|

September 1975 Popular Electronics

Table of Contents Table of Contents

Wax nostalgic about and learn from the history of early electronics. See articles

from

Popular Electronics,

published October 1954 - April 1985. All copyrights are hereby acknowledged.

|

With the high

degree of computer automation at this point in time, it is doubtful that many

people still bother to perform digital logic simplification manually by using a

Karnaugh Map. Online apps like this one (KarnaughMapSolver.com)

do all the heavy lifting for you, producing minterms, maxterms, a truth table,

and a written-out Boolean expression. Back in the late 1980s when I was working

on my BSEE at UVM, the Karnaugh Map, created by Maurice Karnaugh,

of Bell Labs, was introduced in a digital electronics course. It was a fairly

easy concept to grasp. Is it taught in electronics curricula these days? This

1975 Popular Electronics magazine article provides a great introduction

to the Karnaugh Map. It appeared during the era where large scale integrated (LSI)

microcircuits were being widely designed into all forms of electronic products.

Karnaugh Maps for Fast Digital Design

By Art Davis By Art Davis

Have you ever tackled a digital design project with vim and vigor-only to find

yourself entangled in a morass of logic ones and zeros and a "this goes up, and

that goes down" nightmare? If you have, don't despair. There is a much neater, much

simpler method than the brute force approach. This article provides a coherent approach

to digital design. The method Is not a substitute for intuition and practical seat-of- the-pants experimentation, but a tool for getting the end results quickly.

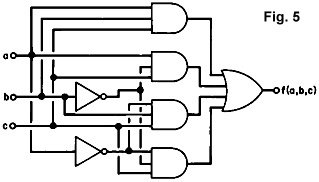

Before getting down to actual techniques, it might be wise to do a little reviewing.

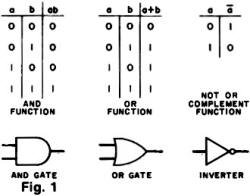

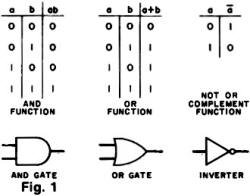

The truth tables for the AND, OR, and NOT (or COMPLEMENT, or INVERTER) functions

are shown in Fig. 1. The function a AND b is written ab; a OR b is written

a + b;

and NOT a is written a. Note that + as defined here is different from ordinary addition,

and merely symbolizes the function defined by the truth table of Fig. 1. A truth

table is simply an array, one side of which contains all possible combinations of

the input variables and the other side of which contains the corresponding values

of a logic function or output. Figure 1 also shows the digital logic gate symbols

for the three functions.

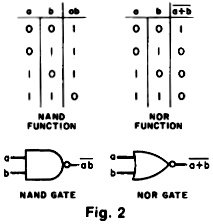

Any logic function can be constructed from these three

basic types of functions or gates. It is often convenient, though, when working

with a particular type of logic family (TTL, DTL, etc.) to use two other types of

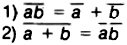

function, the NAND and the NOR. The NAND function of a and b is written ab, and

the NOR function, a + b. Their truth tables and logic symbols are illustrated in

Fig. 2. All of these functions except the NOT, or INVERTER, can be extended in an

obvious way to include more than two inputs. With these functions at hand, it becomes

possible to construct any logic function desired. Any logic function can be constructed from these three

basic types of functions or gates. It is often convenient, though, when working

with a particular type of logic family (TTL, DTL, etc.) to use two other types of

function, the NAND and the NOR. The NAND function of a and b is written ab, and

the NOR function, a + b. Their truth tables and logic symbols are illustrated in

Fig. 2. All of these functions except the NOT, or INVERTER, can be extended in an

obvious way to include more than two inputs. With these functions at hand, it becomes

possible to construct any logic function desired.

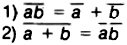

In manipulating the basic functions

to form more complex ones, it is expedient to have available two important, yet

simple, rules of basic logic theory known as DeMorgan's Laws. Figure 3 contains

truth tables for the logic functions ab,

a + b, a + b, and

a-b. Comparing them yields the formulas of DeMorgan's

Laws:

These formulas are useful in implementing digital functions using only NAND

or only NOR gates.

Why Map Techniques?

