|

July 1966 Popular Electronics

Table of Contents Table of Contents

Wax nostalgic about and learn from the history of early electronics. See articles

from

Popular Electronics,

published October 1954 - April 1985. All copyrights are hereby acknowledged.

|

With a fair helping of chagrin,

I admit to being a "10-4 Good Buddy" type of Ham radio operator. That moniker is

applied liberally by pre-1991 (February 14, to be exact)

amateur radio licensees to post-1991 licensees because that was the year in

which the FCC no longer required aspiring Hams to pass a Morse code proficiency

test for an entry level license (with restrictions). It was a sort of

Valentine's Day gift.

In 2003, the

International Telecommunications Union (ITU) announced the rescinding of its

code requirement and allowed countries to set their own standards. By 2007, General

and Extra exams no longer required code tests. I earned my Technician license in

2010, General license in 2015, and

Amateur Extra license in 2017 - all without sending or receiving a single dit

or dah (or keying a mike for that matter). Please don't hate me for it, because

I have every intention of learning code... maybe, if I ever get to retire, which

doesn't appear likely with the cost of living rising as quickly as it is :-(

How to Get the Most out of Your Key and Bug

As with a musical instrument, with practice

you can make the air waves sing As with a musical instrument, with practice

you can make the air waves sing

By Marshall Lincoln

If you operate in the amateur CW bands, you know that the sounds of the Morse

code sent by many hams bear only a slight resemblance to the precise signals sent

during the W1AW code-practice transmissions and those on your code records or tapes.

Many operators fail to observe proper spacing between letters in a word and spacing

between words.

IFYOUARELUCKYTHEIRSENDINGISASEASYTOREADASTHISLINEOFTYPE.

Other hams are apparently "rock and roll" fans. Some dashes are long; others

are short. One word is sent fast, the next word is sent slow; or their dashes are

sent at a sedate 10 wpm, but their dots rattle in your headphones at 30 wpm.

You have undoubtedly complained about these and other sending faults, but are

you sure that other hams aren't just as unhappy with your sending as you are with

theirs? Before denying such a possibility, you should tape a sample of your transmission

and then about a day or two later, listen to a replay of the tape. If you can copy

your own fist, chances are you are in good shape. But if it sounds like a lot of

garbage, or you swear that it isn't you, or that you think your tape recorder distorts

your signal, then you are eligible for membership in the fraternal order of Unfriendly

Fists Anonymous.

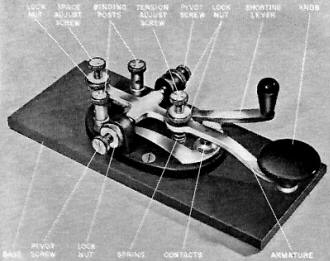

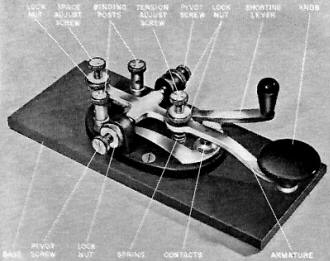

The more you know about the key, the more you will get to like

it. Adjust it properly. and treat it firmly, squarely and with authority. How you

adjust the key is largely a matter of preference, but there are some basic guide

lines to help you. See text.

Possibly, if all of us took a more critical look at our own sending, there would

be fewer unanswered calls. Let's briefly review the rules for good sending and take

off from there. Like a spoken language, the Morse code is a coherent combination

or grouping of sounds that make up a letter, word, or phrase. The letter "V" is

not just three dots and a dash - it's more like the opening bars of Beethoven's

Fifth Symphony.

Learn To Receive First. The experts generally agree that you

should first learn to receive before you begin to send. If you start using a key

before you know what good code sounds like, you're likely to form some bad habits

which you'll have to un-form later.

Where's a good place to find good code sounds? Probably the best is on the air

- from a station sending CW from punched tape. This "machine code" is usually perfect,

since it is untouched by human hands. Even if it's too fast for you to read most

of it, you should be able to catch enough characters to sense the rhythm, and proper

combination of sounds. Code practice records and tapes are also sources of good

sound, and they better serve your purpose because they start with slow speeds, say

2 or 3 wpm, and work up to speeds of 20 or 30 wpm, or more.

Once you have learned to receive at least 5 wpm, you are ready to hook up a key

to a code-practice oscillator and begin to learn how to send. The trick is to imitate

as closely as possible the perfect code you've been listening to. No one expects

you to measure off each dit and dah you send to be sure they fit a master plan,

or timing sequence of dots, dashes and spaces. Such a plan is illustrated above;

if you keep it in the back of your mind, it will help you considerably.

The length of the dit is the basic unit or time element. A dah is equal in length

to three dit's. Spaces between dit's and dah's equal one dit. Spaces between letters

in a word equal three dit's, and spaces between words equal seven dit's.

Key Adjustment. Your task will be easier if your key is properly

adjusted. A good rule of thumb recommended for beginners is to set the gap adjustment

screw on the key to obtain about 1/16" space between contacts. More experienced

operators prefer less spacing. The smaller the space, the less distance your fist

has to travel. But trouble begins and erratic and garbled sounds become the keynote

when the gap is made too small.

