|

April 1946 QST

Table of Contents Table of Contents

Wax nostalgic about and learn from the history of early electronics. See articles

from

QST, published December 1915 - present (visit ARRL

for info). All copyrights hereby acknowledged.

|

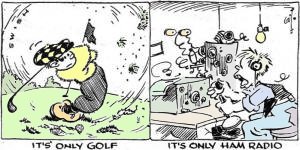

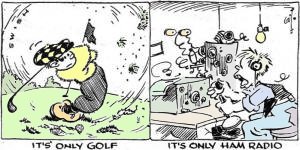

The more things change, the more they stay

the same. That saying applies to many recreational activities. Pick up a copy of

the ARRL's QST magazine that was published in the last year and look at

reader comments and you will find laments about the dwindling participation of youngsters,

an increased degree of incivility and rule breaking during engagement, the high

cost of getting into the hobby, yadda yadda yadda. I witness it regularly in the

model aircraft world, too. That is not to say the issues are not true or irrelevant,

just that they are persistent. Each generation, it has been said, tends to think

of history beginning when he/she was born and all situations are new to his/her

generation. Those of us who have lived through more than a single generation have

seen the cycles repeat. They will continue to repeat. I am of the opinion that overall

things improve by virtue of natural selection from a technical perspective. My proof

is the undeniable advancement of the state of the art in both equipment and operators.

Good Operating Pays Off

Hints for Beginner and Old Timer Alike Hints for Beginner and Old Timer Alike

By John Huntoon* W1LVQ

Most of us have had the unhappy experience, when firing up the rig after four

years of idleness, of finding a bleeder that opened, a by-pass that let go, or a

strange new parasitic in the final. A few minutes with the Handbook, a screwdriver

and the junk box usually fixes the trouble.

Many of us have likewise found our operating has suffered wartime casualties

- Are we putting enough dahs in the numeral" 1 " or are we sending WJLVQ? ... Is

the portable designator "BT" or the fraction bar? ... Are we making long enough

calls? And the like.

We get straightened out somehow. But most of us find our answers haphazardly,

such as imitating the procedure used by another operator -who may or may not know

what he is doing. After we have been back on a while our operating again becomes

more or less automatic - fine if the habits are good ones, deplorable if they are

not. This business of imitating the other fellow is the way most of us acquire our

operating habits, which are formed early and last long. For less interference, for

better relations with fellow operators, for more accomplishment with one's station

- in short, for a better enjoyment of amateur radio - these habits must be good.

We often tear down our rigs, on paper at least, to examine the possibility of rebuilding

a more effective unit. Isn't the same procedure applicable to our operating habits?

And isn't right now an ideal time to review them?

Fig. 1 - Customary toning practices, depending on location

in the amateur band.

About now we can hear some gent switching off his rig and pleading, "Aw, let

us alone - after all, it's only ham radio." Sure it is. You can also hack around

18 holes of a golf course, driving into the foursome ahead, forgetting to replace

divots, defacing the green with practice swings that go astray - if you want to

have that kind of fun.

Sure, it s only golf. But the golf club and its members won't want you, and neither

does ham radio need or want the sloppy and inconsiderate operator. Some fellows

with the snappiest-looking stations and strongest signals would be surprised to

know what brother hams actually think of their operating habits.

So, when you sit down at the rig tonight, whether you are a bearded old-timer

with thousands of QSOs behind you or an LSPH with a brand-new station license ready

for your first contact, give some thought to this business of operating .

The most important fundamental is that a good amateur operator spends much more

time listening than transmitting; otherwise he becomes a pseudo "broadcaster." The

good op knows he gets more results by thorough listening. He has the "feel" of the

band; he knows what is going on. He thereby avoids useless calls and QRM to others

- and incidentally saves on the electric bill. You won't hear him rabidly calling

CQ DX while some choice foreign stuff is trying to work through on his own frequency

- a fault of which many of us have been guilty. Let's leave the key or mike alone,

then, until we find out - by listening - what's going on in the band we choose for

the evening's work.

There are two ways we can attempt contact: call another station or send the general

CQ. The smart amateur, if he wants a really pleasant contact, first searches the

general territory surrounding his chosen transmitter frequency, since on the major

ham bands it is accepted practice to work only such a portion of the band; he selects

a station with a clean signal and, if on c. w., a good "fist" and a code speed about

like his own.

