|

June 1957 Popular Electronics

Table of Contents Table of Contents

Wax nostalgic about and learn from the history of early electronics. See articles

from

Popular Electronics,

published October 1954 - April 1985. All copyrights are hereby acknowledged.

|

Here is a great primer on

the operation of traveling wave tubes (TWT). A controversy exists over who first

invented the TWT -

Bell Telephone Labs' Dr. Rudolf Kompfner, or Andrei Haeff while at the Kellogg

Radiation Laboratory at Caltech. Regardless of its provenance, the device was a

major advancement in the development of high power microwaves. A TWT amplifies broadband

microwaves continuously: an electron gun emits a high-speed beam through a vacuum

tube, interacting with the weak input signal propagating along a helical slow-wave

structure. The helix slows the signal's phase velocity to sync with the electrons,

whose velocity is modulated by the signal's electric field, bunching them into dense

clouds that transfer kinetic energy back to the wave for substantial gain before

collector absorption. In contrast, the narrowband klystron velocity-modulates the

beam discretely in an input cavity, allows drift bunching, then extracts power in

an output cavity for high gain/efficiency. The magnetron oscillates without input:

a rotating electron cloud in crossed E/B fields couples to resonant cavities, yielding

high power/tunability.

After Class: The Traveling-Wave Tube

Special Information on Radio, TV Radar and Nucleonics Special Information on Radio, TV Radar and Nucleonics

Ethylene glycol, a chemical obtained as a byproduct in the manufacture of certain

synthetics, was once unceremoniously dumped into the waters of the Delaware River.

Then someone discovered that it possessed unique anti-freeze properties. The waste

disposal chute was promptly diverted from the river into gallon cans which today,

under the name of "Prestone," sell for $3.75 each!

The same kind of thing has happened in the development of microwave electron

tubes. Ordinary triodes and pentodes are very satisfactory amplifiers at medium

frequencies, but they begin to misbehave at the ultra-high frequency end of the

spectrum. Among the more important causes of this misbehavior is the effect called

electron transit time, an effect in which the time required for an electron to travel

from the cathode to the plate of a tube is almost as great as the time needed for

the r.f. signal to complete one full cycle. This effect renders the tube incapable

of "following" the signal frequency, so that it fails completely as an amplifier

or oscillator.

What it looks like. Here, low-level, low-noise traveling-wave

tubes are shown undergoing a final check at RCA Tube Division, Harrison, N. J.

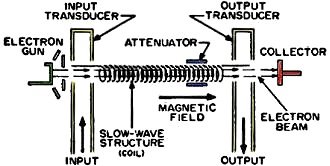

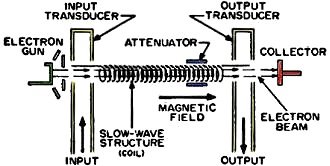

Fig. 1 - Functional diagram showing bask components of a traveling-wave

tube amplifier.

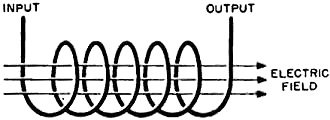

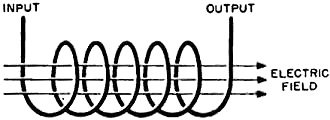

Fig. 2 - To understand how the traveling-wave tube operates,

keep in mind that a u.h.f. wave on the coil produces an electric field.

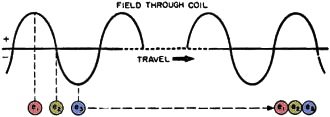

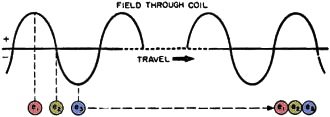

Fig. 3 - Electrons travel from left to right, but they are bunched

together due to the field in the coil. See text.

Like the man with the anti-freeze inspiration, ingenious electronic engineers

have designed microwave tubes which actually make use of the transit time effect

in generating and amplifying frequencies so high in the spectrum that they approach

the wavelengths of light. Now, instead of preventing microwave operation, electron

transit time phenomena enable us to work with frequencies higher than 50,000 megacycles!

The traveling-wave tube is an example of such an application. One can hardly scratch

the surface of microwave techniques without coming upon this tube or others like

the klystron and magnetron.

Basic Parts

All traveling-wave tube amplifiers incorporate the basic parts shown in Fig.

