|

October 1961 Popular Electronics

Table of Contents Table of Contents

Wax nostalgic about and learn from the history of early electronics. See articles

from

Popular Electronics,

published October 1954 - April 1985. All copyrights are hereby acknowledged.

|

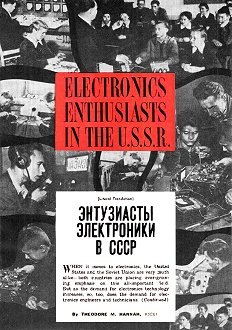

This 1961 Popular

Electronics article detailed the former Soviet Union’' state-driven

approach to electronics training, emphasizing government-sponsored youth

programs like "radio circles" and DOSAAF's militarized technical education. It

highlighted how the USSR centralized electronics innovation, controlling parts

distribution, publications, and amateur radio licensing to serve national

objectives. Considered oppressive and abhorrent by most U.S. citizens back in

the day, it is tragically ironic how the U.S. has adopted similar

socialist-communist models. The federal government now attempts to dominate

education through federally mandated STEM curricula and Department of Education

curricula, and state-controlled innovation hubs (CHIPS, the Science Act, etc.).

Private enterprise in technology has been suffocated by regulations, and

hobbyist initiatives are largely absorbed into increasingly government-regulated

(ham radio, model aviation, etc.) collective innovation programs. This mirroring

of Soviet-style central planning demonstrates how America has abandoned its

capitalist foundations for a top-down, state-managed technological future,

eroding individual liberty and perpetuating dependency on bureaucratic

oversight.

Electronics Enthusiasts in the U.S.S.R.

By Theodore M. Hannah, K3CUI By Theodore M. Hannah, K3CUI

When

it comes to electronics, the United States and the Soviet Union are very much alike-both

countries are placing ever-growing emphasis on this all-important field. But as

the demand for electronics technology increases, so, too, does the demand for electronics

engineers and technicians. How do the Russians satisfy this need ? What does the

Soviet government do to make sure there are enough electronics specialists to go

around ? And what part does the electronics hobbyist play in all of this?

Accent on Youth

To a greater extent than probably in any other country, the Soviet Union officially

encourages young people to become interested in electronics. It organizes electronics

courses (called "radio circles") in elementary schools and in the club houses of

the "Young Pioneers" (these are the youngest "members" of the Communist Party, ranging

in age from 9 to 14 years). It hires instructors and furnishes all the equipment

to teach youngsters - girls as well as boys - the Morse code and electronics fundamentals.

It requires such students to build and test simple receivers and other equipment.

And it encourages youngsters who show an aptitude for electronics to go into regular

electronics courses, which eventually lead to degrees in electronics engineering.

Training electronics technicians and radio operators in the Soviet Union is the

responsibility of a government agency known as DOSAAF (Voluntary Society for Assistance

to the Army, Air Force, and Navy). Headed by a Lieutenant-General in the Red Army,

DOSAAF claims to have a membership in the millions. And as a semi-military organization,

it sponsors not only electronics training courses, but rifle, parachute-jumping,

and motorcycle clubs as well.

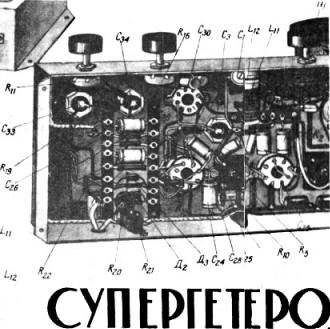

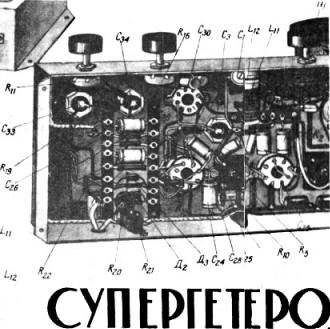

Pictorial and schematic diagrams appearing in Russian electronics

magazines are surprisingly similar to our own. Pictorial at top (only part of which

is shown) is for one of "three simple superhets" described in a recent issue of

"Radio;" lettering at bottom is portion of Russian word for "superheterodyne."

Schematic is of a receiver for hidden-transmitter hunts,

as Russian words at top explain. Note that resistors are ordinarily represented

by rectangles instead of zig-zag lines.

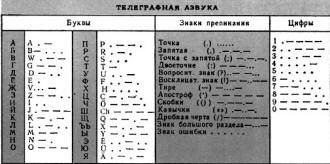

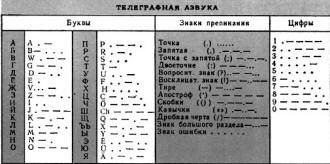

"Telegraphic alphabet" lists letters, punctuation marks, and

numerals. This chart is from a Soviet handbook and is the kind Russians use to learn

both the Russian and the International Morse codes.

