July 1963 Popular Electronics

Table of Contents Table of Contents

Wax nostalgic about and learn from the history of early electronics. See articles

from

Popular Electronics,

published October 1954 - April 1985. All copyrights are hereby acknowledged.

|

"The boy and his father

had just witnessed a demonstration of one of the most promising and fastest developing

technological devices ever conceived by man - the laser. In only three whirlwind

years, the laser - which gets its name from the initials of Light Amplification

by Stimulated Emission of Radiation - has moved out of the theory stage, out of

the laboratory curiosity category, and into a whole new, exciting world of applications."

That's the opening of an article in the July 1963 edition of Popular Electronics.

I remember when ruby lasers were the the rule rather than the exception for lasers.

Power levels were measured in units of "Gillettes" in reference in the number of

razor blades they could cut through. Next came chemical lasers with power levels

in the megawatts and now even gigawatts that can take out ICBM warheads as they

reenter the atmosphere and can fry orbiting satellites. At the same time the realm

of semiconductors and microcircuits was turning out devices on the opposite scale

for use in communications, inertial navigation, and boardroom presentation pointers.

This article is an extensive recounting in layman's terms the state of the art in

1963.

Laser Status Report - One development follows another

in rapid succession

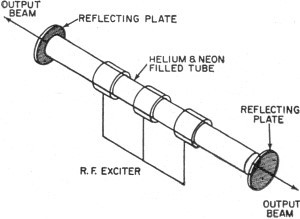

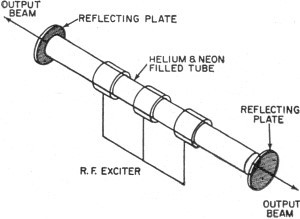

A c.w. gas laser recently demonstrated by Sylvania. An r.f. field

excites gas mixture to self-sustaining oscillation.

By Ed Nanas

The man behind the telescope-like device was ready. "I'll count down so you won't

miss the action," he said. "All set? Here we go - three, two, one, FIRE!" A pencil-thin

beam of red light shot out from a six-inch ruby rod less than a half-inch in diameter.

It smashed through a stainless steel plate as if the tough metal wasn't even there.

Then it hit a balloon suspended some ten feet away, vaporizing the rubber. And still

the beam of light continued on its narrow path, burning a small hole in a curtain

at the far end of the room. It was all over in a fraction of a second. "Wow! That

light sure packs a wallop!" exclaimed a teen-age radio amateur.

He was standing at the rear of the hall with his father, an electronics engineer.

"I've never seen anything like it!"

Until three years ago, nobody had seen anything like it!

The boy and his father had just witnessed a demonstration of one of the most

promising and fastest developing technological devices ever conceived by man - the

laser. In only three whirlwind years, the laser - which gets its name from the initials

of Light Amplification by Stimulated Emission of Radiation - has moved out of the

theory stage, out of the laboratory curiosity category, and into a whole new, exciting

world of applications.

The laser has the unique ability to generate and amplify light waves at specific

wavelengths just as radio waves are generated and amplified at specific wavelengths.

Light generated by a laser is known as coherent light because it is "pure," or predominantly

of one frequency. Making the sun seem like a hand-held flashlight by comparison,

the thin beams of coherent light, which have already vaporized steel and, in a recent

experiment, illuminated the moon, can be used to:

- Transmit a billion simultaneous telephone conversations on a single thread of

light one millimeter in diameter -without interference;

- Build laser radar systems, including portable range finders, having resolutions

more than 1000 times better than conventional narrow-beam radars;

- Perform micro-surgery - delicate eye surgery has already been demonstrated -

precise enough to allow cutting of a single human cell;

- Reach billions of miles into space with a beam powerful enough to guide a spaceship,

communicate with life on planets in other solar systems;

- Construct ultra-precise clocks, guidance systems, and laboratory instruments;

- Devise practical underwater communications and ranging systems using recently

developed techniques for generating green or blue coherent light;

- Build new battlefield weapons, including an anti-missile device and a form of

"death ray";

- Greatly speed up the functioning of complex computers by using lasers in conjunction

with fiber optic paths to transmit great masses of information within a computer

or from one machine to another;

- Investigate the possibility of transmitting electric power through space;

- Speed up chemical processes thousands of times, such as those that take place

during photosynthesis.