How long to call? For an accurate answer you must be familiar with practices

in the particular band, but some generalizations may be made: If operating near

(for c.w., within about 75 kc. of) the edge of the band, and calling a station in

the same tuning area, you should call the approximate length of time necessary for

the CQer to tune from the edge to your frequency, as in Fig. 1A. You may approximate

this time by several "test" receiver runs of your own, tuning between the band edge

and your transmitter frequency. It is obvious that in a crowded band a slightly

longer call will be necessary, as more time will be required for the searching party

to examine the additional signals as he tunes through them towards you. It is also

obvious that if your station is right near the band edge, you may need to call only

four or five times before signing. This sounds like a neat operating convenience,

but in practice a tendency to crowd the edges of the bands results in a higher QRM

level and less chance of being heard when one calls.

Fig. 2 - Excessive signing during a CQ decreases its effectiveness,

as shown in B.

When operating away from band ends, a CQer will usually listen for answers in

the general vicinity of his own transmitter frequency, plus or minus 50 or 100 kc.

The calling time is more difficult to estimate here, since it is usually not known

whether the CQer will first tune towards your frequency, or away from it and return

later, as in Fig. 1B. Actually it is logical to plan two calls here: a fairly

short one with a quick (but clean) sign-off, assuming the CQer is tuning toward

you - and, if no answer comes, a second short call on the assumption the CQer tuned

the other way first and, having reversed his dial motion, is now tuning toward you.

Actually, the ultimate in calling convenience and efficiency is the use of "break-in."

At the very least a well-designed station has a control scheme which will allow

rapid changeover between receiving and sending status. For 'phone work the most

common arrangement is "push-to-talk," where one push-button control cuts off the

receiver and turns on the transmitter, as well as operating an antenna switching

relay if that is necessary. Such an arrangement permits the calling station to interrupt

his transmission momentarily and check on the called station. He may, by saying

"break" as he cuts his carrier, invite the called station to respond immediately;

by a several-second check of the channel he may determine whether (1) the called

station has answered some one else, in which case of course he ceases further calling;

(2) there is no indication that the called station has returned, in which case he

continues his call; or, as he hopes, (3) the called station answers him.

In c.w. work this may be carried one step further, if a separate receiving antenna

is used and the transmitter oscillator stage is keyed. The receiver may be left

on while calling (with headphones not clamped too tightly over the ears!) and thus

the operator may have a constant check on the channel of the called station by what

he hears during the minute periods the key is up between words and even between

characters. Not so much as a dit need be wasted with such a system. It is helpful,

also, as a constant check on communication during a QSO, particularly in message-handling

work.

Regarding calling procedure for c.w., present recommendations are something like

five calls and two signatures, the whole repeated several times. Actually there

is no point to signing in the middle of a call; if the CQer happens to tune through

your signal at the moment you are signing, he'll never know you're calling him.

If not using break-in, then, before signing make calls a sufficient length to ensure

the CQer a chance to reach your frequency during his tuning process; then sign clearly.

Remember that while your call letters are quite familiar to you, they're probably

new to the other guy - so watch your enunciation and phonetics, or "fist" if on

c.w., when signing your call.

Calling practices.

If you want to take "pot luck" and talk to anyone, a CQ is the thing. If interested

in a particular direction or locality, possibly for purposes of message relay, so

indicate in your call; e.g., "CQ WEST," "CQ W8," or "CQ CHGO." When sending a CQ

make its length sufficient to accomplish the result of attracting one or more operators,

yet short enough not to cause the listening op to tire of waiting for you to finish.

Much will depend on the amount of activity in the band; a crowded band indicates

many more operators are tuning for CQs so but a short transmission is needed. It

is well to point out here that there is little use in signing at length during portions

of a CQ. Compare A and B of Fig. 2. The brackets show the effective portions

of the transmission - an operator's attention will not be attracted if he tunes

through your signal while you are signing (except in an otherwise empty band - if

such a thing exists). While the B transmission is somewhat longer, A is actually

more effective. Care should be taken not to send too many CQs without an intervening

signature, however; 8 or 10 is the maximum. While our examples have been mostly

in c.w. terms, the principles apply also to 'phone work.

We're talking about operating now, and it is assumed your transmitter is properly

adjusted to put out a clean signal free from chirps or keying transients or, in

'phone work, with no splatter nor appreciable distortion. These factors are particularly

important in CQs. If you can operate from Nyasaland and sign a ZD6 prefix you'll

get answers no matter what kind of r.f. your rig emits; but so long as you sign

a common prefix such as W or VE, brother, your replies will be generally in proportion

to the quality of your signal.

