|

July 1949 Popular Science

[Table of Contents] [Table of Contents]

Wax nostalgic about and learn from the history of early

electronics. See articles from

Popular

Science, published 1872-2021. All copyrights hereby acknowledged.

|

Back in my days of doing

electrical work, prior to entering the USAF, I seriously considered training as

a lineman. At some point I decided I rather pursue electronics rather than high

voltage electrical networks. This 1949 Popular Electronics magazine

article does a great job of presenting the kinds of skills and risks that go

along with being a lineman. Today's high-tension linemen benefit from advanced

equipment like two-way radios, mechanical augers, and specialized tools that

streamline repairs and improve safety. Rubber gloves, sleeves, and protective

gear are rigorously tested, while "line hoses" and insulator hoods shield

workers from live wires. Despite these advancements, the job remains perilous,

demanding unwavering adherence to safety protocols, especially during inclement

weather and emergency repair jobs. Training is now more structured - apprentices

spend years mastering skills under seasoned professionals before handling

high-voltage lines. Speed is no longer prized; meticulous caution is. Even

"dead" wires are treated as hazardous, and linemen must remain vigilant against

static electricity or accidental contact. Modern technology may make the work

faster and safer, but the core principle remains unchanged: a single lapse can

be fatal. Linemen must still combine mechanical skill, electrical expertise, and

unshakable discipline to keep the power flowing... safely.

How Linemen Handle Hot Wires and Stay Alive

Held only by his safety belt, a veteran lineman hangs far out

in space to repair a power line. But he had to go to school to learn how.

It takes years to train a high-tension man to work with death only an

elbow away - and keep it there.

By George H. Waltz, Jr.

PS photos by Hubert Luckett

The summer's first big electrical storm had hit. Lightning, wind, and falling

trees knocked out a power line. A third of the town was plunged into darkness -

including the hospital. When its superintendent frantically called the power company,

he was told:

"You'll have electricity within half an hour." Just 22 minutes late; the lights

flashed on.

Emergencies like this break suddenly upon thousands of communities every year.

But in spite of hurricanes, ice storms, blizzards, floods, and direct hits by thunderbolts,

vital electricity is kept flowing across the country with a minimum of interruption.

How do our power companies perform these high-speed repair miracles?

Part of the answer is two-way radio, special equipment, and trucks that are complete

mobile workshops for the line crews. But a bigger part is the skill and versatility

of the pole-climbing linemen themselves.

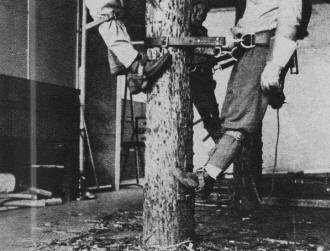

What well-dressed lineman wears is shown above and below. Hands

and arms are completely covered by heavy rubber gloves and sleeves.

Rest of outfit includes climbing irons, goggles, and body belt

that holds tools and safety belt. Peaked cap shield head, shades eyes against sun

glare.

Linemen test rubber gloves before each climb by filling them

with air, closing the wrists, and squeezing. Any air leaks then show up tiny, pin-point

holes that would be extremely dangerous.

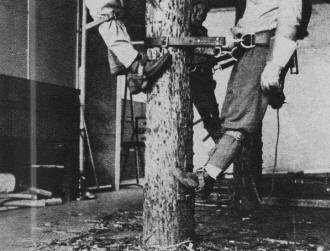

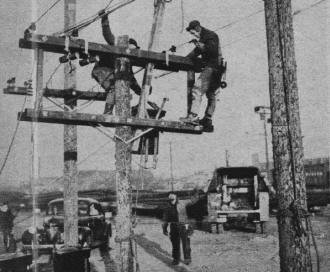

As lineman climbs up pole, he covers all wires he must pass with

long, tubular, slip-on insulators called "line hoses." Where voltage is high, all

wires are covered with rubber protectors.

Two-way radios in line trucks speed emergency repairs by keeping

field crews constantly in touch with central dispatcher who directs trucks, issues

orders, and co-ordinates activities of crews.

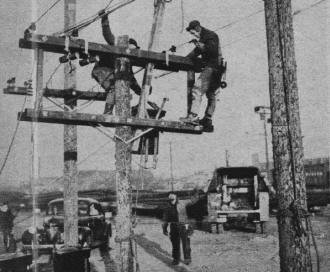

New pole holes are quickly dug to right depth by a mechanical

auger mounted on the rear of a special truck. A derrick, also mounted on the truck,

then lifts the pole and lowers it in place.