A truth table is one way of specifying a logic function - the Karnaugh map

(pronounced Kar-no) is another. To get an idea of what such a map is, and why it

is a convenient tool, let's look at a practical digital design problem. A truth table is one way of specifying a logic function - the Karnaugh map

(pronounced Kar-no) is another. To get an idea of what such a map is, and why it

is a convenient tool, let's look at a practical digital design problem.

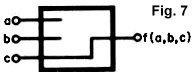

Suppose we are faced with designing the digital black box of Fig. 4, which

has three inputs a, b and c, and a single output f(a,b,c). The black box is to

provide a logic one output under the following input conditions:

a=b=c=1, a=c=1 and b=0, a=0 and b=c=1, or a=b=0 and c=1. How can we

manufacture the digital logic inside the box from this specification?

One possible answer is to be methodical. A person unfamiliar with map

techniques - but very methodical - might reason in the following way.

"The output function f(a,b,c) is logic one whenever a=b=c=1. An AND gate puts

out a one whenever all inputs are logic one, so let's use an AND. But the AND

output is zero for all other input combinations, and f(a,b,c) is a one for

several other input conditions.

"Well, the AND gate did pretty well for the first input combination, so why

not try it for the second? Let's take the complement of b by passing it through

an INVERTER and run it into an AND gate with a and c. This AND will put out a

one when a=c=1 and b=0, as desired. This seems to be working well, so let's do

the same with each of the other two combinations."

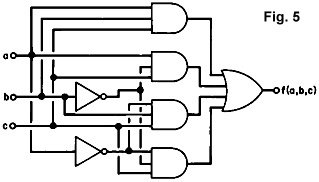

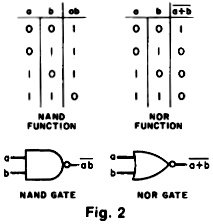

With all the AND gates and INVERTERs arranged as above, our methodical

experimenter will then observe that, since f(a,b,c) is to be a logic one

whenever the input variables form the first combination, or the second, or the

third, or the fourth, all he has to do is OR the outputs of the four ANDs to

generate f(a,b,c). The resulting logic is shown in Fig. 5. With all the AND gates and INVERTERs arranged as above, our methodical

experimenter will then observe that, since f(a,b,c) is to be a logic one

whenever the input variables form the first combination, or the second, or the

third, or the fourth, all he has to do is OR the outputs of the four ANDs to

generate f(a,b,c). The resulting logic is shown in Fig. 5.

Now this logic design works. It will do the digital job, but it is

inefficient. It requires four AND gates, one OR, and two INVERTERs. This is

costly, and it would cause quite a few layout problems because of the numerous

interconnections. In addition, the design procedure outlined above is slow and,

for more complicated circuits, error prone. What can be done to 'streamline the

procedure?

The answer is the Karnaugh map. This is just a rectangle divided up into a

number of squares, each square corresponding to a given input combination. The

Karnaugh map of our function f(a,b,c) is shown in Fig. 6. The right half of the

map corresponds to a=1, the left half to a=0 (a=1), the middle half to b=1, and so

on. The basic idea is that there is one square for each input combination. If we

write into that square the value of the output function for that particular

input combination, we will have completely specified the function. The ones and

zeros in Fig. 6 are the values which f(a,b,c) assumes for the associated input

variable combinations.

Now recalling our methodical design procedure, it is easy to see that each

square which has a one in it corresponds to the AND function of those input

variables, and f(a,b,c) can be generated as the OR function of all of the ANDs. Now recalling our methodical design procedure, it is easy to see that each

square which has a one in it corresponds to the AND function of those input

variables, and f(a,b,c) can be generated as the OR function of all of the ANDs.

A key factor arises here. It isn't necessary to include all of these AND

functions, and the Karnaugh map tells us how to eliminate some of the terms. For

example, looking at Fig. 6, we see that f(a,b,c) is a one for four adjacent

boxes forming the bottom half of the map. (We will consider squares on opposite

edges to be adjacent.) It is also easy to see the following: The only variable

which does not change as we go from one square with a one to another with a one

is c. It remains at one. What this means is that f(a,b,c) cannot depend on a and

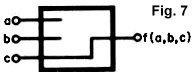

b because, regardless of their values, f(a,b,c) is a one as long as c=1.

