|

November 1962 Popular Electronics

Table of Contents Table of Contents

Wax nostalgic about and learn from the history of early electronics. See articles

from

Popular Electronics,

published October 1954 - April 1985. All copyrights are hereby acknowledged.

|

Louis Garner was the

semiconductor guru for Popular Electronics magazine in the 1960s when

he wrote this article attempting to demystify the proliferation of over 2,000

transistor types. He devised a "transistor tree," tracing evolution from the

obsolete point-contact transistor - unstable with high gain but noisy - to

advanced designs balancing cost, frequency, power, and reliability. It covers

pnp and npn basics, then details processes: grown-junction (inexpensive, good

high-frequency); meltback diffused (similar, better response); alloyed-junction

(popular for power); surface-barrier family (SB, SBDT, MA, MADT; excellent

high-frequency, low voltage); post-alloy-diffused (PADT; thin base for speed);

mesa (etched table-like structure, high-frequency power); epitaxial mesa/planar

(optimized layers for voltage/frequency); and planar/epitaxial planar (diffused

silicon, stable, passivated). Emerging field-effect transistors offer high

impedance like vacuum tubes.

Transistors: Types & Techniques

The transistor tree groups together similar types in branches.

Field-effect transistors are the beginning of a new semiconductor tree.

Do epitaxial, alloyed junction, MADT, and mesa transistor types confuse you?

Discover the transistor tree and you'll know the "how" and "why" for each

By Louis E. Garner, Jr.

Semiconductor Editor

Since the invention of the transistor over a decade ago, manufacturers have been

constantly seeking new methods to produce better and more reliable units - transistors

that would not only have a broader range of operating capabilities, but also be

lower priced. Often, a process has been developed which is capable of producing

low-cost units. But, by its very nature, such a technique has resulted only in low-frequency

(audio) types. Another process may deliver extremely high frequency units, or transistors

with closely controlled characteristics, but be rather expensive.

The net result has been a great variety of transistor types-over 2000 at last

count-made by a dozen or more processes. Today, transistors are available with betas

(gains) from 5 to over 50,000, power-handling capacities from milliwatts to hundreds

of watts, and frequency capabilities from d.c. to thousands of megacycles. Prices,

too, vary just as widely-from less than 50 cents to over $100 each, even in production

quantities.

PNP and NPN

Except for specific electrical characteristics and maximum ratings, there are

only two general types of triode transistors: pnp and npn units. These two classifications

refer to the arrangement of the alternate layers of "p-type" and "n-type" semiconductor

material making up the device.

Whether the semiconductor material itself is basically germanium or silicon,

the "p -type" material conducts by means of the migration of positive charges (called

"holes"). Similarly, the "n-type" material conducts by means of the movement of

negatively charged free electrons through the crystalline structure.

The fact that many transistor manufacturers refer to their products primarily

in terms of their internal construction has led to a good deal of confusion for

newcomers to the electronics field (and, often, for "old-timers" as well). One firm

will refer to its line of surface-barrier transistors. Another will sing praises

about its high-quality mesa types. Still another will point out the advantages of

its planar units. Sometimes, even minor refinements in production techniques will

lead to new designations and such jawbreakers as VHF npn silicon epitaxial planar

transistor.

Such confusion, however, is really unnecessary - if you have some idea of what

each basic type is all about. Let's look over the transistor tree and see if we

can bring some order out of what may-for you-be chaos.

Point-Contact Transistor

Grown-Junction Transistor

Meltback Diffused Transistor

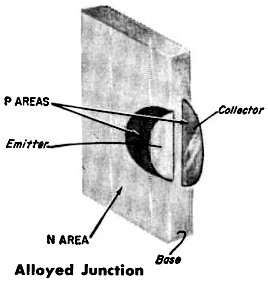

Alloyed-Junction Transistor

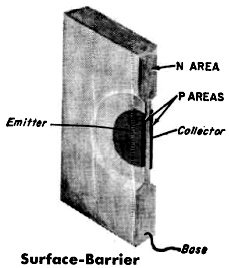

Surface-Barrier Transistor

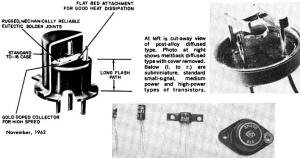

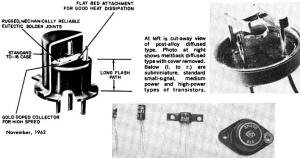

At left is cut-away view of post-alloy diffused type. Photo at

right shows meltback diffused type with cover removed. Below (l to r) are subminiature,

standard small-signal, medium power and high-power types of transistors.

