October 1966 QST

Table

of Contents Table

of Contents

Wax nostalgic about and learn from the history of early electronics. See articles

from

QST, published December 1915 - present (visit ARRL

for info). All copyrights hereby acknowledged.

|

The concept of a field effect transistor

(FET) has been around in theory for a long time*, but manufacturable devices arrived

in designers' labs not until the early 1960s. This article from the October 1966

edition of QST magazine gives a good introduction to the physics of a basic

FET as well as the junction FET (JFET) and the insulated gate FET (IGFET), all of

which are still in widespread use today. What you learn about them here is applicable

today. In fact, I swear some of the drawings are the same ones that appeared in

my college semiconductor physics text books (admittedly from the late 1980s, so

not too much of a surprise).

* Per Wikipedia,

"The field-effect transistor was first patented by Julius Edgar Lilienfeld in 1926

and by Oskar Heil in 1934, but practical semi-conducting devices (the JFET) were

only developed much later after the transistor effect was observed and explained

by the team of William Shockley at Bell Labs in 1947. The MOSFET, which largely

superseded the JFET and had a more profound effect on electronic development, was

first proposed by Dawon Kahng in 1960."

Field-Effect Transistors

What They Are-How They Work

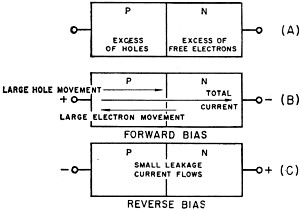

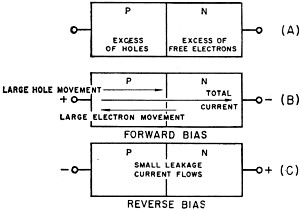

Fig. 1 - Action of p-n junction when bias is applied.

By Jim George, W7AWH

A recently introduced semiconductor device called the field-effect transistor,

or FET for short, combines some of the best features of both the vacuum tube and

the transistor. The FET is appearing in new electronic circuits of all types and

will soon be used in amateur radio equipment. A great deal of excitement centers

about this solid-state device which acts much like a vacuum tube, and it is the

purpose of this article to describe its construction and operation.

Before getting into device characteristics, let us quickly review some basic

concepts in semiconductors. Useful semiconductor material is either p-type, where

holes (a hole is actually a place where there is no electron) are concentrated relatively

heavily, or n-type which features an excess of free electrons. Both the holes and

free electrons are the current carriers in a piece of semiconductor, just as free

electrons only are the current carriers in a piece of copper. As a memory aid, remember

that the "p" in p-type material stands for the positive charge of the current carriers

(holes) and the "n" stands for the negative charge of the current carriers (free

electrons) in n-type semiconductor material. When p-type material and n-type material

are brought together, a p-n junction is formed as shown in Fig. 1A.

The field-effect transistor, for the last few years a tantalizing promise of better

things in semiconductor devices, is now rapidly coming into the market at prices

attractive to amateurs. We've already shown you one application in Walt Lange's

audio oscillator (July QST). Here's the background story of the FET - how it's made

and how it functions, and why it will be superior to older transistor types in many

applications.

The Junction Diode

The resulting action of a p-n junction is well known. When a forward bias is

applied as shown in Fig. 1B, a large current will flow. The total current is

made up of the electron current plus the hole current. When reverse bias (Fig. 1C)

i applied, only a small reverse current flows - the p-n junction acts as a diode.

It is important to note the reverse-bias case. We know that when a voltage is applied

to a resistive network, this voltage is dissipated by IR drops until the applied

voltage is "used up" by the sum total of all the voltage drops. The same principle

applies to the case of the reverse-biased p-n junction diode. We have applied V

volts of reverse bias and this voltage must be used up somehow in our circuit, the

p-n junction. The resulting action is shown in Fig. 2, where charges are separated

in a region close to the junction. Enough charges are moved until the electric field

across the junction produces a voltage drop which is approximately equal to our

applied voltage. The important point here is that the region around the p-n junction

is now depleted of all its holes and free electrons, thus there are no current carriers

available. This region is commonly called the "depletion region" and it sounds reasonable

that its thickness depends on the magnitude of reverse voltage which is applied.

It will be an important point in the operation of field-effect transistors that

no current can flow in the depletion region since there are no current carriers

in that region.

Fig. 2 - Reverse bias causes electrons and holes to move

away from the p-n junction, leaving a depletion region (shaded area) and no current

flows.