Therefore we can forget about a and b, and implement our black box as shown in

Fig. 7. We have grouped together the four adjacent squares to eliminate a and b.

Notice that we have simplified things a great deal, since we now need no gates

at all. A key factor arises here. It isn't necessary to include all of these AND

functions, and the Karnaugh map tells us how to eliminate some of the terms. For

example, looking at Fig. 6, we see that f(a,b,c) is a one for four adjacent

boxes forming the bottom half of the map. (We will consider squares on opposite

edges to be adjacent.) It is also easy to see the following: The only variable

which does not change as we go from one square with a one to another with a one

is c. It remains at one. What this means is that f(a,b,c) cannot depend on a and

b because, regardless of their values, f(a,b,c) is a one as long as c=1.

Therefore we can forget about a and b, and implement our black box as shown in

Fig. 7. We have grouped together the four adjacent squares to eliminate a and b.

Notice that we have simplified things a great deal, since we now need no gates

at all.

Using a Karnaugh Map

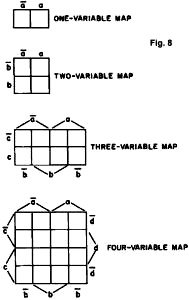

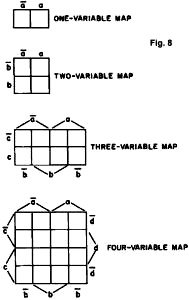

Maps of one, two, three, and four variables are shown in Fig. 8. Maps of one

variable are rarely used, and maps with more than four variables are seldom

needed - even if such a problem were to chance along, the Karnaugh map would not

be the tool to use. Its value depends on the pattern recognition capability of

the user, and it becomes hard to recognize pattern groupings in maps of more

than four variables. Maps of one, two, three, and four variables are shown in Fig. 8. Maps of one

variable are rarely used, and maps with more than four variables are seldom

needed - even if such a problem were to chance along, the Karnaugh map would not

be the tool to use. Its value depends on the pattern recognition capability of

the user, and it becomes hard to recognize pattern groupings in maps of more

than four variables.

Using the three-variable map as an example, note that there is one box for

abc, one for abc, another for

abc, and so on, with abc corresponding to

the input combination a=1, b=1, c=1; abc

to a=1, b=0, c=1; and abc to a =0, b =1, c =0; etc. Each box,

then, corresponds to a single row in the truth table. The map is arranged in

such a way that half of it corresponds to the uncomplemented form of a given

variable and the other half to its complemented form; and the variables are

interleaved so that every input combination corresponds to exactly one square,

and conversely. Usually only the uncomplemented form of each variable is written

- it being clear that the other hall of the map corresponds to the complemented

form.

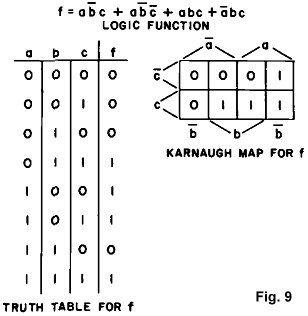

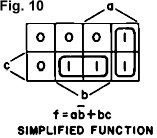

Now, a logic function is displayed by placing ones and zeros in the boxes on

the map. If a given input combination produces an output, or function value, of

one, a one is placed in the corresponding square on the map. If the output is

zero, a zero is placed in the square. As an example, look at the logic function

in Fig. 9. On the Karnaugh map, the box given by abc has a 1 in it. This means

that f is a logical one when the input variables have the value a=1, b=1, and

c=1. The box given by abc has a 0

in it. This means that f=0 when a=1, b=1, and c=0. These entries, as well as all

the others, can be verified by looking at the truth table. Now, a logic function is displayed by placing ones and zeros in the boxes on

the map. If a given input combination produces an output, or function value, of

one, a one is placed in the corresponding square on the map. If the output is

zero, a zero is placed in the square. As an example, look at the logic function

in Fig. 9. On the Karnaugh map, the box given by abc has a 1 in it. This means

that f is a logical one when the input variables have the value a=1, b=1, and

c=1. The box given by abc has a 0

in it. This means that f=0 when a=1, b=1, and c=0. These entries, as well as all

the others, can be verified by looking at the truth table.

