coaxial cross-section.

T-4-50 coaxial cross-section.

1/2-inch Alumifoam (AM5012P) coaxial cross-section.

RG-17A/U coaxial cross-section.

Fig. 4 - Cross sections showing construction of various

types of cable.

Fig. 5 - Representative cable installation for a rotary

beam antenna.

1) Transmitter.

2) Transmitter output connector.

3) Flexible 50-ohm coax

(T-4-50 or RG-8A/U).

4) Type N connectors or flexible-cable to solid-sheath splice.

5) Solid-sheath foamed-dielectric cable (1/2-inch Alumifoam).

6) Type N connectors

or flexible-cable to solid-sheath splice.

7) Flexible coax (T-4-50 or RG-8A/U).

8) Cable clamps.

9) Tower.

10) Rotator.

We have all used RG-8/U or similar cables for radio-frequency transmission. Very

often we have wished for a cable with lower losses and improved power-handling capability

- one that is also relatively easy to install and reasonable in cost. Such a cable,

with compatible connectors, has been designed and is now available.

To see how this improvement is accomplished, we should first look closely at

various coaxial constructions and examine the factors which cause losses. The ideal

coaxial cable - an inner conductor suspended, by air alone, concentrically inside

an outer conductor - is for all practical purposes impossible; actual coaxial cable

must be manufactured with supporting material or dielectric between the two conductors.

The loss in percent of total contributed by each of the cable components may be

seen in Fig. 1.

At 100 Mc. approximately 80 percent of the total loss is copper loss in the center

conductor. At lower frequencies this percentage contribution to loss is even greater.

Therefore, the center conductor is the most important factor to consider in reducing

cable losses in a given frequency band.

The Center Conductor

It would be most desirable, to achieve lower attenuation, to increase the size

of the center conductor. We do not, however, wish to change the characteristic impedance

nor contribute substantially to size or weight of the cable. Since impedance is

dependent upon the geometry of the cable,

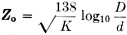

where Zo = Characteristic impedance

K = Dielectric constant

D = Dielectric diameter

d = Center conductor

diameter

merely increasing the size of the center conductor would change either the characteristic

impedance or add substantially to the overall size and weight of the cable, neither

of which is desirable. The dielectric constant is the area that we can change, if

a material of lower dielectric constant can be used practically.

Solid polyethylene (dielectric constant K = 2.3) is the dielectric material of

most coaxial cables. By changing to foamed polyethylene (K = 1.5) we may increase

the center conductor size and lower the attenuation without changing the overall

diameter or the impedance. In this dielectric minute air bubbles are encapsulated

in the polyethylene during manufacture. Incorporating air bubbles brings the finished

product closer to the dielectric constant of air (1.0), which is the goal, and achieves

the lowest attenuation characteristic. With cellular polyethylene, costly pressurization

of the cable is not necessary, as it is in the case of disk-supported, helical-supported,

or spline-supported semiflexible coaxial cables.

Figs. 2 and 3 show the attenuation and power capacity vs. frequency of RG-8A/U,

Times T-4-50 and Times 1/2-inch Alumifoam. The lower attenuation is evident in the

latter two because of increased size of center conductor and changed dielectric

constant.1

Fig. 2 also illustrates another point: When a stranded center conductor

is used instead of a solid, smooth, center conductor the spiraling of the stranding

results in a spiraling of the r.f. current along the conductor, creating a longer

r.f. path length. Coupled with the higher resistivity of the center conductor because

of the contact resistance between the strands, this contributes to higher attenuation

in the finished cable. RG-8A/U has a stranded copper center conductor, while T-4-50

and 1/2-inch Alumifoam have solid-copper center conductors.

Jacket Material

Another factor which may affect attenuation is the jacketing material of the

cable. Most flexible coaxial cables use polyvinylchloride (p.v.c.) as the jacketing

compound. However, to use p.v.c. - a relatively hard, brittle substance - it is

necessary to add plasticizers to make the compound pliable and flexible. The nonresinous

plasticizers compounded with p.v.c. have a tendency, with sunlight and summer temperatures,

to leach out of the p.v.c. and migrate into the polyethylene of the dielectric.

The migration of the plasticizer through the braid into the dielectric causes the

dielectric constant and power factor to rise, with a resulting rise in the v.s.w.r.

and an increase in attenuation. A rise in attenuation of 1 or 2 db. per 100 feet

is not uncommon, once contamination has begun. Also, with the migration of the plasticizer

the p.v.c. becomes brittle and nonpliable, resulting in cracking and breaking of

the jacket. RG-8/U, RG-11/U and RG-17/U are examples of coax cables with contaminating

p.v.c. jackets.

The path between transmitter and antenna can be a lossy one, especially at v.h.f.

and u.h.f. Every decibel lost subtracts from antenna gain or transmitter output,

so why lose any more than is absolutely necessary? Here's a look at the characteristics

and application of some of the newer cables.

The dangers of this condition have been recognized, and in many of the military

cables, identical in every respect except for jacket material, the older styles

have been replaced by new ones. Cables such as RG-8A/U, RG-11A/U, and RG-17 A/U

use p.v.c. jackets with a resinous plasticizer which does not leach out or migrate,

and thus does not contaminate the dielectric. Life expectancy of this type jacket

is in excess of fifteen years.

