October 1970 Popular Electronics

Table of Contents Table of Contents

Wax nostalgic about and learn from the history of early electronics. See articles

from

Popular Electronics,

published October 1954 - April 1985. All copyrights are hereby acknowledged.

|

Just as you will never get

everyone to agree on who was the first person to successfully fly a powered aircraft

(Wright vs. Whitehead vs. Curtiss vs. Gustave, etc.), there will never be a consensus

on who invented the radio. Most people would probably agree that it was

Guglielmo Marconi, but this author makes a case in the October

1970 issue of Popular Electronics magazine for none other than

Thomas Edison. I don't recall ever hear anyone making that claim

before, but before you dismiss the opinion, read on...

A Question of Semantics

Who Did Invent Radio? Who Did Invent Radio?

By Fred Shunaman

In all probability there will never be total agreement on the question of who

actually discovered radio. In fact, the word "radio" itself does not stand up to

a strict historical interpretation. Does the "first radio" mean the first two-way

wireless communication? Or a one-way wireless transmission? Or would a minor laboratory

demonstration and a patent establish the precedency of the discoverer/inventor?

In one way or another, Marconi, Popov, Loomis, Butterfield, Lodge, Hertz and

Tesla all qualify as discoverers of radio. However, history now shows that none

of these men has the supporting evidence of discovery that belongs to Thomas Alva

Edison-to whom the honor may rightfully belong.

A simple language difficulty may have cost Edison the credit for first discovering

and using radio as a means of communication. He announced the discovery of "etheric

force" when Marconi was only a year old and while Tesla was still attending school.

And, in 1885, two years before Hertz announced the discovery of electromagnetic

waves, Edison applied for a patent on a complete wireless system. Submitted with

his application were patent drawings of radio towers and antennas on the masts of

ships.

How It All Began. During the evening of November 22, 1875, Edison was studying

the action of a magnetic vibrator. He noticed a tiny spark between the armature

and core of the vibrator as the armature approached the core. Suspecting faulty

insulation, he checked the coil but found everything in order.

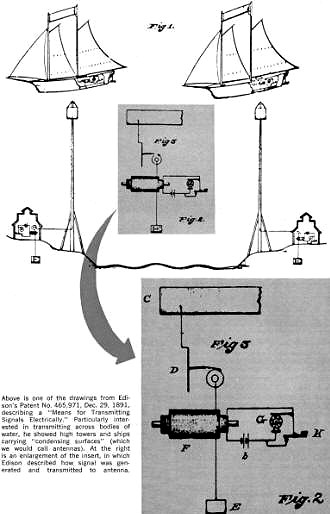

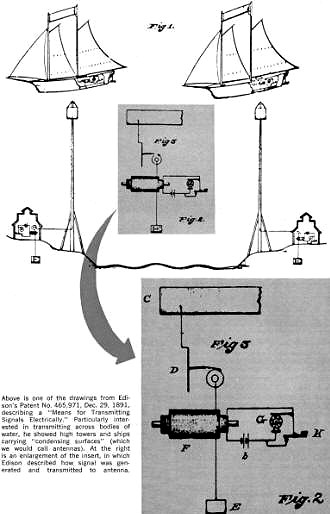

Above is one of the drawings from Edison's Patent No. 465,971,

Dec. 29, 1891, describing a "Means for Transmitting Signals Electrically." Particularly

interested in transmitting across bodies of water, he showed high towers and ships

carrying "condensing surfaces" (which we would call antennas). At the right is an

enlargement of the insert, in which Edison described how signal was generated and

transmitted to antenna.

Edison's "black box" 1881 demonstration had graphite points which

could be connected to an external circuit. The extension eye-shade permitted viewer

to see, jumping between the contacts, sparks unlike any known to an electrical phenomenon

at that period.

Thomas A. Edison, from a print dated 1877, about the time he

was working on his "etheric force" invention. This and other illustrations in this

article are adapted from those appearing in "Menlo Park Reminiscences," Vol. I,

by F. Jehl, Edison Institute, Dearborn Park, Mich.

However, Edison reported that; "If we touched any part of the vibrator we got

the spark," and that "the larger the body of iron touched to the vibrator, the larger

the spark." If a wire was connected between the vibrator and a gas jet on the wall,

a spark could be drawn from the gas pipes anywhere in the room.

Then Edison performed the experiment that Hertz was to do 17 years later; he

found that "if you turn the wire round on itself and let the point of the wire touch

any part of itself, you get a spark .... This is simply wonderful and a good proof

that the cause of the spark is not now known force."