After establishing contact, what? Well, that's pretty much up to you as an individual.

For goodness' sake, be one! Don't fall into the dull routine of a stereotyped contact

just because many others do. Our preachments so far have related to the business

of establishing communication on an orderly basis; we must all practice a common

calling procedure to facilitate contacts. But once in a QSO, it's up to you to forget

your secondary status as a bug-pusher or mike-holder and become an individual.

The gent you work will want a signal report - if it is honest - and your location.

Those are probably the only two standard items of useful conversation. If the weather

isn't unusual, why bore him with it? A routine description of a routine rig is dull.

But if you're using a new antenna feed system or a modulator that cuts off the "highs,"

that's something new! Talk about the same things you might if the fellow were right

in your shack. In fact, if you want the greatest return from your operating time

it is smart policy to make occasional schedules, especially when you find a good

operator; thus you can make friends and get away from stereotyped contacts which

exchange routine information of little interest to either participant. We c.w. operators,

generally speaking, observe much better calling and working procedures than our

'phone brothers, but are apt to be a bit routine in the body of our QSOs - yet the

conversation is the object in making contact! We 'phone gents, conversely, are often

sloppy about communications procedures but, except in instances where we overdo

the business of being an individual, usually have more personalized QSOs. Each group

can learn much from the other.

The smart 'phone amateur steers clear of

inane conversation, for he knows he is "the voice of amateur radio in the loudspeakers

of the world." He has no silly phonetic identification such as, "Double-you One

Little Vicious QRMer," for he knows the boys will laugh at him, not with him. He

does not believe in the false modesty of an editorial "we" if his is a one-operator

station. Neither does he use the trite, "The handle here is Joe"; if his name is

Joe, he says so. He does not chide his wife for listening to the morning radio serials

or "soap operas" and then give the same sort of performance during his ham contacts.

Yes, we previously said, "Be an individual." There's a difference between being

an individual and being a screwball. The point is in how we conduct our contacts. The smart 'phone amateur steers clear of

inane conversation, for he knows he is "the voice of amateur radio in the loudspeakers

of the world." He has no silly phonetic identification such as, "Double-you One

Little Vicious QRMer," for he knows the boys will laugh at him, not with him. He

does not believe in the false modesty of an editorial "we" if his is a one-operator

station. Neither does he use the trite, "The handle here is Joe"; if his name is

Joe, he says so. He does not chide his wife for listening to the morning radio serials

or "soap operas" and then give the same sort of performance during his ham contacts.

Yes, we previously said, "Be an individual." There's a difference between being

an individual and being a screwball. The point is in how we conduct our contacts.

The thoughtful amateur must today give particular consideration to the beginner.

There are thousands of LSPH-newcomers, the accumulation from four years of amateur

shutdown; and there are thousands more to come, many from the ranks of returning

veterans. Today's beginners are tomorrow's regulars, and if we want capable operators

for our future brothers we must get them started right by lending a helping hand

on the air. Keep an ear open for signals with unsteady sending, particularly if

they sign calls well down the alphabet. A poor operator you hear may be only a beginner

who needs guidance; a poor operator is a lid only when he refuses to try to improve

his habits.

The smart amateur is interested in improving his operating ability, because he

knows it will add to his operating fun and accomplishments. When he is scored on

a bad habit he does not whine, "Heck, it's only ham radio," and then, ostrich-like,

stick his head in the sand. Sure, it's only ham radio. Whistling at a sweet young

thing is only wolfing, too - but there are good and bad methods, and the good ones

payoff!

Bibliography

"How to Operate Well," QST, Nov., 1939.

"Personality Over the Air," QST, Jan., 1940.

"Say It With Words," QST, June, 1940.

"Self-Training Hints for Voice Operators," QST, Feb., 1941.

"This Business of Code," QST, Feb., 1941.

"The Secrets of Good Sending," QST, Sept.-Oct., 1941.

"We're Off" (Editorial), QST, Dec., 1945.

Operating an Amateur Radio Station, free on request to ARRL members.

See also "Operating Practices" tabulation in pre-war yearly QST index (December

issue).

*Assistant Secretary, ARRL.

Posted October 11, 2022

(updated from original post

on 2/28/2016)

|