Spring tension should be adjusted to obtain comfortable but positive action.

If the tension is set too stiff, you will tend to clip your dit's and dah's;

they will sound staccato-like a machine gun, instead of like a rhythmic language.

Also, too much spring tension is likely to give you a quick dose of hand fatigue.

If the spring tension is too light, your characters will have a tendency to run

together.

Your Operating Position. There's an old axiom that says something

to the effect that if you slouch down in your chair, your code will automatically

become as sloppy as your posture. Sit up straight; not stiff as a ramrod, but comfortably

erect. Put both feet flat on the floor.

Rest your forearm, right up to your elbow, on the table, straight back from the

key. Not enough room on the table for that much arm? Then move things around so

that there is room. You're arm acts as a support for your wrist.

Your wrist is used as a lever, and it should not rest on the table. When in action,

it bobs up and down slightly. Most of the action takes place in the wrist itself,

causing your fist to move the most. Your fingers, once they grip the key, do not

move around as if you were playing the piano or a violin.

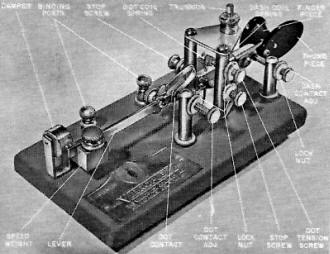

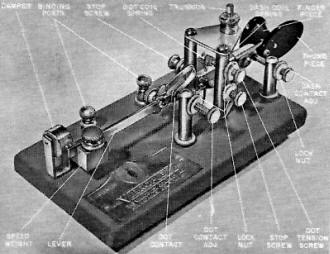

Is the bug a monster or your best friend? It depends upon how

well you are able to receive code. As with some musical instruments, you must listen

to the sound as you strum away - you may think otherwise, but you can't send faster

than you receive.

The right way to grip the key knob, like the right way to adjust the key, is

whatever way helps you to send good code comfortably. The way generally recommended

is to have your thumb, first finger, and middle finger surround the knob as shown

on p. 68. Your third and fourth fingers are allowed to rest in a relaxed position

curled partly into your palm. Your fingers grip the key gently, and at all times.

Keep your wrist flexible. Don't let it tense up. When you press down to close

the key, your wrist should spring up slightly. When your fingers come up with the

key, your wrist should move down. Sounds backwards at first, but with a little practice

you'll get the swing of it and find that it's quite comfortable.

Tips on Sending. Here are a few words of wisdom from the experts.

Don't rush your dit's. Keep the spaces between them the same length as the spaces

between the dah's.

Don't send choppy code, with the dit's and dah's clipped. Just let 'em roll out

at a smooth, even pace.

Don't force yourself to send fast. Your speed will build up gradually as you

get more practice.

Don't try to send faster than you can receive.

Do take pride in your sending. Your reputation will be no better than the quality

of your fist.

So You Want To Man a Bug. Well, there's certainly "no harm in

it. A lot of very capable operators do just that. But, don't rush this step like

too many fellows do. Don't believe that all hot-shot operators use a bug and you'll

never amount to anything if you don't use one too. It's awfully easy to make a pest

of yourself on the air with a bug if you don't know how to use one properly. As

a general rule, you shouldn't use a bug on the air until you are able to send and

receive at least 13 wpm.

Here's what the Air Force, in its tech manual on Morse code, says about sending

with a bug, "The bug is designed to make sending easy rather than fast, and perfect

control of the bug is far more important than speed."

A bug relieves you of the work necessary to form more than one dit in a sequence

of dit's. All you do is move the bug paddle to the right and hold it there. The

reed vibrates and whips out dit's like there's no tomorrow. When you get all you

need (and no more), you relax your touch on the paddle and the reed stops vibrating.

Dah's are fanned individually by moving the paddle to the left, and then releasing

it.

Posture and arm position are essentially the same as for a straight key. To move

the paddle left and right, roll your arm from side to side. This helps produce proper

rhythm and is less tiring than flexing the wrist or doing a jig with your fingers.

Working the bug is like playing certain musical instruments: you have to listen

to what you are doing.

Bug Adjustment. Like a fine watch, the bug must be properly

adjusted to work right. While the adjustment screws that bristle from all sides

of a bug can be set to please your own sense of touch and balance, there are some

general rules to follow. The Bell System, for instance, offers this advice:

(1) Adjust the back top screw until the reed lightly touches the deadener, and

tighten the lock nut.

(2) Adjust the front stop screw until the separation between the end of this

screw and the lever is approximately 0.015 inch, and tighten the lock nut. A greater

separation is permissible if you prefer more lever movement.

(3) Move the lever to the right, hold it in this position, stop the vibration

of the reed, and adjust the dit contacts until they just meet without flexing the

contact spring, then tighten the lock nut. This is a very important adjustment;

it should be checked after tightening the lock nut, to see that it has not changed.

Changing the position of the weight (which controls the speed of the reed), or

changing the tension of the retraction and dah springs, should not throw the bug

out of proper adjustment.

May your fist be as popular as a friendly handshake.

The main purpose of the bug is to make sending easier, not faster.

Posted July 13, 2023

(updated from post on 5/23/2018)

|