TV via laser is an accomplished fact. Image of the young lady

is relayed (in this experiment) to an optical modulator which impresses it on a

c.w. laser beam. The beam strikes a photocell in a telescope-like receiver (right,

rear) and is converted to the TV signal seen on monitor.

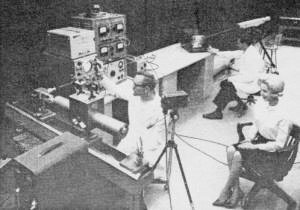

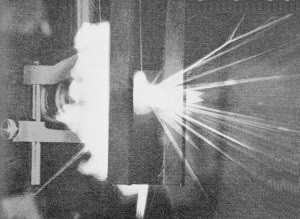

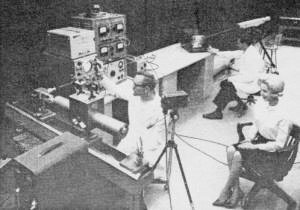

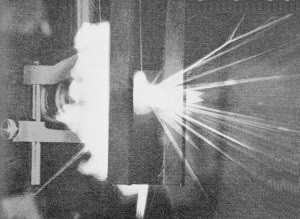

Highest power laser to date, the 350-joule Raytheon model may

soon be dwarfed by powers as high as 3000 joules. Intense beam of light is shown

blasting its way through a steel girder a quarter-inch thick.

Fantastic? Not at all; and the list is by no means complete. The laser is indeed

creating a revolution, and new discoveries relating to the generation and application

of coherent light are being announced almost daily. Let's take a closer look at

the phenomenon of laser light and the mechanisms used to generate it.

Coherent vs. Incoherent

Light waves coming from the sun or from incandescent or fluorescent lamps consist

of a broad band of frequencies all mixed together. In addition, light from these

sources can be considered as having been emitted from an infinite number of sources,

all of which have random phases and polarizations with respect to one another. We

call this kind of light incoherent.

A similar thing happens in the radio bands when lightning is discharged. A whole

host of frequencies are generated, and they can be heard as noise or static on a

radio receiver. As another example, incoherent water waves on the surface of a pond

can be created by throwing in a handful of pebbles; coherent waves by dropping in

a single large size rock.

Both a radio transmitter and a laser generate coherent radiation that is predominantly

of one specific frequency. The difference between the two is that the radiation

produced by the laser is very much higher in frequency (and, therefore, much shorter

in wavelength), so that it falls within the optical portion of the electromagnetic

spectrum.

The electromagnetic spectrum ranges from extremely low frequencies where wavelengths

(the distance between two specific crests or two troughs in a given wave) can be

measured in miles or meters, to frequencies far above the visible band where wavelengths

are measured in microns (one-thousandth of a millimeter) and angstrom units (one

ten-thousandth of a micron). In terms of cycles per second, light waves vibrate

at an extremely rapid rate - 1015 cps would be a rough figure.

t visible frequencies, radiation must be generated on an atomic level - as in

a laser. This is made possible by the fact that the atoms of certain materials,

when excited by large doses of energy, emit light at one frequency or group of frequencies.

Thus, a substance (ruby, for example) made up of atoms which can be excited, and

which will, at a certain point, emit coherent light, are used in lasers instead

of the electron tubes used at lower frequencies.

The Amazing Laser

The properties exhibited by laser beams are much more startling than the foregoing

explanation indicates. Like ordinary light, they can be focused and modulated, but

there the similarity ends. A laser beam, because of its extremely short wavelength

and because it is generated at the atomic level with all of the light energy in

phase, is a very narrow beam of extremely high energy. This energy, concentrated

at a single point, can burn through steel.

