|

August 1964 Popular Electronics

Table of Contents Table of Contents

Wax nostalgic about and learn from the history of early electronics. See articles

from

Popular Electronics,

published October 1954 - April 1985. All copyrights are hereby acknowledged.

|

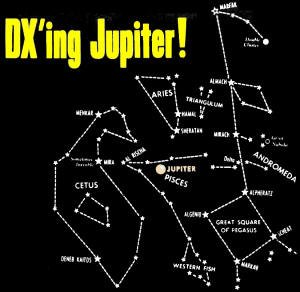

Out of curiosity, I asked AI when around the 1964 timeframe

Jupiter would have been in the position indicated map in the article - early in

the year it responded. I adjusted TheSkyX software until Jupiter appeared where

shown. That was late March - early April 1964. This image shows the two maps

juxtaposed for alignment. Cool, non?

This 1964 Popular Electronics magazine article captures radio astronomy's pioneering spirit when

Jupiter's radio emissions were still a novel discovery (first detected only nine

years earlier). Dr. Smith's work demonstrated remarkable accessibility - using

modified commercial receivers rather than specialized microwave arrays typically

associated with radio astronomy. The piece highlights key challenges of early

planetary radio research: navigating ionospheric interference, coordinating

multi-site observations for better resolution, and operating in crowded

shortwave bands. Researchers were still theorizing causes (cyclotron radiation

in Jupiter's magnetic field) and practical applications (space navigation, solar

flare prediction). The invitation for amateurs to participate underscores how

this field remained open to citizen scientists during its formative years,

relying on conventional equipment rather than massive institutional

infrastructure. Amateurs in both astronomy and amateur radio have contributed

significantly to the field of radio astronomy.

DX'ing Jupiter

Signals from outer space? It wasn't known until recently, but

the Giant Planet broadcasts signals any ham or SWL can monitor.

By Scott Gibson

One evening last summer, radio astronomer Dr. Alexander G. Smith of the

University of Florida tuned his Japanese pocket BC/SW receiver to 18 megacycles

and heard radio signals from the planet Jupiter. He was not surprised; Jupiter's

characteristic wide-band, surf-breaking-on-the-beach sound is easy to distinguish

from the narrow-band, fading-in sound of a distant phone station or the staccato

crash of earth - made static.

Dr. Smith has been studying Jupiter's radiations for nine years. He generally

uses Collins receivers and directional beam antennas, but on 21 that particular

night an unusually severe noise storm in the atmosphere - of the giant planet produced

signals strong enough to be readily detected even by a pocket radio with a short

whip antenna.

You can hear radio signals from Jupiter, too - with nothing more than an ordinary

amateur or SWL receiver and a good antenna!

It wasn't known until 1955 that Jupiter radiates low-frequency radio signals

of considerable intensity. Most radio astronomers search the microwaves with intricate

low-noise receivers and elaborate antenna arrays, but Dr. Smith's 23-man research

group is able to use conventional communications receivers and familiar-looking

beam antennas thanks, to the excellent signal strengths and low frequencies involved

- 5 megacycles and up. In fact, Jupiter's signal strength increases the lower you

go in frequency; above 15 mc, the energy falls off as the fifth power of the frequency!

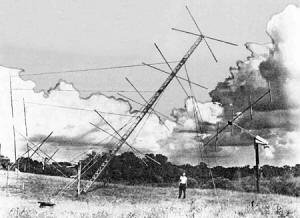

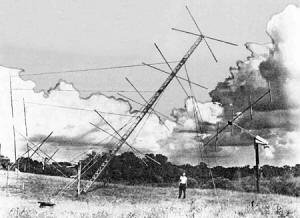

These familiar-looking antennas - from left to right, a corner

reflector, two four-element yagis mounted at angles and a five-element yagi - point

skyward toward Jupiter.