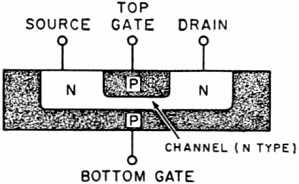

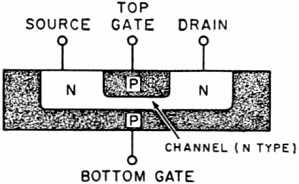

Fig. 3 - The junction field-effect transistor (JFET).

Fig. 4 - Operation of the JFET under applied bias. A depletion

region (light shading) is formed, compressing the channel and increasing its resistance

to current flow.

Fig. 5 - The insulated-gate field-effect transistor (IGFET).

The Junction FET (JFET)

Field-effect transistors are divided into two main groups: junction FETs, and

insulated-gate FETs. We will discuss the Junction FET, or JFET, first. The basic

JFET device is shown in Fig. 3.

First of all, note the location of the terminals where voltages can be applied.

The reason for the terminal names will become clear later. A d.c. operating condition

is set up by starting a current flow between source and drain. This current flow

is made up of free electrons since the semiconductor is n-type in the channel, so

a positive voltage is applied at the drain. This positive voltage attracts the negatively-charged

free electrons and the current flows (Fig. 4A). The next step is to apply

a gate voltage of the polarity shown in Fig. 4B. Note that this reverse-biases

the gates with respect to the source, channel, and drain. This reverse-bias gate

voltage causes a depletion layer to be formed which takes up part of the channel,

and since the electrons now have less volume in which to move the resistance is

greater and the current between source and drain is reduced. If we apply a large

gate voltage, we cause the depletion regions to meet, and in this case the source-drain

current is reduced nearly to zero. Since we changed the large source-drain current

with a relatively small gate-voltage, we have a device which acts as an amplifier.

Further, note that in the operation of the JFET, the gate terminal is never forward

biased, because if it were the source-drain current would all be diverted through

the forward-biased gate junction diode.

The resistance between the gate terminal and the rest of the device is very high,

since the gate terminal is always reverse biased, so the JFET has a very high input

resistance. The source terminal is the source of current carriers, and they are

drained out of the circuit at the drain. The gate opens and closes the amount of

channel current which flows. It is seen how the operation of a FET closely resembles

the operation of the vacuum tube with its high grid input impedance. Comparing the

JFET to a vacuum tube, the source corresponds to the cathode, the gate to the grid,

and the drain to the plate.

Insulated-Gate FET (IGFET)

The other large family which makes up field-effect transistors is the insulated-gate

field-effect transistor, or IGFET, which is pictured schematically in Fig. 5.

In order to set up a d.c. operating condition, a positive polarity is applied to

the drain terminal. The substrate is connected to the source, and both are at ground

potential, so the channel electrons are attracted to the positive drain and we now

have a d.c. source-drain current. In order to regulate this current, we apply voltage

to the gate contact. Note that the gate is insulated from the rest of the device

by a piece of insulating glass so this is not a p-n junction between the gate and

the device - thus the name insulated gate. When a negative gate polarity is applied,

positively-charged holes from the p-type substrate are attracted towards the gate

and the conducting channel is made more narrow; thus the source-drain current is

reduced. When we connect a positive gate voltage, the holes in the substrate are

repelled away, the conducting channel is made larger, and the source-drain current

is increased. As can be seen, the IGFET is more flexible since we can apply either

a positive or negative voltage to the gate. The resistance between the gate and

the rest of the device is extremely high because they are separated by a layer of

glass - not as clear as your window glass, but it conducts just as poorly. Thus

the IGFET has an extremely high input impedance. In fact, since the leakage through

the insulating glass is generally much smaller than through the reverse-biased p-n

gate junction in the JFET, the IGFET has a much higher input impedance. Typical

values of Rin for the IGFET are over a million megohms, while Rin

for the JFET ranges from megohms to over a thousand megohms.

Fig. 6 - Typical JFET characteristic curves. | Fig. 7

- Typical IGFET characteristic curves. | Fig. 8 - Typical vacuum-tube characteristic

curves.

Fig. 9 - Symbols for most-commonly available field-effect

transistors.

Fig. 10 - Typical JFET crystal-oscillator circuit.