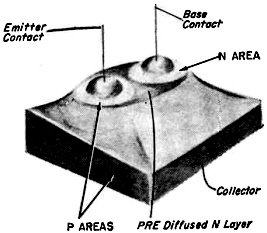

Post-Alloy-Diffused Transistor

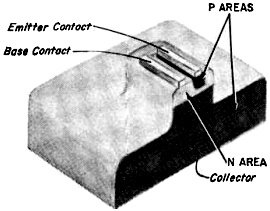

Mesa Transistor

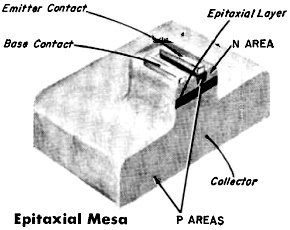

Epitaxial Mesa Transistor

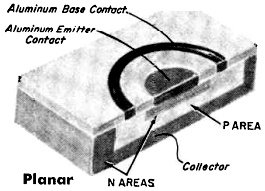

Planar Transistor

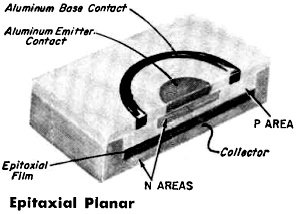

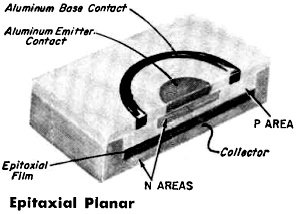

Epitaxial Planar Transistor

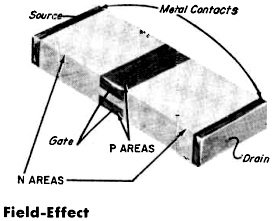

Field-Effect Transistor

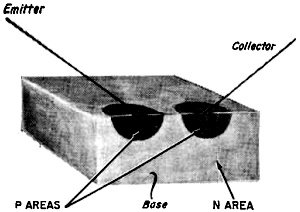

Point-Contact

Although now considered obsolete, the point-contact type was the original transistor...

the first, and for a while - the only, type produced. In its basic form, this type

of transistor is made up of a small cube of n-type semiconductor material to which

are attached two closely spaced fine metal wires or "cat's whiskers." The unit is

treated during the manufacturing process so that atoms from the contact wires migrate

into the semiconductor cube to form small p-type regions at their tips. One of the

wires serves as the emitter electrode, the other as the collector, and the semiconductor

cube is the transistor's base (hence the original name).

Point-contact transistors have extremely high gain and good high-frequency characteristics,

but they are also unstable, noisy, and difficult to manufacture. In addition, it

is difficult to produce this type of transistor to close production tolerances,

making the units quite expensive.

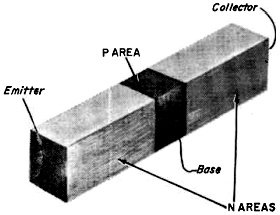

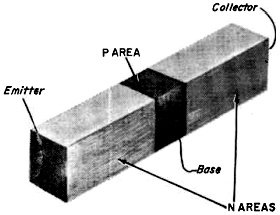

Grown-Junction

As the name implies, this type of transistor is made by "growing" the pn junctions

during the original crystal-forming process. Two basic types have been produced.

In one, the semiconductor material (germanium, for example) is "doped" with chemical

impurity elements to give it both n- and p-type properties with, say, the n-type

predominating.

During the crystal-forming process, the growing rate is altered, changing the

concentration of impurities so that alternate layers of p-type and n-type material

are formed. A transistor cut from a crystal formed by this process is identified

as a rate-grown type. (In a related manufacturing process, the concentration of

impurity elements is changed by the addition of extra chemicals as the crystal is

formed).

Physically, grown-junction transistors are all quite similar in appearance and

are essentially small rectangular bars of semiconductor material with alternating

layers of n- and p-type material. Grown-junction transistors are relatively easy

to manufacture and can be produced in large quantities inexpensively. In addition,

they offer good high-frequency characteristics, low noise figures, and reasonably

close tolerances.