The logic function in Fig. 9 is not at all simple looking. The question is,

how can the function be reduced to its simplest form? Variables can be

eliminated from the function by use of the following definition and rules:

Definition: Two boxes are adjacent if the corresponding

variables differ in only one place, for example if one box corresponds to a b c and the other to abc. Notice that

boxes on opposite edges of the map are adjacent under this definition.

Rule 1:

If two boxes containing ones are adjacent, the single variable which differs

between the two (uncomplemented for one, complemented for the other) can be

eliminated and the two boxes combined. These two boxes correspond to the AND

function of all the variables except the one eliminated.

Rule 2: If four boxes

containing ones are adjacent in such a way that each box is adjacent to at least

two others, these boxes can be combined and the two variables eliminated-those

two which appear in both complemented and uncomplemented form somewhere within

the group. The group of four corresponds to the AND function of all the

variables except for the two which have been eliminated.

Rule 3: The same

procedure holds for eight, sixteen, and so on, adjacent boxes. Each box in a

grouping must be adjacent to three, four, etc., others within that group. Rule 3: The same

procedure holds for eight, sixteen, and so on, adjacent boxes. Each box in a

grouping must be adjacent to three, four, etc., others within that group.

Rule

4: The various AND functions produced by the above groupings are "ORed" together

to yield the simplest function.

It should be noted that a given box can be

included in more than one grouping if that will simplify the overall function,

but each grouping should contain at least one box which doesn't belong to an

existing grouping (otherwise, this would lead to redundancy).

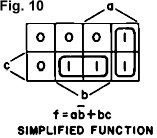

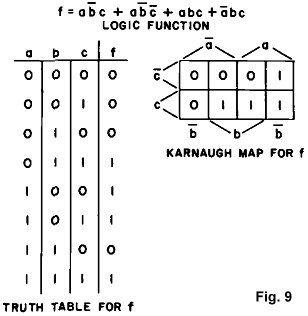

To illustrate, the Karnaugh map of Fig. 9 is repeated in Fig. 10, along with

the adjacency groupings and the resulting simplified function. Note the contrast

in simplicity. The boxes represented by abc and abc, although adjacent, are not grouped

together because each is already included in an existing grouping. Now we are

equipped to tackle a real -life problem. To illustrate, the Karnaugh map of Fig. 9 is repeated in Fig. 10, along with

the adjacency groupings and the resulting simplified function. Note the contrast

in simplicity. The boxes represented by abc and abc, although adjacent, are not grouped

together because each is already included in an existing grouping. Now we are

equipped to tackle a real -life problem.

BCD-to-Decimal Decoder

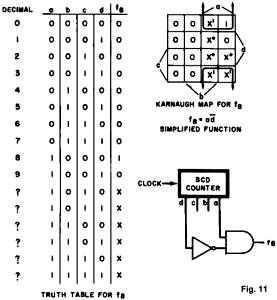

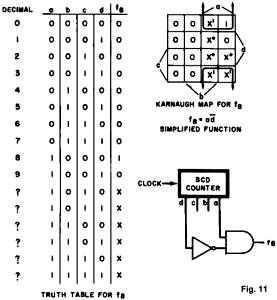

Consider the BCD counter of Fig. 11, with the four output variables a, b, c,

and d. Suppose we need to decode the count of decimal eight and provide a

control pulse, lasting one clock period, to some other digital circuit. We must

build a logic function defined by the truth table of Fig. 11. This truth table

introduces a new variable, called a don't care and given the symbol "X" The

don't care means that we can define the output function f to be either zero or

one for that particular input combination-simply because the input combination

will never occur. A BCD counter never counts above decimal nine. The X's can be

given values of zero or one so as to simplify the resulting function. In our

case, the don't cares have been chosen as indicated by the smaller ones and

zeros on the map. Notice the very simple form for the function f8, which can be

constructed from a single AND gate and an INVERTER.

The preceding was an example of what is called combinational logic. The

outputs at a given time are dependent only upon the inputs at that time.

Actually, the gates used to build up a logic function have some delay. In the

case of combinational logic, though, this just means that after the input values

are established, there is some flat delay before the output value is

established. The delay is critical only if we have to compare the output value

with another being similarly generated. If this is the case, we could encounter

problems with the timing margins.