In the electronics field alone, DOSAAF claims that more than a million persons

have completed its courses. And in addition to training electronics specialists,

DOSAAF also publishes electronics books and magazines, sponsors code-speed contests,

sets up exhibits, awards prizes for the best electronics construction projects,

and organizes ham radio contests of all kinds.

A new contest called "Radio Network Operating" is a good example of how the Russians

combine physical and technical training. The contest involves hiking cross-country

while carrying a 25-lb. load (the weight of a pack radio). At three different points

along the route the contestants stop, set up portable stations, and transmit messages

to each other. The whole contest is a race against time, with demerits given for

not completing the hike, setting up the stations, or handling messages in the time

allowed.

As part of this training, the Soviet government makes it as easy as possible

for hobbyists to get answers to questions on electronics. Any DOSAAF office anywhere

in the country will answer such questions, either in person or by phone. The same

is true of all Ministry of Communications radio centers. SWL's and beginning hams

can obtain technical help by mail from the Ministry of Communications in Moscow.

And there are even government offices set up to help hobbyists who are interested

in radio-controlled boats and planes.

As a matter of fact, if you should ever be in Moscow and find yourself stumped

by an electronics problem you might try calling the Central Radio Club-the phone

number is K-5-92-71!

Electronics Magazines

Among the most widely read of all Soviet publications are magazines dealing with

electronics. But with millions of Russians interested in electronics, no such magazine

remains on the newsstands for very long. On the other hand, small booklets on all

phases of electronics are mass-produced and sell for 10 to 15 cents apiece; written

for the beginner, they are widely read, particularly in rural areas where there

may be no regular electronics courses available.

The most popular of the Soviet electronics magazines (and the one most like POPULAR

ELECTRONICS) is called, not surprisingly, Radio (pronounced "Rahdio"). A monthly

publication, Radio sells for 30 kopecks (about 30 cents). It's published by the

Soviet Ministry of Communications and the DOSAAF organization which was discussed

on the previous page.

Every issue runs exactly 64 pages, no more, no less. And in those 64 pages will

be found a half-dozen construction projects dealing with anything from simple battery

radios to complex tape recorders and ham transmitters. Usually, there will be an

article or two on space exploration, too, with special emphasis on the electronics

equipment used in the space vehicles.

As a matter of fact, it was in the pages of Radio that the Russians revealed

the first advanced details of Sputnik 1. So that their radio amateurs would be prepared

to listen for Sputnik's signals, the Soviet government published the exact frequencies,

transmitting power, and type of signal to be used by the satellite. All of this

information appeared in the June, July, and August 1957 issues - as much as four

months before Sputnik caught the world by "surprise."

The average issue of Radio will also contain one or two articles on some new

Soviet receiver, TV set, or tape recorder. There will be at least one article on

the use of electronics in such fields as automation, cybernetics, or radio astronomy.

And for the ham and SWL, there is a column called "Chronicle," which reports on

DX activities around the world. Single-sideband is becoming quite popular among

Russian hams, and a column called "CQ SSB" reports on the latest in sideband techniques.

Another regular feature is a column called "From the Pages of Foreign Magazines";

here the Russian reader learns something about the latest developments in foreign

electronics, much of it translated from American magazines.

Obtaining Parts

Like most Soviet magazines, Radio contains no advertising. This raises an interesting

question: how does the Russian experimenter know what to buy and where to buy it?

As for what to buy, Radio and other magazines tell him what is available. As for

where to buy it, there is only one place - a government-owned electronics store.

Theoretically, there should be one such store in every town and more than one in

the large cities. However, even when this is the case-and it doesn't always work

out that way, there is still a problem in getting parts.

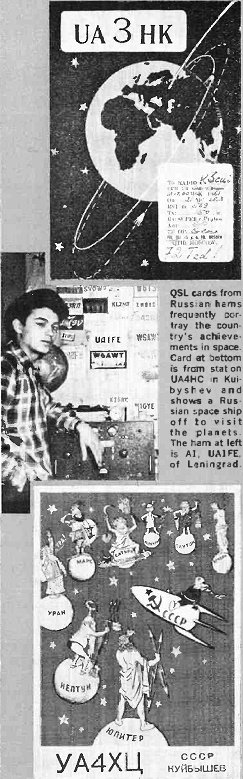

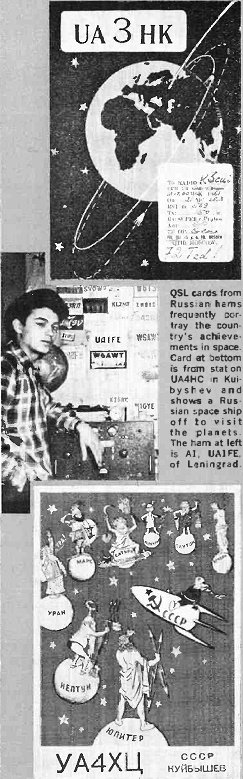

QSL cards. from Russian hams frequently portray the country's

achievements in space. Card at bottom is from UA4HC in Kuibyshev and shows a Russian

space ship off to visit the planets. The ham at left is A1, UA1FE, of Leningrad.