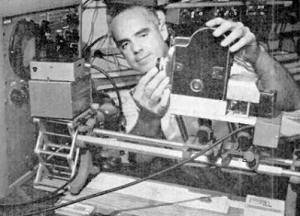

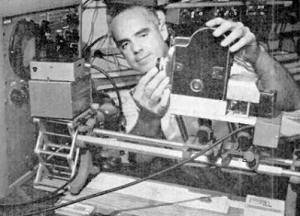

Collins and Hammarlund gear above - enough to delight any DX'er

- is connected to antennas at left for monitoring Jupiter's emissions from 5 to 30

mc.; Hallicrafters unit monitors WWV. Other equipment shown: three paper recorders

and a tape machine, all used to record Jupiter's signals for study.

Dr. Alexander G. Smith of the University of Florida's Radio Astronomy

Department adjusts 16-mm movie camera used to film Jupiter signals displayed on

scope screen of a panoramic receiver.

Although Jupiter's signals are heard in the very heart of the short-wave broadcasting

bands - Dr. Smith's group is currently observing 5, 10, 15, 16, 18, 20, 22, 27,

and 53 mc. - interference from earth-side stations is not as serious as you "might

expect from 15 mc. up, observations are made at selected hours of the night, usually

between midnight and dawn, when the sun-made ionosphere has thinned and no longer

deflects Jupiter's incoming signals. For the same reason, man-made signals are passed

on out into space rather than being reflected back down into the radio astronomer's

antennas. On the lower frequencies, however, the ionosphere never gets sufficiently

thin to pass out man-made signals, so the radio astronomers listen in the 10 kc.-wide-guard

bands on each side of W W V's carrier's. By international agreement these guard

bands carry no radio traffic-most of the time, anyway.

Even though QRM can be evaded on the lower frequencies, ionospheric deflection

of the incoming signals from Jupiter sets a limit on the lowest frequencies that

can be observed; below a critical frequency, the planet's signals are reflected

back into space. This critical frequency depends on both the density of the Ionosphere

and the angle between horizon, receiver, and Jupiter. If Jupiter is close to the

horizon, even 18-mc. signals may not get through; but if the planet is straight

overhead, much lower frequency signals are passed down to .'the receiving site.

Sunspots introduce another variable. The sunspots come and go in 11-year cycles.

During the sunspot maximum the ionosphere is much denser aid the lower frequencies

are blocked much more than they are at sunspot minimum. Since the next sunspot minimum

will occur is late 1964 or Early 1965, conditions are now good - and getting better

every day - for studying the lower frequency radiation from Jupiter.

Receiving the Giant Planet

The radio astronomers use ordinary Collins 75S receivers with the a.v.c. cut

off. For scientific reasons, three receiving areas are in action at the same time.

The main site is on the University of Florida campus and works directly with a second

site 35 miles away. In effect, these two antenna sites contribute to a common received

signal. Actually, the signals are photographed with high-speed cameras simultaneously

at both sites, and later the two images are combined from the negatives.

The two sets of antennas behave like segments of a radio telescope 35 miles in

diameter. In terms of resolving power, the results are as good as if you had a complete

radio. telescope of this diameter, although the amount of energy receives is much

less. The loss of signal is no problem, however, because the signals are very strong

stronger than any other extraterrestrial signals.

As both optical and radio telescopes are increased in diameter, it becomes possible

to get finer resolution of details, and Dr. Smith and one of his colleagues, Dr.

T. D. Carr, hope to be able to distinguish Jupiter's four separate radio sources

which have been predicted by statistical data.

The third station in the chain is located in Chile. In 1959, with the aid of

a grant from the National Science Foundation, a field station was built in Santiago

at the University of Chile to permit simultaneous observation of Jupiter from both

hemispheres. Because interference is not likely to occur in both hemispheres at

the same time, wasted observation time is minimized as much as possible, and if

there is a question as to whether a given signal is from Jupiter or just similar

sounding interference, the answer can usually be found by comparing records.

It is also possible that there are certain modifications in Jupiter's radiations

which might be caused by the earth's ionosphere and magnetic field; since the earth's

magnetic field is opposite in the two hemispheres, these effects can be sorted out

and it becomes possible to tell which are due to the radiation of the planet and

which are due to the earth's ionosphere and magnetic field. Because of more favorable

atmospheric conditions and less man-made interference. signals as low as 5 mc. can

be observed in Chile.

What Causes Radiation?