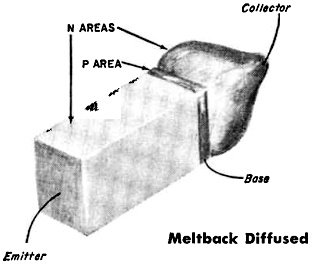

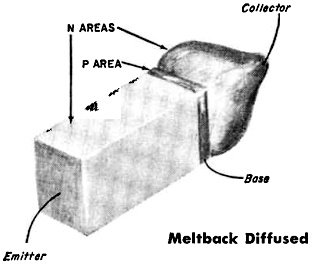

Meltback Diffused

This type of transistor is manufactured from a small rectangular bar of semiconductor

material similar in appearance to a rate-grown transistor. However, it is cut from

a crystal containing both n- and p-type impurity elements, with the n-type predominating.

One tip of the bar is melted into a drop and allowed to recrystallize. During the

"refreezing" process, the p-type element concentrates at the junction between the

melted and unmelted parts of the bar, forming a thin p-type base layer. The meltback

transistor has general characteristics very similar to those of grown-junction units,

but often with somewhat better high-frequency response.

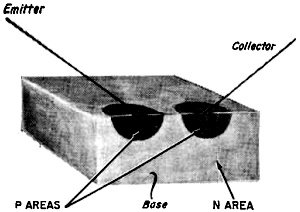

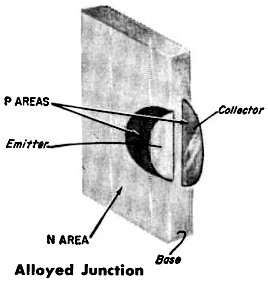

Alloyed Junction

As this is written, the alloyed junction transistor is perhaps the most popular

type. It is manufactured in both pnp and npn units and has a wide range of electrical

characteristics. The majority of high-power (multi-watt) transistors are alloyed

junction types. Again, the name gives a clue as to the manufacturing process, since

the transistor is produced by alloying small pellets of metallic impurity elements

to each side of a thin wafer of semiconductor material. If an n-type semiconductor

is used, for example, the metallic pellets might be of indium. During the alloying

process, the metal diffuses into the wafer, forming regions of the opposite type

of semiconductor on either side. The wafer itself becomes the base, while the opposite

regions become the emitter and collector electrodes. As a general rule, the collector

is made larger than the emitter.

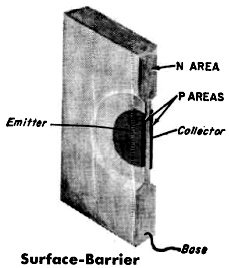

Surface-Barrier

Sometimes known as an SB type, the surface-barrier transistor is produced by

an electrochemical process which permits the formation of a very thin base region.

Typically, a wafer of n-type semiconductor material is placed between two very fine

streams of a metallic electrolytic solution. A d.c. potential is applied, causing

the solution to etch away the semiconductor material.

When the desired thickness is obtained, the d.c. polarity is reversed, permitting

the metallic solution to plate small metal dots on opposite sides of the etched-out

region. These metal dots become the emitter and collector electrodes, while the

etched-out wafer becomes the transistor's base. In some cases, the completed transistor

is heated in an oven, permitting atoms from the plated-on metal dots to diffuse

into the base wafer and forming a surface-barrier diffused type, or SBDT transistor.

A modified, but related, etching technique is used to produce microalloy (MA) and

microalloy diffused type (MADT) transistors. All transistors of the "surface-barrier"

family, including SBDT, SB, MA, and MADT types, are characterized by their excellent

high-frequency response, but limited voltage-handling capability.

Post-Alloy Diffused

This transistor, popularly known as a PADT type, is built up on a wafer of p-type

semiconductor (typically, germanium). A pre-diffusion process gives a controlled

depth of n-type material on the surface of the wafer. Later, two metallic pellets

are placed near each other on the n-side of the wafer. One pellet, which eventually

becomes the base electrode, contains only n-type impurity elements. The other contains

both n- and p-type impurities and eventually becomes the emitter. The wafer itself

becomes the collector.

The assembly is heated under controlled conditions and the impurities in the

base and emitter pellets diffuse into the semi-molten germanium. The n-type impurities

are chosen to have a high rate of diffusion and penetrate deeply into the wafer

to form an n-type layer. The p-type impurity in the emitter pellet diffuses slowly

and to a limited depth.

Upon cooling and recrystallization, the emitter pellet region is predominantly

p-type material and is separated from the p-type collector by a diffused n-type

layer which acts as the base. The resulting assembly is then etched and leads are

attached.