In the digital game we are playing, though, the gate delays can be important

for a different reason. They allow us to build so-called sequential machines for

storing information, as well as for a myriad of other useful things. The general

idea of a sequential machine is illustrated in Fig. 12. All the gate delays of

delta seconds - for illustrative purposes only-are assumed to be lumped into the

output leads. The leads labeled x1, x2 and x3 are the external inputs, and those

tagged q1, q2, and q3 are the outputs. (There

could, of course, be any number of inputs and any number of outputs.) The leads

labeled Q1, Q2, and Q3, are assumed to respond

instantaneously to the inputs and fed-back outputs. In the digital game we are playing, though, the gate delays can be important

for a different reason. They allow us to build so-called sequential machines for

storing information, as well as for a myriad of other useful things. The general

idea of a sequential machine is illustrated in Fig. 12. All the gate delays of

delta seconds - for illustrative purposes only-are assumed to be lumped into the

output leads. The leads labeled x1, x2 and x3 are the external inputs, and those

tagged q1, q2, and q3 are the outputs. (There

could, of course, be any number of inputs and any number of outputs.) The leads

labeled Q1, Q2, and Q3, are assumed to respond

instantaneously to the inputs and fed-back outputs.

If the inputs have been in one state for a long time, the circuit will have

settled into a stable situation with q1, q2, and q3 identical with

Q1, Q2, and Q3, respectively. Now suppose one or more of the inputs changes values. Then no

longer will the small q's be the same as the upper-case Q's. After the passage

of (delta) time corresponding to the gate delays, though, the values of Q will

have propagated through to the outputs, and the small q's will again be

identical with the large ones. For a given set of input values, then, the small

q's are called the unstable states and the large ones the stable states of the

sequential machine. The feature which allows memory storage and other effects is

the regenerative characteristics created by the feedback.

The R-S Flip-Flop

An R-S flip-flop is a one-bit digital memory whose output is set to the one

state by a one on an input set (S) line and to the zero state by a one on

another line, called the reset (R). An incomplete truth table for this device is

sketched in Fig. 13. It is incomplete because the output stable state is

specified not only in terms of ones, zeros, and don't cares, but depends in

addition on the present (unstable) state q. We can form a complete truth table

by including q as one of the input variables, thus creating a feedback

situation. The complete truth table is also shown in Fig. 13, along with the

resulting Karnaugh map and the derived logic equation for the state Q. Note that

we must always have RS=0 (called the RS flip-flop constraint) to keep from

violating the condition that R=S=1 must never occur. Figure 13 also shows how

DeMorgan's Law is used to get the function into a form requiring only NOR gates

for its construction. By assuming all three possible combinations of input

variables (remembering the R=S=1 is disallowed from ever occurring) and

computing outputs, the truth table can easily be verified. It is also easy to

show in this way that the output labeled

Q is, indeed, the complement of the output labeled Q for all input

conditions except the disallowed R=S=1.

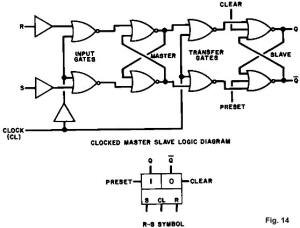

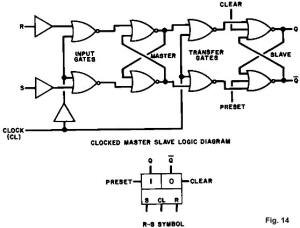

The Clocked R-S Master-Slave Flip-Flop

It is often desirable to have available an R -S flip-flop which changes state

only on, for example, the trailing edge (or 1-0 transition) of a clock signal.

It is possible to use the Karnaugh map to derive the form of such a flip-flop,

but the end result, although economical in number of gates and number of inputs

per gate, would not shed much light on the internal workings. It is often desirable to have available an R -S flip-flop which changes state

only on, for example, the trailing edge (or 1-0 transition) of a clock signal.

It is possible to use the Karnaugh map to derive the form of such a flip-flop,

but the end result, although economical in number of gates and number of inputs

per gate, would not shed much light on the internal workings.

This type of sequential machine is depicted in Fig. 14. When the clock goes

high, the R and S inputs are passed through the input gates and stored in the

master. When the clock goes low, the input gates are disabled, and the

information is coupled through the transfer gates into the slave flip-flop. The

function of the preset and clear inputs is evident. Try assuming a set of input

values for R and S, and trace the information flow, letting the clock change as

described above, to convince yourself that the unit performs the R-S function.

