July 1960 Popular Electronics

Table of Contents Table of Contents

Wax nostalgic about and learn from the history of early electronics. See articles

from

Popular Electronics,

published October 1954 - April 1985. All copyrights are hereby acknowledged.

|

How many of us have any idea

what a magnetic amplifier is or how they work? Very few, I would guess. This article

from a 1960 issue of Popular Electronics magazine is a good introduction.

Magnetic amplifier have been around since the beginning of the 20th century and

have been used extensively in heavy industrial and military equipment controls.

Their appearance is very similar to a typical electrical transformer, but the function

is completely different. Basically, the magnetic amplifier is a current-controlled

impedance changer. The current applied to the primary winding controls the degree

of saturation in the secondary, which in turn causes the impedance of the secondary

to vary. That action makes it functions like an electrically controlled rheostat.

Magnetic Amplifiers: How They Work, What They Do

By Ken Gilmore

The atomic submarine Triton glides swiftly and

silently through the deep. As its power plant purrs steadily, scores of electronic

watchdogs probe every part of the sub's powerful reactor. Suddenly the pressure

in a reaction chamber begins to rise over the allowable amount. One of the electronic

guardians instantly notes the rise and applies a corrective signal - before a human

operator could know that anything had begun to go wrong. The atomic submarine Triton glides swiftly and

silently through the deep. As its power plant purrs steadily, scores of electronic

watchdogs probe every part of the sub's powerful reactor. Suddenly the pressure

in a reaction chamber begins to rise over the allowable amount. One of the electronic

guardians instantly notes the rise and applies a corrective signal - before a human

operator could know that anything had begun to go wrong.

The electronic watchdogs that keep the Triton's

powerful nuclear plant operating without a hitch are magnetic amplifiers - almost

a hundred of them are used for this critical job. Yet these same magnetic amplifiers

- the heart of the control system of one of the world's most up-to-the-minute fighting

machines-are straight out of the horse-and-buggy era. The electronic watchdogs that keep the Triton's

powerful nuclear plant operating without a hitch are magnetic amplifiers - almost

a hundred of them are used for this critical job. Yet these same magnetic amplifiers

- the heart of the control system of one of the world's most up-to-the-minute fighting

machines-are straight out of the horse-and-buggy era.

Scores of magnetic amplifiers in the world-circling Triton control its atomic

reactor. Above, finishing touches are put on the General Electric "magnetic" that

monitors the reactor's temperature.

Forgotten and Rediscovered. Magnetic amplifiers came into being

when the century was just one year old. It would be six years - in 1907 - before

a youngster named Lee de Forest would make news with his audion, the world's first

vacuum-tube amplifier. And the transistor was still 47 years in the future.

For a while, it looked as though the magnetic amplifier would hold its own against

that upstart, the audion. In 1916, E. F. W. Alexanderson, the electronic pioneer,

employed magnetic amplifiers to modulate his early transmitters and many World War

I transmitting stations used his circuits. By the early 20's, however, the flashy

vacuum tube had taken over, and the "magnetic" was almost forgotten in this country.

Stages in the assembly of a magnetic amplifier. Its similarity

to a transformer in construction technique and general appearance is striking.

It was not forgotten in Germany, however, as we found out when World War II started.

In the years between the wars, the Germans had brought the magnetic amplifier to

a high state of development. War-time found them using magnetics for reliable, accurate,

and trouble-free control of everything from gun turrets to automatic pilot systems,

and they even used them in the V2 rockets.

Awakened to the possibilities inherent in this design, Allied scientists began

to push the development of magnetic amplifiers. Before much progress had been made,

though, the war was over. But the spark had been kindled, and a few years later

Vickers Inc. (now a division of Sperry Rand) came out with the first commercially

produced magnetics.

By that time, interest had been aroused all over the world. In the following

decade, hundreds of other firms, including all the big names in electrical and electronic

equipment, have added magnetics to their product lines. And almost no branch of

industry now operates without them.

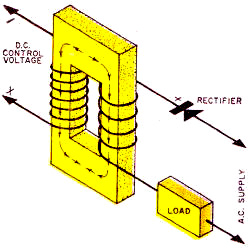

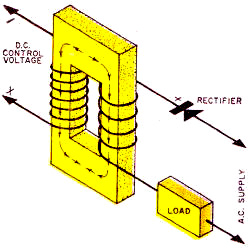

Flux Controls Current. A modern-day magnetic amplifier is, essentially,

nothing more than an iron core with two or more coils of wire wound around it. In

construction and appearance, it is similar to a transformer. But there the similarity

ends.