Radio quite often prints letters from readers who complain that their local parts

stores never have any parts! In this case, the electronics hobbyist can order parts

by mail from government-operated parts houses. And if that fails, about all he can

do is wait, hope, and write letters to Radio.

Actually, there is one other solution to this problem : the hobbyist can make

his own parts. This is particularly true of transformers, and construction articles

in Russian electronics magazines usually include transformer-winding data for the

Soviet do-it-yourselfer. Switches, tuning capacitors, coils, and even the mechanical

parts of tape recorders are also much more commonly homemade in Russia than here.

A few electronics kits are available, but only to hobbyists living in rural areas.

The kit selection includes a two-band receiver, a power supply, and a low-powered

transceiver, all of which can be ordered by mail from a government department in

Moscow.

Circuits and parts used by Russian hobbyists are not very different from those

used here - printed circuits, transistors, silicon diodes, and other relatively

new components are all familiar to the Russian experimenter. About the only difference

stems from the fact that Russian electronics parts are not as miniaturized as ours;

as a result, their equipment tends to be a little larger, and heavier than its American

counterpart.

Hams and SWL's

The Soviet government's involvement in amateur radio is much greater than is

the case in the United States. Like our Federal government, the Soviet government

issues licenses and regulates communications. But it also does much more. It aids,

encourages, and even subsidizes the ham and SWL by awarding prizes and medals to

winners in code -copying competitions, in hidden -transmitter hunts, and in national

and international DX contests.

Even QSL cards are available free from the government, although many hams and

SWL's design their own. Ever since Sputnik I, a favorite theme on Russian QSL's

has been the various Soviet space achievements. Some very handsome cards (and stamps,

too) have been issued on the Sputniks, Luniks, and cosmic rockets. The latest subjects

are, of course, Yuri Gagarin, Gherman Titov, and their manned space flights.

How does a prospective ham get a license? First, he must have completed a basic

DOSAAF electronics course. Then he takes an SWL test (in Russia the only officially

recognized SWL's are those who are licensed to listen on the ham bands). To pass

the test, he will have to understand basic electronics theory, wave propagation,

"Q"-signals, amateur operating procedure and lingo, log-keeping, the amateur frequencies,

international radio prefixes, safety rules, and first aid.

He must also send and receive Morse code-both Russian and International at a

minimum speed of 10 words per minute, and be able to build and repair simple receivers.

(As you can see, the Soviet SWL test is considerably more difficult than even our

Novice or Technician exams.) If he passes the test, he will be issued SWL call letters

(example: UA3-2791) and will begin listening on the ham bands at his local club

station.

After gaining some experience, he can take a test for a transmitting license.

For this he must be 14 years old, be able to handle code at 12 wpm, pass a tougher

examination, and build a transmitter.

There are two higher classes of licenses which are issued only after the applicant

has passed some very difficult tests, but these licenses offer some worthwhile privileges

(operation on all bands, 200 watts of power, and phone as well as c.w. operation).

The test for the first-class license, for example, includes a written exam similar

to that for our Extra Class license. The applicant must also send and receive code

at 18 wpm, design transmitter and receiver circuits, and be able to build and trouble-shoot

advanced transmitters and receivers.

The closest thing to the Citizens Band in the Soviet Union is a group of hams

who can operate only on the very high frequency bands (144 and 420 mc.). The minimum

age for these hams is 12 years and they needn't pass a code test; as in the U.S.,

maximum input power is limited to 5 watts.

There are no exact figures on the number of ham stations in the U.S.S.R., but

a reasonable guess might be 10,000 to 15,000. The number of individual hams and

SWL's is, of course, much greater many of the ham stations are club stations, each

of which has many operators and listeners. Radio magazine has announced that the

government hopes to have 25,000 ham stations on the air by the end of next year.

The precise number of electronics hobbyists is also unknown. But as long as Russia

needs electronics specialists and is willing to train hobbyists to become specialists,

we can assume that Russia's electronics needs will be met. From all accounts, we

can also assume that Russia's electronics technicians will be well-trained and competent,

the equal of any in the world.

|