|

February 1959 Popular Electronics

Table of Contents Table of Contents

Wax nostalgic about and learn from the history of early electronics. See articles

from

Popular Electronics,

published October 1954 - April 1985. All copyrights are hereby acknowledged.

|

This 1959 Popular

Electronics magazine article reveals the pioneering spirit of early space electronics,

focusing on the X-15 rocket plane's inertial navigation system. The technology -

using gyroscopes, accelerometers, and stable platforms - was revolutionary for its

time, enabling precision guidance without external reference. The article highlights

innovations like wrist controls for high-G maneuvers (avoids moving heavy arms and

legs) and radar tracking networks, emphasizing the blend of human judgment and mechanical

reliability. Since then, technology has advanced spectacularly. Inertial navigation

has evolved into compact, hyper-accurate systems using ring laser gyros and fiber

optics, integral to everything from smartphones to interplanetary probes. Modern

spaceflight employs GPS, quantum sensors, and AI-driven autonomy, making the X-15's

achievements foundational yet primitive by comparison. We've moved from experimental

near-space flights to reusable rockets, Mars rovers, and satellite constellations

- a testament to seven decades of relentless innovation.

Electronics in Space

Electronics has the starring role in the

dramatic exploration of the last remaining frontier: outer space. North American

Aviation's X-15 rocket research plane, scheduled to be launched this month, will

carry a man for a few minutes to the fringe of outer space and beyond. Tremendously

powerful rocket engines will push the X-15 to fantastic speeds in the near vacuum

of space, but delicate microscopic electronic instruments will guide it surely and

deliberately on its journey. Electronics has the starring role in the

dramatic exploration of the last remaining frontier: outer space. North American

Aviation's X-15 rocket research plane, scheduled to be launched this month, will

carry a man for a few minutes to the fringe of outer space and beyond. Tremendously

powerful rocket engines will push the X-15 to fantastic speeds in the near vacuum

of space, but delicate microscopic electronic instruments will guide it surely and

deliberately on its journey.

Accurate navigation is all important in space flights, and with a man aboard

a rocket, no chances can be taken. Inertial navigation, which was developed for

our big satellite-carrying rockets, will be the guiding hand during the X-15's brief

brush with space.

Inertial Navigation

The principle of inertial navigation is as old as Newton's laws of motion. Inertia

is a resistance to a change in direction of motion, a resistance which can be measured

and used to guide a rocket or ship. It is independent of gravity, the earth's magnetism,

or radar. Inertial navigation was used to guide the "Nautilus" under the North Pole,

and it is an incredibly accurate system.

X-15 supersonic experimental airplane.

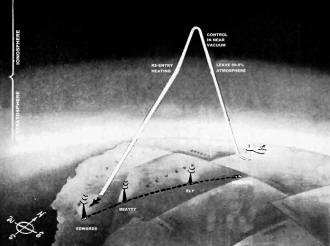

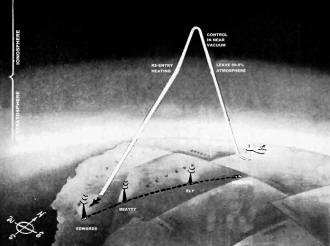

Flight path of the X-15 will carry it for a time into the near

vacuum of outer space. Three radar stations will track the spaceship from the moment

it leaves the "mother" plane until it lands at Edwards Air Force base.

Whether traveling through polar depths or stellar space, inertial navigation

is invulnerable to detection or jamming because it is completely self- contained.

It is independent of weather conditions or time of day or night, it is free from

altitude limitations, and it can be used anywhere in the world without referring

to the earth's magnetic field.

The X-15 will be launched from a B -52 "mother plane." Radar navigation devices

will compute its position until the exact moment of launch. From then on, it's on

its own and will navigate with a purely inertial system - completely without outside

aid. All that has to be known is the geographic location of the starting point and

destination - information which is set into the equipment's computer memory before

the plane leaves the ground.

Space Speedometers

The key to navigating inertially is the use of accelerometers, or "space speedometers."

These work on the principle of the pendulum. When the plane is accelerated, the

pendulum arm is displaced with respect to the plane.

The position of the arm can be measured and used to record changes in velocity

in any direction, including upwards. This creates an effective altimeter for outer

space. Conventional barometric altimeters which work by air pressure would be useless

in the upper limits of the earth's atmosphere and beyond.

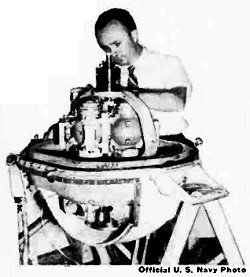

Stable Platform

As the accelerometers must be independent of the turning movements of the plane,

they have to be mounted on a "stable platform." The platform's stability is achieved

by a set of three gyroscopes and a gimbal suspension mounting. These serve to keep

the platform in the same spatial or angular relationship to earth no matter what

the heading or angle of the aircraft.