A magnetic amplifier - or saturable reactor, as it is sometimes called - is a

true amplifier. Like a vacuum tube, it uses a small signal to control a large one.

But there are sharp differences. Where the vacuum tube controls a current flowing

to a d.c. power supply, the magnetic amplifier controls an a.c. flow. While the

vacuum tube is primarily a voltage amplifier, the magnetic is a power amplifier.

And where the vacuum tube uses voltage variations to control a flow of electrons,

the magnetic amplifier controls current flow through a coil by varying magnetic

flux.

Fig. 1 - Basic circuit for half-wave magnetic amplifier.

Magnetic amplifiers like the Vickers unit above allow fingertip

control of elaborate lighting systems in TV studios. (NBC photo)

Thanks to magnetic amplifiers, this paper-making machine at West

Tacoma Newsprint Corporation in Tacoma, Washington, can operate at 5000 feet per

second, many times faster than previously possible. Magnetics continuously adjust

the speed of the take-up rollers, slowing them down as the roll of paper gets larger.

Control room.

Steel-rolling mills use magnetic amplifiers, too. Because the

steel gets longer as it is rolled, each set of rollers must turn at a slightly different

speed. Magnetics keep all the rollers operating at the proper speed relationship

regardless of how fast the steel is fed in. (Pittsburgh Steel photo)

Magnetics come in half-wave and full-wave types, as do a.c. power supplies. First,

let's look at the basic half-wave circuit shown in Fig. 1.A d.c. current

flowing through the control winding will cause a build-up of magnetic flux in the

iron core. The greater the flux, the lower will be the impedance of the output winding.

With a lower impedance in the circuit, more current will flow from the a.c. power

supply through the output winding and the load.

When the current in the control winding reaches a certain point, the core is

said to be saturated, which means that it has all the flux it can hold. At this

point, the impedance of the output winding is very low, and the current through

the load is very high. On the other hand, when there is no control current flowing,

and consequently no flux in the core, the output impedance is extremely high, and

practically no current flows through the output winding or the load. Thus, by controlling

the current through the control winding, the output winding impedance, and consequently

the current through the load, is made continuously variable.

A rectifier in series with the output winding keeps the constantly reversing

polarity of the a.c. supply from cancelling out the control winding flux. The direction

of the current flow through the secondary is arranged so that the magnetic fluxes

created by the two windings reinforce each other rather than cancel each other out.

Fig. 2 - Basic circuit for a full-wave magnetic amplifier.

A full-wave circuit is shown in Fig. 2. It works like the circuit in Fig. 1,

except that it makes use of both half cycles of the a.c. supply current. The two

halves of the output winding are wound so that the direction of the magnetic flux

created by both of them in the center leg of the core is the same as the direction

of the flux created by the control winding.

The bias winding can be used to control the general range of the amplifier's

operation, just as the bias on a vacuum tube causes the tube to operate on a certain

part of its characteristic curve. In a magnetic amplifier, when a small bias current

flows, a certain amount of flux is continuously present in the core, even with no

control voltage supplied. Thus, the impedance of the output winding will never reach

its maximum value, nor will the current through the load reach its minimum.

Many magnetic amplifiers have an additional control winding which is used for

feedback. This winding taps a certain amount of the output circuit's current and

applies it back as a control current. As with a vacuum tube, the feedback can be

either negative or positive. In general, negative feedback improves the linearity

of the amplifier while positive feedback increases its gain.

Single-stage magnetics can be built with gains of about 200,000, far beyond the

capabilities of the vacuum tube. With a gain on this order, a few milliwatts or

power in the control winding - an amount that could be supplied by one or two flashlight

cells - may control a load of 25,000 watts in the output circuit.

Rugged and Reliable. Magnetics are extremely rugged. They can

be - and frequently are - completely potted and sealed in airtight containers. They

thrive on extremes of heat, dust, moisture, vibration, and other adverse conditions

that would put vacuum tubes and transistors out of operation. Their efficiency is

high, as with transformers and other magnetic devices. In addition, no filament

current is required. So little heat is generated by magnetics that they can be packed

into extremely small containers which need practically no ventilation or cooling.

Because magnetics can handle large amounts of current easily, they are a natural

choice for electric furnace control. A Reynolds Aluminum Company furnace in Corpus

Christi, Texas, uses such a control system. Precise furnace control by magnetics

also helps to "grow" transistors in the latest types of transistor-manufacturing

processes.