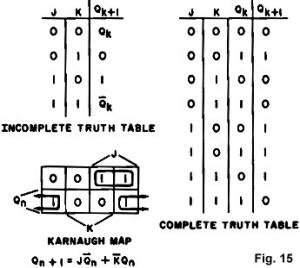

The J-K Flip-Flop

Let's return to our newly developed map technique now and develop the

(clocked) J-K flip-flop as a last example. For convenience, since output changes

are allowed only on clock transitions, let's denote the unstable state q by Qn

and the stable state Q by Qn+1. This is reasonable, because Qn

is the stable state just prior to the nth 1-0 clock transition, and is the

unstable state just afterward, with the flip-flop settling down into the stable

state Qn+1 before the next clock transition occurs. Let's return to our newly developed map technique now and develop the

(clocked) J-K flip-flop as a last example. For convenience, since output changes

are allowed only on clock transitions, let's denote the unstable state q by Qn

and the stable state Q by Qn+1. This is reasonable, because Qn

is the stable state just prior to the nth 1-0 clock transition, and is the

unstable state just afterward, with the flip-flop settling down into the stable

state Qn+1 before the next clock transition occurs.

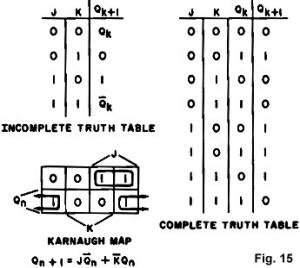

The incomplete and complete truth tables are shown in Fig. 15, along with the

Karnaugh map and the resulting simplified function. The J serves as the S and K

as the R, respectively, of an R -S flip-flop. The only difference is that the

J=K=1 output is now defined (Qn). The incomplete and complete truth tables are shown in Fig. 15, along with the

Karnaugh map and the resulting simplified function. The J serves as the S and K

as the R, respectively, of an R -S flip-flop. The only difference is that the

J=K=1 output is now defined (Qn).

Let's use the clocked R-S flip-flop to build the J-K from our derived

equation. For this purpose, let S=JQn

and R=KQn be the

inputs to the clocked R-S. According to the R-S equation,

Qn+1 = S + RQn

= JQn + (KQn)Qn

Now, applying DeMorgan's law to KQn,

we get

Qn+1 = JQn

+ (K + Qn)Qn = JQn +

KQn + QnQn.

But QnQn

= 0 always, so

Qn+1 = JQn

+

KQn

which is the J-K flip-flop equation.

Notice that the R-S constraint is satisfied, since

RS = (JQn)(KQn)

= JK(QnQn)

= 0

Fig. 16 shows the construction of the J-K from the R-S using two AND gates.

Again, test the operation by assuming a set of conditions for J and K

and tracing the logic flow. A glance back at the incomplete truth table will

reveal that if J=K=1 (J and K inputs tied to a logic one) the J-K forms a

toggle flip-flop.

The preceding examples have been intended to accomplish two things. In the

first place, knowledge of the logical operation of the various types of

flip-flops is essential in order to use them intelligently in an original

design. As a second objective, they have provided an effective demonstration of

the economy of thought which results when the Karnaugh may is used in a digital

design effort.

|

By Art Davis

By Art Davis

A truth table is one way of specifying a logic function - the Karnaugh map

(pronounced Kar-no) is another. To get an idea of what such a map is, and why it

is a convenient tool, let's look at a practical digital design problem.

A truth table is one way of specifying a logic function - the Karnaugh map

(pronounced Kar-no) is another. To get an idea of what such a map is, and why it

is a convenient tool, let's look at a practical digital design problem.  With all the AND gates and INVERTERs arranged as above, our methodical

experimenter will then observe that, since f(a,b,c) is to be a logic one

whenever the input variables form the first combination, or the second, or the

third, or the fourth, all he has to do is OR the outputs of the four ANDs to

generate f(a,b,c). The resulting logic is shown in Fig. 5.