Picking up small nails would be difficult trick for lineman wearing

heavy gloves, so nails are hoisted up to him stuck through rope. When he needs one,

he simply pulls it out of the rope.

To cut high-tension wires, linemen use special wood-handled hack

saw, never ordinary wire cutters. Note how surrounding lines and insulators have

been covered with "hoses" and "hoods."

Linemen must learn to be fire fighters, too. Here one battles

a hard-to-reach, pole-top fire with an extinguisher containing a special mixture

of carbon dioxide and carbon tetrachloride.

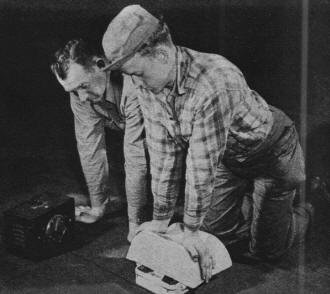

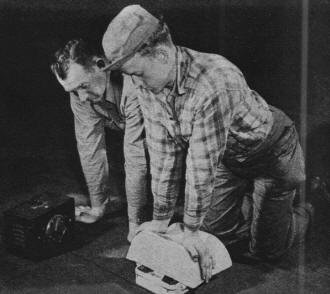

In case of accidents, linemen must be able to apply artificial

respiration - even at pole top. Mastery of prone method is aided by scales and timer

to show the proper pressure and timing.

Each lineman who has won his climbing spurs is a mechanic, electrician, woodsman,

aerialist, carpenter, gadgeteer, and first-aider all in one. I saw all these skills

in action when I recently spent a week with an emergency crew of the Public Service

Electric and Gas Company of New Jersey.

There was a time years ago when linemen were rugged rovers who went wherever

there was work. They prided themselves on how fast they could climb a pole and come

down in two or three jumps. They learned to be linemen by experience-and often suffered,

sometimes fatally, from lack of experience.

Not so today. In most cases it now takes a lineman longer to win his Grade I

spurs than it does a college student to get his degree. After spending three years

as a line helper, or "groundhog," he then divides his time for the next two years

between the linemen's school and actual work in the field under old-timers. Speed

in getting up and down a pole no longer is the lineman's goal. One of the first

lessons he learns is that haste not only makes waste but also danger.

Let's follow the typical career of a young man we'll call John Clure. When John

graduated from his New Jersey high school, he heard that Public Service was looking

for line-men trainees. John had always been handy with tools; but, being an athlete

and liking the outdoors, he couldn't quite reconcile himself to a stuffy bench job

indoors. Line work seemed like a good way of combining his abilities.

That summer John began as a helper on a line crew. For the next 36 months, he

toted, shoveled, wielded an axe, and learned to use a pike - the long, steel-pointed

poles used to maneuver a line pole into place. When it carne time for John to go

to line school, he had a good ground's-eye picture of the job he hoped to fill.

Broken power lines are reconnected by a mechanical splice

called a compression connector. Hand splices are seldom used, although all linemen

know how to make them. Heavy cable clipped on wire to right of lineman is mechanical

jumper that shunts current around break until it is repaired. This permits linemen

to work directly on live wires without shutting off power.

Lineman Stakes Life on "Gaffs"

At school, the first thing he learned was that his climbers were his most important

pieces of personal equipment. From then on his life would depend on them. He was

shown how the metal spurs or gaffs must be kept sharp by filing them to a special

three-sided point to match a gauge. His instructor showed him how a poorly sharpened

gaff can cut out of a pole and possibly cost him his life. For the first time, he

strapped on his "waistline workshop," the body belt that holds a lineman's pliers,

skinning knife, wrenches, parts bag, screw driver, folding rule, connectors, a bag

for his all-important rubber gloves, and safety belt. By the end of his first school

day, John had taken his first timid step up a practice pole in the school's pole

yard.

During this early stage, John was a "termite," the name often jokingly given

new linemen because of the mounds of chips that pile up around the practice poles.

The tenth day in school found John perched at the top of a 40-foot pole for the

first time. He had worked himself there by easy stages, climbing a little higher

each day. John admits now that he felt a little scared that first time at pole top,

but he wasn't half as upset as one boy who two-thirds of the way up literally froze

to the pole with fright. He could move neither up nor down, and his instructor finally

had to climb up and bring him down.