Magnetics have recently begun to invade the field of entertainment, too. NBC's

two big color television studies - one in Burbank, California, the other in Brooklyn,

N. Y. - have magnetic amplifier lighting-control systems. With this setup, the lighting

man has fingertip control over each of the hundreds of lights throughout the studio.

He can control them individually or in banks, as he desires, working from a small

keyboard that looks something like an organ console. Unlike older types of theatre

lighting devices - autotransformers and rheostats-magnetics present no fire hazard.

Since magnetic amplifiers have no moving parts and no delicate components, they

last for years with virtually no maintenance. For this reason, they are used in

such critical applications as the control of the atomic pile in nuclear subs and

in missile-guidance systems, where reliability under adverse conditions of vibration,

heat, and acceleration is vital.

Reliability is also the reason magnetics were chosen to monitor and control the

critical voltages and currents of the transatlantic cable. If a voltage begins to

change, a magnetic compensates for the change, and, at the same time, sounds an

alarm so an operator can check to find the reason for the change. If the current

drawn by the underwater repeater amplifier tubes begins to rise, once again the

alarm is given, and corrective action is taken automatically. By insuring that the

current does not rise to dangerous levels, the magnetics prolong the lives of the

submerged tubes. This is important because lifting the cable to replace a damaged

tube costs thousands of dollars.

Long-Life Switching. Basic magnetic amplifier circuits can be

modified to give special effects. For example, a magnetic to which excessive positive

feedback has been applied becomes "bistable." This means that it is stable in only

two states of operation: maximum output or minimum output. There is no in-between.

The amplifier is adjusted so that the core is normally in a non-saturated state.

But even the tiniest input signal - perhaps only a few microamperes - will throw

it into complete saturation. Thus it becomes the equivalent of an extremely sensitive

switch, or relay.

But a magnetic amplifier is a switch without moving parts or contacts, and it

is virtually indestructible. The bistable magnetic is beginning to find widespread

use as a replacement for relays where long, reliable service is of great importance.

Several automotive companies - the Ford Motor Co., for example - are now using

magnetics to control the flow of parts in the engine assembly line. First, proximity

switches containing magnetic amplifiers sense the presence or absence of necessary

parts on an automated line. Other magnetics, cued by the proximity switch, supply

the parts as needed. Since there are no moving components and no contacts, these

magnetics show no signs of wear after millions upon millions of operations - long

after normal relay contacts would have worn out. Another series of magnetics controls

the speed of the engine assembly conveyor, to determine the proper production rate.

The uses for magnetic amplifiers are almost limitless. They serve as memory units

in computers and as speed regulators in steel, paper, and textile mills; they control

gun turrets and radar antennas on navy ships; they regulate the voltage output of

huge turbine generators; they control automatic elevators, mine hoists, power shovels,

cranes, and printing presses. In short, wherever the considerations of precise,

reliable, trouble-free control are important - from jet aircraft to atomic submarines

- you'll find magnetic amplifiers working silently and efficiently.

Posted January 5, 2022

(updated from original post on 10/21/2011)

|

The atomic submarine Triton glides swiftly and

silently through the deep. As its power plant purrs steadily, scores of electronic

watchdogs probe every part of the sub's powerful reactor. Suddenly the pressure

in a reaction chamber begins to rise over the allowable amount. One of the electronic

guardians instantly notes the rise and applies a corrective signal - before a human

operator could know that anything had begun to go wrong.

The atomic submarine Triton glides swiftly and

silently through the deep. As its power plant purrs steadily, scores of electronic

watchdogs probe every part of the sub's powerful reactor. Suddenly the pressure

in a reaction chamber begins to rise over the allowable amount. One of the electronic

guardians instantly notes the rise and applies a corrective signal - before a human

operator could know that anything had begun to go wrong.  The electronic watchdogs that keep the Triton's

powerful nuclear plant operating without a hitch are magnetic amplifiers - almost

a hundred of them are used for this critical job. Yet these same magnetic amplifiers

- the heart of the control system of one of the world's most up-to-the-minute fighting

machines-are straight out of the horse-and-buggy era.

The electronic watchdogs that keep the Triton's

powerful nuclear plant operating without a hitch are magnetic amplifiers - almost

a hundred of them are used for this critical job. Yet these same magnetic amplifiers

- the heart of the control system of one of the world's most up-to-the-minute fighting

machines-are straight out of the horse-and-buggy era.