With all the AND gates and INVERTERs arranged as above, our methodical

experimenter will then observe that, since f(a,b,c) is to be a logic one

whenever the input variables form the first combination, or the second, or the

third, or the fourth, all he has to do is OR the outputs of the four ANDs to

generate f(a,b,c). The resulting logic is shown in Fig. 5.  Now recalling our methodical design procedure, it is easy to see that each

square which has a one in it corresponds to the AND function of those input

variables, and f(a,b,c) can be generated as the OR function of all of the ANDs.

Now recalling our methodical design procedure, it is easy to see that each

square which has a one in it corresponds to the AND function of those input

variables, and f(a,b,c) can be generated as the OR function of all of the ANDs.  A key factor arises here. It isn't necessary to include all of these AND

functions, and the Karnaugh map tells us how to eliminate some of the terms. For

example, looking at Fig. 6, we see that f(a,b,c) is a one for four adjacent

boxes forming the bottom half of the map. (We will consider squares on opposite

edges to be adjacent.) It is also easy to see the following: The only variable

which does not change as we go from one square with a one to another with a one

is c. It remains at one. What this means is that f(a,b,c) cannot depend on a and

b because, regardless of their values, f(a,b,c) is a one as long as c=1.

Therefore we can forget about a and b, and implement our black box as shown in

Fig. 7. We have grouped together the four adjacent squares to eliminate a and b.

Notice that we have simplified things a great deal, since we now need no gates

at all.

A key factor arises here. It isn't necessary to include all of these AND

functions, and the Karnaugh map tells us how to eliminate some of the terms. For

example, looking at Fig. 6, we see that f(a,b,c) is a one for four adjacent

boxes forming the bottom half of the map. (We will consider squares on opposite

edges to be adjacent.) It is also easy to see the following: The only variable

which does not change as we go from one square with a one to another with a one

is c. It remains at one. What this means is that f(a,b,c) cannot depend on a and

b because, regardless of their values, f(a,b,c) is a one as long as c=1.

Therefore we can forget about a and b, and implement our black box as shown in

Fig. 7. We have grouped together the four adjacent squares to eliminate a and b.

Notice that we have simplified things a great deal, since we now need no gates

at all.

Maps of one, two, three, and four variables are shown in Fig. 8. Maps of one

variable are rarely used, and maps with more than four variables are seldom

needed - even if such a problem were to chance along, the Karnaugh map would not

be the tool to use. Its value depends on the pattern recognition capability of

the user, and it becomes hard to recognize pattern groupings in maps of more

than four variables.

Maps of one, two, three, and four variables are shown in Fig. 8. Maps of one

variable are rarely used, and maps with more than four variables are seldom

needed - even if such a problem were to chance along, the Karnaugh map would not

be the tool to use. Its value depends on the pattern recognition capability of

the user, and it becomes hard to recognize pattern groupings in maps of more

than four variables.

Rule 3: The same

procedure holds for eight, sixteen, and so on, adjacent boxes. Each box in a

grouping must be adjacent to three, four, etc., others within that group.

Rule 3: The same

procedure holds for eight, sixteen, and so on, adjacent boxes. Each box in a

grouping must be adjacent to three, four, etc., others within that group.  To illustrate, the Karnaugh map of Fig. 9 is repeated in Fig. 10, along with

the adjacency groupings and the resulting simplified function. Note the contrast

in simplicity. The boxes represented by abc and a

To illustrate, the Karnaugh map of Fig. 9 is repeated in Fig. 10, along with

the adjacency groupings and the resulting simplified function. Note the contrast

in simplicity. The boxes represented by abc and a

Let's return to our newly developed map technique now and develop the

(clocked) J-K flip-flop as a last example. For convenience, since output changes

are allowed only on clock transitions, let's denote the unstable state q by Qn

and the stable state Q by Qn+1. This is reasonable, because Qn

is the stable state just prior to the nth 1-0 clock transition, and is the

unstable state just afterward, with the flip-flop settling down into the stable

state Qn+1 before the next clock transition occurs.

Let's return to our newly developed map technique now and develop the

(clocked) J-K flip-flop as a last example. For convenience, since output changes

are allowed only on clock transitions, let's denote the unstable state q by Qn

and the stable state Q by Qn+1. This is reasonable, because Qn

is the stable state just prior to the nth 1-0 clock transition, and is the

unstable state just afterward, with the flip-flop settling down into the stable

state Qn+1 before the next clock transition occurs.