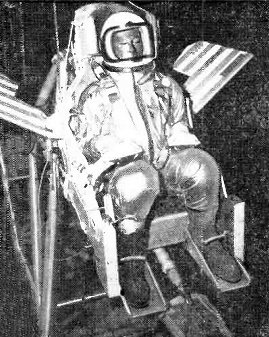

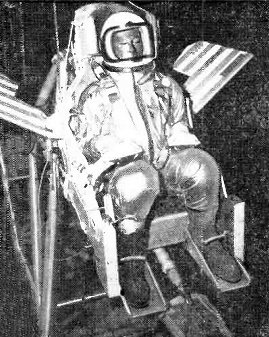

Wrist controls which pilot will use under severe acceleration

are being tested here. The supersonic ejection seat has foot clamps, arm guards,

and stabilizing fins to prevent spin.

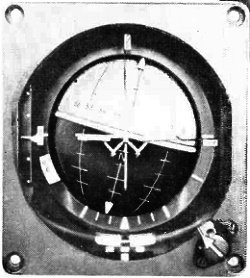

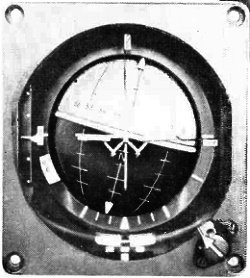

Sphere indicator tells pilot the angle of his plane with respect

to earth. A horizontal needle shows correct angle of attack to keep the plane from

burning up when reentering the atmosphere.

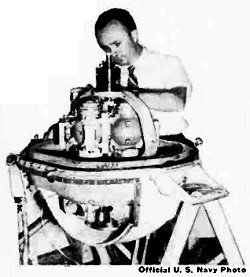

Stable platform is critical part of inertial navigation system.

It always points in same direction in space.

The accelerometers mounted on the X-15's "stable platform" will sense the acceleration

of the plane in any direction, and from this the altitude or angle of the plane,

its velocity, distance, and altitude can be computed. The platform is a marvel of

electronics miniaturization, and carries its own power supplies and amplifiers.

"Where Am I ?"

That's the question the pilot will be able to answer when his inertial navigator

gives him the facts. All the data on velocity and altitude and direction coming

from the stable platform and its computers will be digested by another lightweight

computer which will interpret it and display it to the pilot, helping him to stay

on a prearranged flight path.

A newly designed three-axis indicator will show the angle of the X-15 in relation

to the earth and will guide the pilot when his faster-than-a-bullet craft exits

and reenters the atmosphere.

Red Hot Plane

The X-15, which will fly at a speed better than one mile a second, will glow

red like a blacksmith's forge as it plunges back into the earth's atmosphere, hitting

a veritable "wall of air." The plane's longitudinal axis must be perfectly aligned

with its direction of flight when it reenters the earth's dense blanket of air.

If the plane enters the atmosphere too steeply, it will burn up, or if it approaches

the air layer at too shallow an angle, it will "bounce back" into space. To prevent

this, the pilot will have an "attitude sphere" in front of him which will give him

his angle of approach with regard to the earth in terms of pitch, roll, and yaw.

This instrument will receive information from the inertial navigation system.

The "attitude sphere" will give the pilot his precise position visually - so

that he can use his human judgment and selection, and command optional maneuvers.

In effect, the pilot is part of the guidance system - he is designed into the navigational

system as an extremely accurate and super-intelligent servo system.

Wrist Controls

Special controls will permit the pilot to keep the X-15 on course with wrist

motion only, because his arms will be pressed tightly into his seat by the tremendous

G forces to be encountered.

To keep the airplane pointing in the right direction while it is soaring above

the atmosphere, the pilot for the first time will bring into use the small hydrogen

peroxide jets located in the nose and the wingtips. Acting like jets of steam, they

will turn the plane in a direction opposite to their force, so that the plane reenters

the atmosphere nose first.

Tracking by Radar

Ground tracking stations must follow the flight of the plane, keep in constant

communication with it, and receive telemetered information. Since the plane's transmitter

is constantly moving, the highly directive antennas have to be kept pointing toward

the moving plane. To make sure that the antennas stay on target, an automatic tracking

facility is built right into the antenna system.

An ingenious system keeps the plane's signal centered right at the focus of the

parabolic antenna. If the signal goes off center, electric impulses are sent to

servo motors which rotate the antenna back into position. In addition, a computer

follows the movement of the antenna and computes the whole orbit of the flight,

adding its own correction to the antenna motion. The computer also keeps the antenna

tracking for about twenty minutes after the signal fades.

Usually several radar antennas are scattered over the length of the tracking

range. When one antenna finds the plane, it signals the other antennas so that they

can also find the correct position, even though their signal may be too weak, or

the plane over the horizon. The radio signals from all the antennas are combined

so that if one antenna loses the signal, another is still receiving it and relays

it to the control and communications center. In this way the plane's position is

always known, and telemetering signals, communications signals come through without

interruption.

As the X-15 soars into space, a thousand and one electronic instruments - radios,

computers, gyros, radar - will be watching, along with many anxious eyes.

|