Continuous wave (c.w.) lasers have reached powers of 9 watts

and are expected to go higher in the near future. Many of these types use a dysprosium-doped

calcium fluoride crystal as does the RCA model below. The whole apparatus is enclosed

by two hemispherical mirrors which focus light on the crystal. The crystal itself

is obscured by the light source next to it.

The fact that a laser beam can be modulated is expected to be of great importance

in future applications. The reason is easy to understand. The transmission of a

voice by radio requires a band of frequencies several thousands of cycles wide.

The transmission of a television signal complete with sound takes up six million

cycles of the available spectrum. By and large, the radio portion of the spectrum

is now overcrowded, and the situation is expected to get progressively worse.

The use of optical frequencies for communications opens up great new vistas.

In the visible white-light portion of the spectrum alone, the number of frequencies

available is fantastic - 250 million megacycles! This figure represents thousands

of times more frequency space than in all the radio frequency bands combined. One

or two laser beams, relayed as microwaves are now, could carry all of the communications

traffic in America from coast to coast - telephone calls, television programs, computer

data, and facsimile!

Optical Powerhouses

The first successful pulsed optical maser (laser) generated a peak power of about

10 kilowatts for very short intervals. The newer lasers have now climbed much higher

- recently one was announced by the Korad Corporation with a peak of 500 megawatts

(500,000,000 watts) - all concentrated in one narrow beam of 7-nanosecond duration.

For the 500-megawatt pulse, it was calculated that the electric field in the focused

electromagnetic beam was on the order of 107 volts per centimeter. The

beam was observed

to cause ionization of the air in its focal path with a brilliant blue flash,

and spectacular damage was done to materials placed at the focal point. Since these

gigantic pulses of energy were for extremely short intervals, the total pulse energy

was only about 5 joules.

In only one year, the output energies of pulsed lasers have spiraled up from

1 or 2 joules (one watt for one second) to 350 joules. A thousand joules is just

around the corner and may be achieved by the time you read this. A glass laser with

a pulsed output of somewhere between 2000 and 3000 joules is under development by

American Optical Company, and may be announced as early as August, 1963. Theoretically,

there is no limit. Ten-thousand-joule-outputs are predicted within the next year.

What do all these figures mean? Just one joule - about the same amount of energy

you get from a flashlight bulb in several seconds of operation - is enough to vaporize

a hole through a 1/32-inch-thick sheet of steel if it is transmitted in a concentrated

burst of about a millisecond.

Sunlight pumping of a solid-state laser is a new development

which may soon make it possible to put sun-powered laser aboard satellites for communications,

tracking, and geodetic measurements. This device, designed by RCA, uses a 12" hemispherical

mirror to focus sun on calcium fluoride crystal rod.

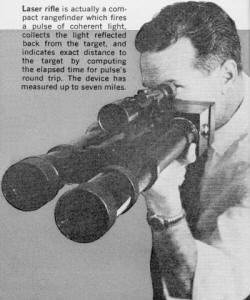

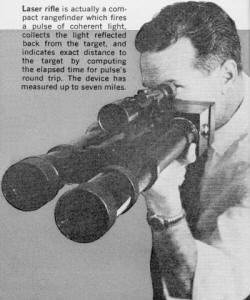

Laser rifle is actually a compact rangefinder which fires a pulse

of coherent light, collects the light reflected back from the target, and indicates

exact distance to the target by computing the elapsed time for pulse's round trip.

The device has measured up to seven miles.

A 10-joule ruby laser, which is fairly common today, operating at a wavelength

of 0.7 micron, has a power density at the center of the beam of about 1016

watts per square meter. The power density at the surface of the sun is less than

108 watts per square meter. Thus, this rather modest laser is capable

of producing a power density 100-million times that of the surface of the sun!