High-molecular-weight, carbon-black-loaded, polyethylene jackets such as Xelon

contain no plasticizers of any kind, consequently a useful life of 25 years or more

can be expected. Because of this, polyethylene jackets permit direct burial and

are usually specified for submersible applications.

Impedance Uniformity

Attenuation is also increased by substantial v.s.w.r. Since v.s.w.r. is a function

of the impedance of a cable, it follows that the more uniform the impedance the

lower will be the v.s.w.r. (for a given termination). Because coaxial cable is manufactured

of plastic materials by means of bulky extruders, it cannot be held to the tolerances

of machined parts, especially in lengths of many hundreds of feet. Each individual

extruder has its own peculiar eccentricities that cause variations in the cable

during manufacture.

These variations in dimensions are very small but, unfortunately, sum up electrically

along a length of cable and, at specific frequencies, may result in a v.s.w.r. as

high as 4:1 even though the cable is properly terminated. In cable constructions

where impedance uniformity and low v.s.w.r. are critical, the impedance can be held

to tight tolerances by close control of the extrusion processes.

Cable Construction

Taking the foregoing into account, let us look at RG-8A/U, shown in cross-section

in Fig. 4. The center conductor is stranded copper and the dielectric is solid

polyethylene. The attenuation of RG-8A/U could be improved by 25 percent if we could

increase the center conductor size and change to foamed polyethylene. This has been

done in cable such as Times T-4-50, now available at about the same cost as RG-8A/U.

Note that the overall diameter is the same, Fig. 4, but the attenuation is

substantially improved (Fig. 2) and the cable weight is improved (99 lbs./1000

ft. for RG-8A/U, 94 lbs./1000 ft. for T-4-50).

However, for longest life and most carefree installation, even further improvements

have been made. The largest factor contributing to degradation of attenuation in

foamed polyethylene flexible coaxial cables, especially above 100 Mc., is moisture.

Since moisture affects the power factor, the effect of moisture in the cable becomes

significant as we increase frequency. This can be seen from the formula for attenuation:

where,

As frequency is increased, the power factor becomes a more significant figure.

Moisture has been known to degrade the power factor by as much as ten times.

But how does moisture get into a cable? It enters flexible cables as water vapor,

which is a very penetrating gas. This vapor condenses to water or moisture, changes

the power factor and consequently raises the attenuation. For this reason, a solid,

seamless, pinhole-free, metallic barrier or shield which positively excludes water

vapor gives the longest-lived cable. In addition, with a solid metallic sheath the

radiation into and out from the cable is eliminated, and isolation the order of

100 db. is achieved.

In cables such as the Times Alumifoam series moisture is precluded during manufacture

by a completely dry core, and with the addition of the aluminum tube the foamed

polyethylene is under constant pressure. Moisture traps and vapor paths are designed

out, and the user has a self-sealing cable.

For above-ground applications, the seamless shield serves the dual function of

electrical shield and protective cover. It eliminates the necessity for an outer

jacket and thus represents the most economical use of weight and space to achieve

desired electrical characteristics. To approximate the electrical characteristics

of 1/2-inch Alumifoam in an RG cable, it would be necessary to use RG-17A/U (attenuation,

0.85 db. at 100 Mc.; power handling, 3.6 kw. at 100 Mc.: cost, approximately 30

percent higher). Cross sections of the two types are shown in Fig. 4.

System Installation Using Semiflexible Coaxial Cable

Fig. 5 illustrates a typical system installation employing 1/2-inch Alumifoam.

The cable is simple to install, and connectors are readily available for it.

It is generally most convenient to run from the transmitter to the wall of the

shack with flexible coax (RG-8A/U or T-4-50), although to eliminate losses, this

run should be kept as short as possible. One end of this short run should be terminated

in a connector that will mate with the transmitter, and the other end may terminate

either in a type N or go directly into a splice connector. Splice connectors to

accept flexible coax in one side and solid-sheath coax in the other are also available.

The main feeder run should be cable similar to 1/2-inch Alumifoam because of

its low-loss characteristics. Since the cable is designed to be bent upon installation,

there is no electrical or physical damage in bending it, even on a radius as small

as ten times the o.d. of the cable. The cable should be terminated to match with

the transmitter cable connector (type N or splice). The type N connector is better

than the PL-259 because of its lower v.s.w.r., greater power-handling capability

and improved radiation characteristics. For still lower system v.s.w.r., the conversion

splice is the wiser choice.

The antenna end of the main feed line should be terminated by the same procedure

as the transmitter end. Jumping from the solid-sheath cable to the antenna is accomplished

by means of a short length of RG-8A/U or T-4-50. The cable loops once around the

rotator and is terminated as you now terminate in your antenna.

In conclusion, solid-aluminum-sheath cable can be reasonably expected to deliver

more power to the antenna because of its low v.s.w.r. and lower attenuation characteristics.

Combining solid-sheathed, foamed-polyethylene dielectric, aluminum-shielded coaxial

cable and low-v.s.w.r. connectors gives a feeder connecting system which, at v.h.f.

and u.h.f., may deliver as much as 70 per cent more power from transmitter to antenna

in a comparatively short run.

1 T-4-50 is a flexible cable with foamed dielectric and braid outer

conductor; Alumifoam is similar but uses seamless aluminum tubing as the outer conductor.

Both are made by Times Wire & Cable Div., International Silver Co., 358 Hall

Ave., Wallingford, Conn. 06492. -- Editor.

Posted April 7, 2020

(updated from original post on 3/15/2013)

|