Characteristic Curves

The characteristic curves for the FETs described above are shown in Figs. 6 and

7, where drain-source current is plotted against drain-source voltage for given

values of the gate voltage. Note the similarity to the family of a vacuum-tube pentode

as shown in Fig. 8, where plate current is plotted against plate voltage for

varying amounts of grid voltage.

In discussing the JFET so far we have left both gates separate so the device

can be used as a tetrode in mixer applications. However, the gates can be internally

connected for triode applications. When using the IGFET the substrate is always

a.c.-shorted to the source, and only the insulated gate is used to control the current

flow. This is done so that both positive and negative polarities can be applied

to the device, as opposed to JFET operation where only one polarity can be used,

because if the gate itself becomes forward biased the unit is no longer useful.

Classifications

Field-effect transistors are classed in to two main grouping for application

in circuits, enhancement mode and depletion mode. The enhancement-mode devices are

those specifically constructed so that they have no channel. They become useful

only when we apply a gate voltage which causes a channel to be formed. IGFETs can

be used as enhancement-mode devices since both polarities can be applied to the

gate without the gate becoming forward biased and conducting current.

A depletion-mode unit corresponds to Figs. 3 and 5 shown earlier, where a channel

exists with no gate voltage applied. For the JFET we can apply a gate voltage and

deplete the channel, causing the current to decrease. With the IGFET we can apply

a gate voltage of either polarity so the device can be depleted (current decreased)

or enhanced (current increased).

To Slim up, a depletion-mode FET is one which has a channel constructed; thus

it has a current flow for zero gate voltage. Enhancement-mode FETs are those which

have no channel, so no current flows with zero gate voltage . The latter type devices

are especially useful in logic application.

Circuit symbols approved for FETs are shown in Fig. 9. Both depletion-mode

and enhancement-mode devices are illustrated.

Applications

Some applications for FETs are shown in Figs. 10 and 11. In Fig. 10 a JFET

oscillator is pictured, and a versatile FET d.c. voltmeter (FETVM) is shown in Fig. 11.

The voltmeter features two Motorola 2N4221 JFETs and offers the high input impedance

(22 megohms on all ranges in Fig. 11) of a v.t.v.m, but with more stability.

The circuit is essentially a differential amplifier which works on the principle

that the current through a resistance is directly proportional to the difference

between the voltages at its ends. When R1 and R2 are adjusted

so that the voltage at the emitter of Q2 is equal to the voltage at the

emitter of Q3, with no input signal, the voltage difference is zero and

no current will flow through the meter.

Fig. 11 - D.C. voltmeter circuit using field-effect transistor. Resistances

are in ohms (K = 1000); fixed resistors are 1/2 watt. The second position of S3

is used for checking battery voltage.

M1-0-100 microammeter.

S1-D.p.s.t. toggle.

S2-D.p.d.t. toggle.

S3-Rotary, 1 section, 1 pole,7 positions.

R1 R2 R3-Linear controls

(R2 and R3 are panel adjustments; R1 can be internal).

R4-R9 inc.-Trimming potentiometers,

for internal mounting (Mallory MTC or equivalent).

When the voltage at the gate, G, of Q1 is raised to 0.3 volt the voltage

across the meter circuit also is approximately 0.3 volt since the source followers

and emitter followers have a voltage gain of approximately one. R3 is

then adjusted to give full-scale meter deflection. The calibration resistors, R4-R9

inclusive, are individually adjusted for exactly full-scale deflection on each range

when the maximum voltage for that range is applied to the input terminals through

the range switch, S2.An accurate voltmeter should be used to check the

applied voltage when setting the calibration resistors.

These two circuits were furnished by Don Wollesen and Walter Birks of the Applications

Engineering Group at Motorola Semiconductor Products Division.

This article has provided a basic look into the FET and some of its applications.

In general, the FET offers much improved noise performance, stability, and cross-modulation

resistance over either vacuum tubes or standard transistors (p-n-p, n-p-n). Its

many features, such as high input impedance and desirable high-frequency performance,

insure its design into a vast number of electronic circuits in the near future.

It is probably the most recent radical improvement in device design, and should

prove most interesting to amateur radio operators everywhere, allowing them greatly

improved freedom in circuit design.

* c/o Motorola Semiconductor Products, Inc., 5005 East McDowell Road, Phoenix,

Ariz. 85008

Posted August 23, 2024

(updated from original

post on 2/13/2013)

|