The Basic Laser

The essential ingredients of a laser are:

A Resonant Cavity

Usually formed by two reflecting surfaces, such as precisely parallel mirrors,

one slightly less opaque than the other;

An Active Medium

Positioned inside the cavity with its axis perpendicular to the reflecting surfaces.

It may be a (1) gas-a noble gas such as helium, mixed with neon, and contained in

a glass or a quartz tube; (2) crystal-a rod of high purity ruby, glass or a rare

earth material such as calcium tungstate; (3) liquid-an organic liquid, such as

benzene or pyradine; (4) semiconductor-the newest of the lasers, a gallium-arsenide

diode.

Pumping Power

Applied to the active medium to excite its atoms. It may consist of: (1) high-power

lamps - used with crystal lasers; (2) concentrated sunlight - also used with crystal

lasers; (3) electrical or radio frequency discharge - used with gas lasers; (4)

direct electric current - 10,000 to 20,000 amperes injected directly into the junction

of a diode laser.

The basic principles of laser light generation are similar to those of the microwave

maser. Atoms in the active medium can possess different amounts of energy. Ordinarily,

an atom will occupy the lowest of several energy levels, and is said to be in the

ground state. But when "pumping" power is applied, they get excited. That is, the

atoms absorb some of the photons (particles or "quanta" of light) from the power

source and jump to a higher energy level, like water being pumped into a tank atop

a standpipe.

At this higher energy level, usually two steps above the ground state, the atoms

begin to relax. They fall to an intermediate energy level, but still above the original

lowest level. This intermediate level is called the metastable condition, because

the atoms are more reluctant to leave it than they were to leave the higher level

to which they were originally excited. In order to make their departure they must

give up the light they absorbed. The important thing is that the light they give

up in dropping back to the ground state is of a specific wavelength.

Sooner or later, (within a few microseconds), the first atoms begin to drop from

the metastable level. They are put to work in the resonant cavity of the laser.

Without the reflecting surfaces, the light they emit would be mere fluorescence,

like that of a neon sign. But inside the resonant cavity of the laser, they are

bounced back and forth. With each pass parallel to the axis of the active material,

they stimulate other excited atoms in the metastable level to give off their absorbed

light much more quickly than they would ordinarily. The stimulated light moves in

the same direction as the light stimulates it. With each pass, the light gains more

energy in an effect akin to a chain reaction.

In only 200 microseconds or so, the released light waves, traveling in parallel

and in phase back and forth between the reflecting ends of the laser - you might

call it "feedback" - build up to an intensity great enough to escape through the

one end of the laser which is only partially opaque. This output beam of light has,

.most all of its intensity In a very narrow cone. All its waves are in step; of

the same phase and frequency, It is coherent light.

Basic configuration of a low-power c.w. gas laser. The reflecting

plates reflect back a large percentage of energy; result is a small, continuous

output.

A "Colidar" (for Coherent Light Detecting and Ranging), produced

by Hughes Aircraft Co., operates on the same principle as the laser "rifle" opposite.

Research is underway on other laser ranging devices.

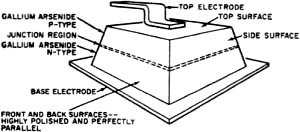

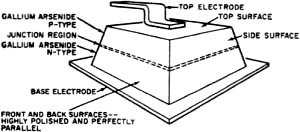

Gallium arsenide laser, greatly enlarged and shown in schematic

form, looks like this. Coherent light is emitted perpendicular to the front and

back surfaces and along the junction of device.

Continuous-Wave Lasers

A little over a year ago, the first crystal laser was made to operate continuously

(the high-power devices we have been discussing are pulsed) at Bell Laboratories

with power outputs of a few milliwatts. Gas lasers and semiconductor lasers also

have been made to operate continuously with comparative power outputs. As POPULAR

ELECTRONICS goes to press, however, a new 9-watt continuous-wave (c.w.) laser is

about to be introduced for use in research related to welding and other machine

tool uses.