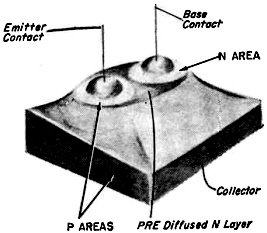

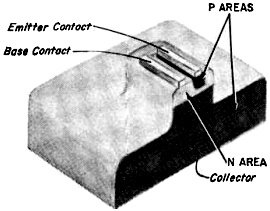

Mesa

This type of transistor derives its name from its physical appearance rather

than from the manufacturing process used. Under a powerful microscope, the mesa

transistor looks something like the flat-topped hills or mesas which characterize

the Southwest. The name, of course, is derived from the Spanish word for "table."

The manufacturing process is a relatively simple one. A layer of, say, p-type

semiconductor material serves as the collector. A thin film of n-type impurity is

vapor-diffused on top of the p-type material to form the base region. Finally, the

p-type emitter region is formed either by an alloying process or by vacuum evaporation

techniques. An etching process is then used to produce the table-like structure

which characterizes the mesa transistor.

Mesa transistors are theoretically inexpensive to produce, and they have excellent

high-frequency characteristics coupled with good power-handling capability.

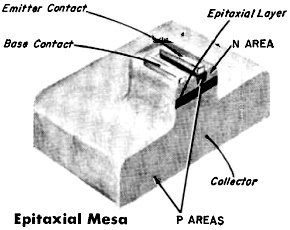

Epitaxial Mesa

Physically, the epitaxial mesa transistor looks just like its "first cousin,"

the conventional mesa type. The difference between the two lies in the formation

of a thin film between the diffused base region and the large p-type wafer which

normally serves as the collector electrode.

This film, known as an epitaxial layer because its crystalline structure is homogeneous

with that of the main body collector, serves as an intermediate collector electrode.

Even though it is the same basic p-type material, this film has electrical (resistivity)

characteristics which are different from that of the main body collector, permitting

the manufacturer to achieve an optimum compromise between breakdown voltage and

high-frequency characteristics.

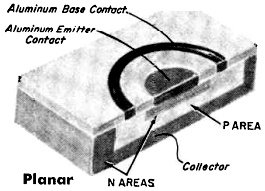

Planar

As might be suspected from its name, the planar transistor is formed on a relatively

flat surface or "plane," made by diffusing the emitter as well as the base regions.

In practice, a layer of, say, n-type semiconductor material (generally silicon)

serves as the collector. An oxide film is formed on the top surface to act as a

mask to prevent the diffusion of impurities into the material. Base and emitter

regions are then formed by removing portions of the oxide film and diffusing suitable

p- and n-type impurities into the collector.

The base and emitter regions are formed in sequential steps, with oxidation and

selective removal of oxide taking place prior to each diffusion step. Aluminum is

deposited on both the base and emitter regions to provide low -resistance contacts.

The final oxide film covers both junctions, preventing contamination and resulting

in a passivated device with good electrical stability.

Epitaxial Planar

This type of transistor is virtually identical to the planar type, except for

the addition of an epitaxial film, as discussed earlier. The manufacturing technique

is similar to that used for conventional planars. Both conventional and epitaxial

planar transistors couple superb high-frequency response with excellent electrical

stability. Their basic characteristics are similar to those of mesa types, except

for increased power handling capability and much lower leakage currents.

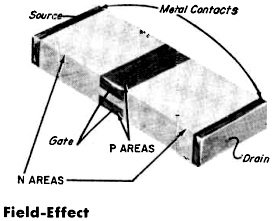

Field-Effect

A relatively new type, the field-effect device is a "transistor" only by definition,

since its construction and operating principles are different from those of more

familiar units. Even its electrodes have different names, being identified as source,

gate, and drain, rather than as emitter, base, and collector. It has an extremely

high input impedance (in the megohm range) and behaves somewhat like a low-voltage

vacuum tube.

A typical field-effect transistor consists of a bar of, say, n-type semiconductor

material (such as silicon) which has had p-type impurities introduced into opposite

sides, creating pn junctions and forming an n-type channel between the two p-type

regions. Metallic contacts are made at opposite ends of the bar to serve as the

source and drain electrodes, while the p-type regions become the control electrode

or gate.

In practice, the application of a reverse bias to the gate develops an internal

electrical field which limits the current flow between the source and drain electrodes.

Since the gate is reverse-biased, it presents a high input impedance to an external

signal source.

As this is written, the field-effect transistor is still considered a developmental

device. If it becomes popular, there is a good chance that a variety of construction

methods will be developed for it, just as they have for more familiar transistors.

|