Since the earth's ionosphere is so reluctant to admit incoming low-frequency

signals, Dr. Smith has asked NASA to orbit a low-frequency receiver. This receiver,

circling high above the ionosphere, could record Jupiter signals that never reach

the earth's surface. An orbiting receiver might also tell us if radio-frequency

radiations are generated in the earth's own Van Allen radiation belts. Because the

earth's magnetic field is relatively weak, it is believed that any such radiations

would again be of too low a frequency to be passed through the ionosphere. The stronger

the magnetic field around a planet, the higher the frequency of planetary radiations.

On this basis, Jupiter's magnetic field is calculated to be ten times as strong

as the earth's. Study of the polarization of the received signals tends to confirm

this deduction.

Jupiter's radiations are far stronger than those of any other source except occasional

outbursts from the sun. Although Saturn is roughly the same size as Jupiter, it

is not yet certain that Saturn radiates at all in the short-wave bands; in any event,

the signals must be far weaker and less frequent. This lack of signals is possibly

due to Saturn's famous rings. They lie in the central plane of the probable magnetic

field and would tend to prevent the pole-to-pole circulation of particles, as must

occur in a radiation belt.

What causes this radio radiation and what significance does it have for us? Although

the exact cause is unknown, it is believed that the radio signals are the result

of "cyclotron radiation" emitted by solar particles trapped in Jupiter's powerful

magnetic field and spiraling back and forth just like the particles in the Van Allen

radiation belts around earth. These particles are spit out by the sun, part of the

outward flowing solar plasma. If this is true, then there must be powerful and dangerous

radiation belts around Jupiter just as there are around the earth, and space explorers

will have to be wary when in the vicinity of the planet.

The Jupiter signals may serve as guidance beacons some day. So far it has been

difficult to hit even the moon with a ballistic missile, demonstrating a great need

for guidance. Interplanetary explorers could use Jupiter's radio signals as a huge

radio beacon. Although the planet is not always "on the air," the transmissions

are frequent enough to be very useful as a means of correcting course during a long

flight.

Solar flares are one of the gravest dangers to space travelers. These are great

outbursts of radiation from the sun - unpredictable and extremely dangerous. If

some way could be found to predict the occurrence of these deadly radiation storms,

space travel would be much safer, just as ocean travel is much safer now that meteorologists

are able to predict the birth and movement of storms. There is evidence of a correlation

between solar flares and radio noise from Jupiter, and there is also a correlation

between the number of sunspots and radiation from Jupiter. Thus, there seems to

be some connection between solar phenomena and Jupiter's radio signals, so perhaps

the latter may be used as a means of predicting solar flares, just as approaching

terrestrial storms may be heralded by changes in atmospheric pressure.

Future research will include a study of the polarization of the Jupiter signals

which should give more information on the planet's magnetic field and the particles

it contains, plus an investigation of the curious spitting and popping signals occasionally

heard. These signals sound like the loud popping you hear when someone dials a telephone

in the next room and you have your receiver r.f. gain turned up high, and may be

due to the effect of our own ionosphere. A space satellite to be launched in the

near future will carry a transmitter radiating a 20-mc. c.w. signal. This known

steady signal will be compared with the Jupiter signal to see if the satellite signal

is broken up in the same way as the planet's signals occasionally are, thus giving

a clue to the effect of our own ionosphere on Jupiter's signal.

Interplanetary SWL'ing. If you would like to do a little interplanetary DX'-ing,

all you need is a reasonably good communications receiver and a good antenna. An

existing 14- or 21-mc. beam would be ideal, although a dipole will do, and even

a long-wire will bring in this DX when the signals are strong. You can readily identify

the Jupiter signals as described at the beginning of this article, and if you happen

to have a panoramic adapter, their 2- to 3-mc. wide envelope is easily distinguished

from the "spikes" of earthly radio signals.

Remember to consult your newspaper or almanac to learn approximately where in

the sky Jupiter is at the time. The higher overhead it is, the lower will be the

frequency of the signals coming through. The planet does not radiate continuously,

but only when one of its several noise sources is turned toward the earth, so a

little patience may be required.

The lower the frequency monitored, the more likely you are to hear Jupiter, for

both signal strength and rate of occurrence of outbursts are greater on the lower

frequencies.

Good DX!

|