A 45-watt c.w. laser may be another major development to be announced in 1963.

Both this unit, which is being researched at M.I.T.'s Lincoln Laboratory, and the

9-watt c.w. laser use dysprosium-doped calcium fluoride crystals rather than gases

or semiconductors.

Although c.w. lasers are somewhat puny in their power outputs compared to the

pulsed type, they have immense advantages as carriers for communications purposes.

At optical frequencies and with narrow beam angles concentrating all the radiated

energy into a small cone, a television channel could be established between the

earth and Saturn with only about 600 watts, while a voice channel to the most distant

planet, Pluto, could be maintained with as little as five watts.

Laser Status Report

Dr. Donald S. Bayley, of General Precision, Inc., one of some 400 organizations

conducting laser research, has said that an interstellar information channel carrying

one binary bit per second could be set up with the star Altair (16.5 light-years

away) with only 10 watts from a laser. Already, General Electric has designed a

burst communications system using a rapid laser pulse of great power (rather than

a continuous wave) to carry vast amounts of data.

Power Transmitters?

In the vacuum of space, attenuation is slight, governed primarily by the degree

of beam spread. Recently, Sperry Rand Corporation has been able to achieve the minimum

theoretical beam spread of a point source of light -0.005°, or 10-4 radians

- without the use of external lenses. Previously, the already narrow laser beams,

on the order of 0.05°, were further focused down by what amounts to an inverted

telescope.

The ultra-small beam spread of concentrated optical-frequency energy indicates

that it will be possible to transmit power over great distances with very little

loss; power for spaceships, for instance. It is now possible to construct optical

antennas, nothing more than a series of lenses, to transmit laser beams which would

lose only 1/30th of one percent in a 20-mile hop - far less than present-day transmission

lines. Thus, if you had a laser putting out one million watts, a hundred miles away

you would receive 997,500 watts: still quite a bit of power.

Laser Radar

One of the immediately attainable applications of the laser is in a radar-like

system for measuring distance and velocity, and for tracking. Several such systems

already have been built or are in the works, including those of Hughes, RCA, General

Electric, and Sperry. For example, the RCA tracking system, using a two-inch corner

reflector, is expected to achieve a range accuracy of six feet over 70 miles. The

Sperry system, using the Doppler effect, can measure the frequency shift of vehicles

traveling at 18,000 miles per hour, or as slowly as 0.2-inch per hour!

Such systems on the moon or in a satellite hold tremendous promise for guiding

spacecraft and rendezvousing in space. By 1965, laser radars are expected to provide

high-resolution maps of the moon and Mars, yielding new information about their

surfaces that will make landing a man a fairly safe procedure. A laser ranging and

telescope system will go into operation this year at Cloudcroft, N. M., to track

satellites such as the new Discoverer series; in that area of the country, the weather

is generally clear and lasers can be beamed into space from the ground.

Even the heavy-wheel gyroscope may be on its way out as a result of laser technology.

Sperry Gyroscope - the organization which invented the gyro - has come up with a

closed-circuit ring of lasers which can be used as an automatic device for guiding

ships, planes, missiles and space vehicles.

Brightest stars of recent research are semiconductor and liquid laser

devices.

Liquid "frequency converter" that can change the frequency or

color of a laser beam.

One of the first gallium arsenide lasers produced by G.E. (others

were made by I.B.M. and M.I.T.). It is suspended in liquid nitrogen to keep it cool

when large excitation currents are passed through it.