An instructor likes to pick a slightly overcast day for this important pole-top

test, the kind of day when clouds are scudding across the sky. He then orders each

beginner to climb his pole with his back to the oncoming clouds. If a student has

the slightest tendency toward dizziness or height fright, one look at the sky will

make it blossom out like measles. The clouds, passing over him from back to front,

make him feel that he is falling backwards. If he can't shake off the illusion,

he is likely to freeze, grabbing the pole with both hands and hanging on. This is

the student lineman's first big hurdle.

John Learns on a "Stub" Pole

For six weeks, John learned his pole work literally from the ground up. Each

new problem of construction and wire work he first solved at the top of a "stub"

pole just a few feet off the ground. As he became more confident, he proceeded higher

and higher to pole top. A lineman not only has to become apt in each of the many

jobs he has to perform, but he has to feel at home resting on his climbers and safety

belt.

As one veteran lineman put it: "You've got to be relaxed up there. Handling hot

wires, you've got to concentrate on the job -not on your legs and spurs. The first

couple of months are tough. You're dog-tired before the day is half over. Going

up, you dig your spurs in too deep and then have to use extra effort to pull them

out. Topside, you stiffen up. You haven't learned yet to relax and lean back on

your belt. But you'll get it, and then it'll be easy."

At the end of seven weeks of basic training, John left the line school as a Grade

II lineman and reported to a line crew for his first real field work. But here again

he progressed by easy stages. His pole work was limited either to working alone

on low-voltage lines that were dead, or working with another qualified Grade II

lineman on low-voltage lines that were alive.

For the next year and a half, John shuttled back and forth between the school

and the field, learning more at each stage. At the end, handling high-tension wires

was relatively safe and easy at just about any height. He was a Grade I lineman.

Safety becomes second nature to a well-trained lineman. From the time he was

a groundman he has worked with a hat on and his shirt sleeves rolled down even in

the hottest weather. Rolled-up sleeves may be more comfortable on a sizzling summer

day, but unabsorbed perspiration on bare arms can cause deadly current leakages

around a lineman's gloves and rubber sleeves.

Linemen steady new pole with long, steel-pointed "pikes" while

hole is filled in. Wires from old pole, removed but still standing, will be transferred

to new one when it is firmly in place.

No termite could do a more thorough job of chewing up this practice

pole than spurs of student linemen. The pile of chips at base of pole shows why

trainees are aptly dubbed "termites." Learning from the ground up - literally.

Students practice on stub poles that are exactly like real ones

- except closer to terra firma. Here they perfect their skills and gain confidence.

Lineman's life depends on his climbing irons. To prevent them

from cutting out, they must be kept filed to special three-sided point. Here metal

gauge is used to check accuracy of shape.

He knows the danger of finger rings, watches, fasteners, and key rings. Any piece

of metal, even a metal button on his cap, can help to form an accidental spot contact

for high-voltage current. Before he climbs a pole, he tests his rubber gloves for

dangerous leaks. He fills them with air and holds them closed by folding and rolling

down the wrists to make sure they hold the air and have no pin-point holes. Then

he pulls leather protecting gloves over the rubber gloves. If he is going to work

around high-voltage wires, he puts on his rubber sleeves.

As he climbs toward pole top, he covers all nearby wires with rubber blankets

and slip-on insulators called "line hoses" and "insulator hoods." "Covering up,"

as the linemen call it, is the first step on every job. Often a lineman will spend

half an hour "covering up" to make a repair that takes less than five minutes!

Even "Dead" Wires Can Kill

He has learned to regard any wire, "dead" or "alive," with the utmost respect.

He knows that under certain conditions even a "dead" wire can give him a fatal jolt.

A long, unconnected wire stretching for many miles, particularly at the high altitudes

encountered when stringing power lines over mountains, can develop a charge of static

electricity heavy enough to kill a man.

Ask the average lineman what he does with his spare time and you'll probably

find that his yen for using his hands and building things doesn't stop when he puts

away his climbers at the end of a day. The chances are he'll tell you he spends

a good many of his evenings either in his home workshop or doing odd jobs around

the house - something different like rewiring a living-room lamp or fixing the vacuum

cleaner. He'll tell you, too, that he handles no volts with as much respect as any

high-tension line.

|