Next, Edison constructed a demonstration apparatus and revealed his new etheric

force" to the Polyclinic Club of the American Institute. Many of the members seemed

upset by the name he had chosen for the new effect. But Edison was undaunted, and

he predicted (in the January 1876 issue of the Operator, a telegrapher's magazine)

that the new force might become the telegraphic medium of the future. He is quoted

as having stated: "The cumbersome appliances of transmitting ordinary electricity,

such as telegraph poles, insulating knobs, cable sheathings, and so on, may be left

out of the problem of quick and easy telegraphic transmission, and a great saving

of time and labor accomplished."

The Scientific American of December 1875 stated: "By this simple means signals

have been sent [by wire] for long distances, as from Mr. Edison's laboratory to

his dwelling house in another part of the town. Mr. Edison states that signals have

also been sent the distance of 75 miles on an open circuit, by attaching a conducting

wire to the "Western Union telegraph line."

As It Developed. A "black box," used by Edison to demonstrate etheric force was

sent to Paris where Edison's assistant, Charles Batchelor, lectured on the etheric

force. (The black box detector consisted of a pair of adjustable graphite points

in a shaded enclosure, with terminals to attach it to an external circuit.) There

is a bare possibility that Heinrich Hertz might have heard about Edison's experiments,

for hi spark points with the micrometer adjustment are virtually identical to those

in the black box, and he repeated the experiment of turning the wire back upon itself.

Work on the telephone took Edison's attention away from etheric force for some

time. But in 1885 he applied for a patent for a wireless telegraph system based

on his etheric force. The patent drawings show towers that are easily recognizable

as radio masts, and two ships with broad ribbon-like antennas hung between their

masts! The text of the patent application goes into detail about the equipment shown

in the drawings.

"The wire (from the 'condensing surface' C) extends through an electromotograph

telephone receiver D (Fig. 2) or other suitable receiver, and also includes

the secondary circuit of an induction coil F. In the primary of this coil is a battery

b and a revolving circuit-breaker G. This circuit-breaker ... is short-circuited

normally by a backpoint key K, by depressing which ... the circuit-breaker makes

and breaks the primary circuit of the induction coil with great rapidity," Edison

wrote.

Explaining the phenomenon as he saw it, Edison went on to state: "These electric

impulses are transmitted inductively to the elevated condensing surface at the distant

point ... "

Here is where the confusion in language occurred. At the time, the term induction,

unless otherwise explained, meant electrostatic induction (a tendency that still

lingers on in some elementary physics textbooks). The transformer had just been

invented, and magnetic induction was a laboratory curiosity. The term "electrostatic"

drifted into obscurity as the art progressed, and later writers referring to the

"induction telegraph" unquestioningly accepted the term to mean magnetic induction.

The confusion was increased because the only commercial use Edison made of his

invention was the "grasshopper telegraph," a system of telegraphing from moving

trains to the telegraph wires alongside the tracks. This was a distance that could

be covered easily by electromagnetic induction, and historians who believe that

radio communication started with Tesla, Lodge, and Marconi assumed that this was

the case. Yet, in explaining the "grasshopper telegraph" to a reporter, Edison said,

"The system works by electrostatic induction."

So, a change in the generally accepted meaning of a word with the changing times

buried the fact that Edison invented, described, patented, and operated a radiotelegraph

system in 1886 - a year before Hertz explained the cause of the etheric force, which

he called electric force.

What other "firsts" .may lay buried or attributed to other discoverers because

semantics denied the original inventor or discoverer his due? At least now Thomas

Alva Edison's long list of achievements will have numbered among them the discovery

of radio waves - even if he did not title them as such.

Editor's Note: We are given to understand that the graphic-points "black box"

is still in existence and has been exhibited on the second floor of the restored

Edison Laboratory.

In his book, "Menlo Park Reminiscences" (now believed to be out of print and

unobtainable), author Jehl says that Edison was intrigued by the spark and performed

many experiments to seek an explanation of its nature. Edison did find that the

spark was unpolarized; had no respect for the usual types of insulation; would not

discharge a Leyden jar; and had no effect on his electroscopes.

Unquestionably, Edison had stumbled onto radio-wave transmission, but the fact

that energy could be propagated through the atmosphere and not via wires was alien

to all of his telegraphy experiments.

|

Who Did Invent Radio?

Who Did Invent Radio?