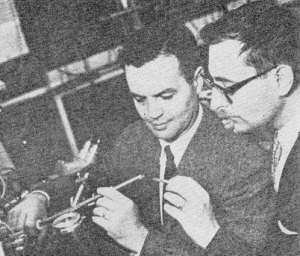

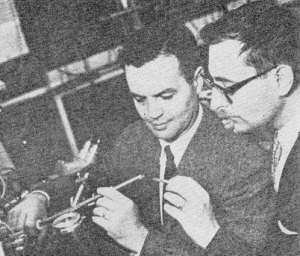

I.B.M scientists examine a brand-new semiconductor laser announced

very recently: an indium phosphide type.

New laser Types

One of the most important developments in the rapidly changing field of laser

technology came late last year when three organizations, I.B.M., General Electric,

and M.IT., announced almost simultaneously the development of a semiconductor laser.

The advantages of this type of laser-a gallium arsenide (GaAs) diode - are impressive

when compared to crystal and gas lasers. Semiconductor lasers approach efficiencies

of 100 percent as compared to a few percent for other types; they are excited directly

by electric current while other lasers require bulky optical pumping apparatus;

because they are excited by an electric current, they can be easily modulated by

simply varying the excitation current.

Gallium arsenide diodes (research models are already available as relatively

low-cost, off-the-shelf items) consist of a layer of p-type gallium arsenide and

a layer of n-type gallium arsenide. When electrons in an intense electric current,

about 20,000 amperes per square centimeter, are applied to the device, it emits

coherent or incoherent light, depending upon the diode type, from the junction between

the two layers of gallium arsenide.

Current research is concerned with improving the efficiency of semiconductor

lasers, modulating them, and, in a new twist, using them as "pumps" to improve greatly

the efficiency of other types of lasers.

Developed in a number of forms are lasers which use rare earth chelates - molecules

which completely enclose each atom of a rare earth element such as europium. Chelates,

combined with plastic, a liquid or other medium, can be pumped to produce laser

action.

One of the most important new laser techniques is a method for generating light

of different frequencies or colors from a single laser beam. By beaming coherent

light through a liquid such as nitrogen, light of other frequencies is obtained.

Laser frequencies can also be altered by heterodyning two beams by mixing them within

a crystal. These developments make it possible to convert intense laser beams to

any frequency; green, blue, or from far infrared to near ultraviolet regions.

Also within the year we have seen lasers operating at room temperatures rather

than having to be immersed in expensive cryogenic environments to keep them cool.

Lasers pumped by the sun, by cathode-ray fluorescence, and by exploding wires, as

well as by directly applied electric current, have come into being in the past twelve

months. Raytheon and M.IT. have bounced a laser beam off the moon. Whereas early

last year you had to build your own laser if you wanted one - an expensive and delicate

process even for the most advanced electronics engineer-you can now buy a wide variety

of laser types.

The Modulation Problem

While predictions on the future usefulness of laser beams in communications are

highly optimistic, much work remains to be done on developing practical methods

of modulation. Communications - including television signals - have already been

transmitted by laser in laboratory setups, but thus far, only a small fraction of

the fantastically large available bandwidth in a laser beam has been utilized.

The various approaches to modulation can be divided into two groups: internal

modulation applied while the coherent light is being generated, and external modulation

applied to the light beam after it leaves the laser. As we noted earlier, the gallium

arsenide laser is relatively easy to modulate using an internal technique. The excitation

current can be simply varied to produce modulation.

Another method of internal modulation, used with other types of lasers, involves

changing the Q of the laser cavity with an electro-optical shutter between the laser

material and a reflecting end plate of the cavity. This introduces a variable loss

which causes large changes in the level of operating power akin to amplitude modulation.

A third approach is Stark-effect modulation, achieved by sending a strong transverse

electric field into the laser material. This field causes line-splitting and frequency

modulation of the output. A similar technique, using a magnetic field, has also

been used. It is called Zeeman-effect modulation.

External modulation of the laser output can be accomplished using the Pockels

effect, in which the beam is passed through a piezoelectric crystal which can be

"strained" by an electrical field. Other external modulation approaches include

the Kerr effect (plane-polarization), varying the pumping power, and mechanical

means, such as the use of shutters, graings, lenses, reflectors and ultrasonics.