1. These include an electron gun - such as one finds in the picture tube of a TV

set, a "slow-wave" structure - generally in the form of a loosely wound coil, a

collector which receives the electron beam at What it looks like. Here, low-level,

low-noise traveling-wave tubes are shown undergoing a final check at RCA Tube Division,

Harrison, N. J. the other end of the tube, and an attenuator for preventing unwanted

oscillations.

The electron gun produces a beam of electrons which moves through the hollow

center of the coil. It is restricted to a tight beam by a strong magnetic field

around the body of the tube (not shown in the diagram). Its velocity is controlled

by varying the d.c. voltage between the coil and the cathode of the gun. If nothing

more were done, the beam would simply move through the length of the coil in a uniform

stream as in Fig. 2 and be returned to the circuit via the collector electrode.

But something else must happen if amplification is to be realized.

How Wave Travels

Imagine that a radio signal of ultra-high frequency - say 20,000 mc. - is applied

to the coil. Such a wave travels at a speed approaching the velocity of light -

186,000 miles per second - around the turns of the coil. It does not advance from

one end of the tube to the other end of the tube at this rate, however.

The actual velocity of propagation of the wave along the axis of the coil is

found by multiplying the speed of light by the distance between turns of the coil

and dividing the product by the circumference of the individual turns:

rate of advance = (velocity of light) x (turn spacing)

/ (turn circumference)

Since the ratio of turn spacing to turn circumference is always a small fraction,

the total product is considerably less than the speed of light.

While the wave moves around the turns of the coil, it thus produces an electric

field through the axis of the coil which moves with this velocity, as shown in Fig.

2. The electric field advances from one end of the tube to the other and, as it

does so, an interaction takes place between the moving field and the electron beam

from the cathode gun. This interaction results in delivery of energy from the electron

beam to the wave from the coil, causing the signal to become larger as the coil's

output end is approached.

Energy Transfer

The electric field moving axially through the coil consists of ultra-high frequency

pulsations which alternate into the positive and negative regions. This is illustrated

as a wave on the horizontal axis in Fig. 3. Let us consider three electrons, e1,

e2, and e3, which belong to the beam passing through the coil,

and observe them at the time shown in Fig. 3. At this instant, e1 is

in the presence of a positive portion of the field and is therefore accelerated

in its motion through the coil. The velocity of electron e2 remains unaffected,

however, because it is in a position of zero field strength while e, is decelerated,

being enmeshed in a field of negative polarity. This starts a bunching process in

which all the electrons in the immediate vicinity of e2 begin to concentrate

around this particle, some decelerating while e, catches up with them while others

speed up to overtake e3.

As the wave continues through the axis of the tube, the bunching action intensifies.

This strong concentration of moving electrons induces a second wave in the coil

which lags behind the original signal wave. The effect of this lag is to produce

a new decelerating action on the electron beam.

Amplification

At this point we have to draw upon the Law of Conservation of Energy to understand

how amplification is produced. Energy can neither be created nor destroyed but only

changed in form. Before being decelerated; the electrons in the beam possess a given

amount of kinetic energy. Conservation tells us that when they are decelerated the

energy these electrons lose must be transferred to the agent which has caused the

slow-down. Thus, the electron beam adds some of its energy to the content of the

signal, causing the latter to emerge from the output end of the coil larger than

it was when it first entered. Hence, amplification has been realized.

Our troubles are not yet over, however. Whenever a wave travels through a guiding

medium, there are likely to be reflections from the remote end. In the traveling-wave

tube, such reflections are prone to start oscillations which, of course, are highly

undesirable in an amplifier. This tendency is controlled by introducing an attenuator

near the output end of the tube, usually in the form of a coating of graphite inside

the glass. This conductive area absorbs energy from the reflections, preventing

them from reaching the input end of the tube in sufficient strength to maintain

oscillatory feedback.

One of the most appealing features of traveling-wave tubes is their ability to

amplify all signals over a very wide band of frequencies. Familiar amplifier circuits

for radio frequencies usually involve resonant circuits which tend to limit the

passband by the very nature of their resonance curves. The traveling-wave tube,

being an essentially non-resonant device, is not limited in this manner. A well-

designed traveling-wave tube can provide approximately equal amplification over

the unbelievably wide band of 2000 mc!

|

Special Information on Radio, TV Radar and Nucleonics

Special Information on Radio, TV Radar and Nucleonics