For demodulation, the radiation must be converted to electrical energy in most

cases. New phototubes, photomultiplier detectors, and photodiodes have been developed

for this purpose within the last six months. With coherent radiation, the same techniques

will work with light beams that will work with microwaves, so it boils down to a

difference in detail, not principle. Superheterodyne techniques can be used to convert

the light into lower frequency signals, such as microwaves; microwave detection

equipment can then be employed. "Heterodyning" is accomplished by "beating" one

laser beam with another. The result is a frequency equal to the difference between

the two falling in the microwave region.

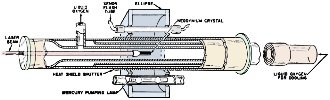

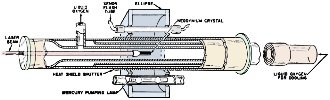

Continuous wave crystal lasers use configurations somewhat like

this Bell telephone design. The neodymium crystal is at one focus of a elliptical

cavity, and the mercury lamp at the other to concentrate pumping light.

Lasers, Present and Future

As indicated earlier, it isn't only the communications people who are taking

a close look at the laser. At Columbia-Presbyterian Medical Center in New York,

ophthalmologists already have used a ruby laser beam to coagulate a human eye retina

to prevent it from becoming detached. Such an operation can be com-pleted in less

than 0.001 second, eliminating the possibility of damage due to eye motion during

the exposure.

The machining and welding potential of the laser has already been demonstrated

in certain applications. At G.E., the surfaces of industrial diamonds have been

vaporized the instant the high-energy light beam strikes them. Production lines

are now being set up to use the laser beam in cutting "components" to size for use

in microcircuits, and to weld leads to semiconductors.

The laser also holds the potential of becoming

the ultimate anti-missile weapon. One proposal is to use high-power beams of several

lasers focused on the enemy missile with sufficient energy to vaporize it. This

would be a "clean" weapon compared to anti-missile rockets with nuclear warheads

and their attendant radioactive fall-out. The laser also holds the potential of becoming

the ultimate anti-missile weapon. One proposal is to use high-power beams of several

lasers focused on the enemy missile with sufficient energy to vaporize it. This

would be a "clean" weapon compared to anti-missile rockets with nuclear warheads

and their attendant radioactive fall-out.

A new laser scheme which theoretically could generate a billion joules or more

is under development now. It involves the separation and sorting of hydrogen spins,

the physics of which are too complex to go into in this article. Such a powerful

laser could transmit its beam through the atmosphere and earth cloud cover and still

deliver enough power at the impact point to vaporize a missile.

Power requirements could be sharply reduced, however, by orbiting an anti-missile

laser above the atmosphere. Laser light could also be used as a spotlight from space

for photography at long distances.

The laser is less than three years old, yet we have already come a long way.

The experts say that this is one field in which we are well ahead of the Russians.

To understand the laser is to understand an important facet of the future of communications,

medicine, machining for industry, and the practical equivalent of the legendary

death ray.

Whatever use the laser is put to, its impact on mankind will be great-comparable,

perhaps, to the discovery of atomic energy. When and how will the impact be felt?

Only time will tell.

Posted April 21, 2023

(updated from original post

on 1/16/2013)

|

The laser also holds the potential of becoming

the ultimate anti-missile weapon. One proposal is to use high-power beams of several

lasers focused on the enemy missile with sufficient energy to vaporize it. This

would be a "clean" weapon compared to anti-missile rockets with nuclear warheads

and their attendant radioactive fall-out.

The laser also holds the potential of becoming

the ultimate anti-missile weapon. One proposal is to use high-power beams of several

lasers focused on the enemy missile with sufficient energy to vaporize it. This

would be a "clean" weapon compared to anti-missile rockets with nuclear warheads

and their attendant radioactive fall-out.