|

September 1967 Electronics World

Table

of Contents Table

of Contents

Wax nostalgic about and learn from the history of early electronics. See articles

from

Electronics World, published May 1959

- December 1971. All copyrights hereby acknowledged.

|

Arthur Hackman's 1967

Electronics World magazine article provides a systematic guide for

selecting mechanical and manual switches, beginning with specifying the required

function through poles (circuits controlled) and throws (positions connected,

excluding "off"). Voltage and current ratings must not be exceeded to prevent

contact welding or catastrophic dielectric failure. Mechanically actuated

switches include pressure-sensitive types (with defined proof and burst

pressures), temperature-sensitive switches, and various limit switches (plunger,

lever, roller), which require consideration of mounting and environmental

sealing for harsh conditions. Manually actuated switches - push-button, rotary,

toggle, and slide - demand ergonomic design, including logical placement,

appropriate actuation force, and standard color identification (e.g., red for

urgent functions). The core principle is to use standard, commercially available

switches whenever possible, as most applications do not justify custom designs,

ensuring a balance of electrical capacity, mechanical actuation method, and

operator interface for reliable performance.

Switches - A Guide to Selection & Application

By Arthur F. Hackman By Arthur F. Hackman

Component Specialist,

Standards Engineering Dept., McDonnell Douglas Corp.

Important factors for mechanically and manually actuated switches are presented

as a practical aid in choosing the best switch for the job.

When trying to decide what switch to use, your first questions must be "What

function do I want the switch to perform? Will it be used to switch one circuit,

two circuits; to switch electrical power to one load, two loads, or to one of several

loads?" The answer must include the number of circuits and the number of loads,

or the number of poles and the number of throws which make up part of the switch

description. The word "throw" is not to be confused with the word "position" since

"position" includes any "off" position that may exist. Hence a simple single-pole,

double-throw switch can switch the power of one circuit to either of two loads and

may be equipped with two, or with an "off," three positions. If a switch is to be

kept in some particular position, this too is reflected in the description, such

as single-pole, single-throw, normally open. Standard terminology and circuit arrangements

are illustrated in Fig. 1. Those for rotary and other types of switches will be

covered later in this article.

Fig. 1 - Popular contact configurations and circuit terminology.

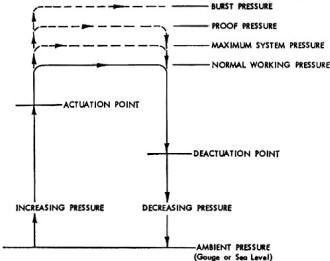

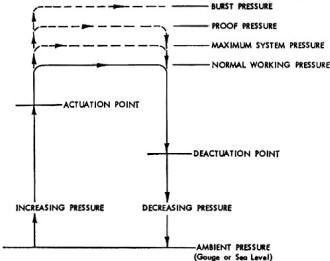

Fig. 2 - Schematic operating cycle of a gauge pressure switch.

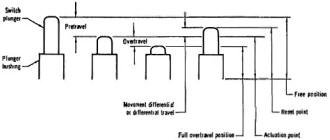

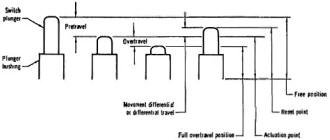

Fig. 3 - Terms describing operation of limit switches are shown.

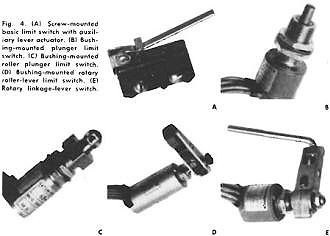

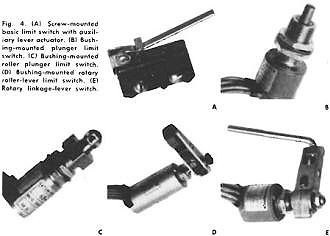

Fig. 4 - (A) Screw-mounted basic limit switch with auxiliary

lever actuator. (B) Bushing-mounted plunger limit switch. (C) Bushing-mounted roller

plunger limit switch. (D) Bushing-mounted rotary roller-lever limit switch. (E)

Rotary linkage-lever swatch.

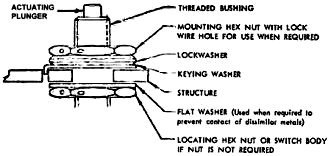

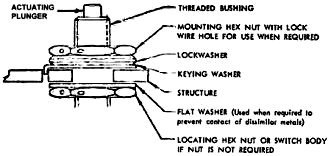

Fig. 5 - Accepted installation of a bushing-mounted switch.

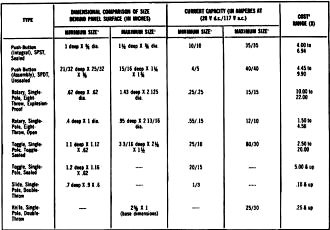

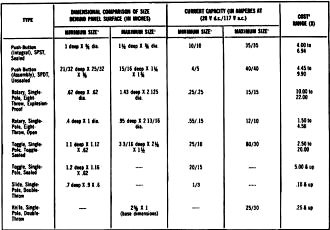

Table 1 - Comparison of manually actuated switches with their

main advantages and limitations.

Table 2 - Characteristics of a cross-section of available manually

actuated switches of various types.

Fig. 6 - (A) Push-button assembly. (B) Integral push-button.

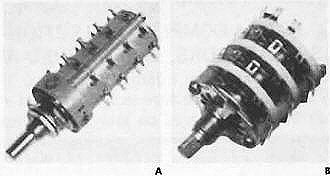

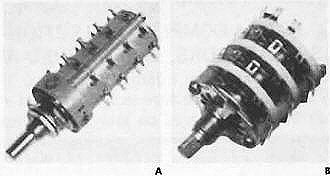

Fig. 7 - (A) A typical explosion-proof rotary switch is shown

here. (B) More common open rotary switch.

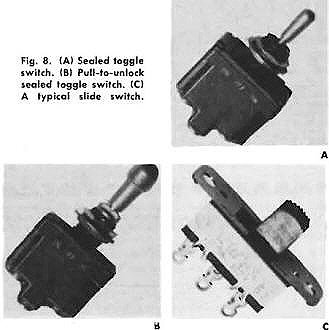

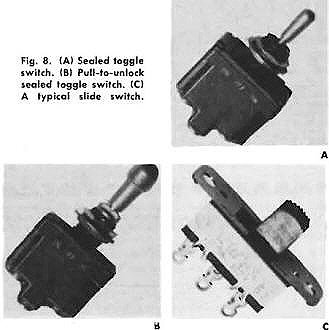

Fig. 8 - (A) Sealed toggle switch. (B) Pull-to-unlock sealed

toggle switch. (C) A typical slide switch.

Voltage and current ratings must also be considered. The electrical ratings of

the switch should not be exceeded if satisfactory operation is expected. It is not

necessary to derate or use a percentage of the rated current of the switch of a

reputable manufacturer. However, if greater electrical life is desired, the manufacturer

can probably recommend a reduced current that will increase switch life. Current

overloads decrease switch life: sufficiently high or consistent overloads cause

early switch failure by welding the contacts. Over-voltage also decreases switch

life. Ultimate switch failure from overvoltage results because the switch is unable

to interrupt current flow after the contacts have separated. Voltage or dielectric

failures are usually catastrophic, sometimes resulting in an explosion.

Often, minimum levels of voltage-current are overlooked but when values are expressed

in millivolts and microamperes it is wise to determine and specify the maximum acceptable

voltage drop at the rated load across the contacts. Usually gold contacts are specified

for such applications, but this should be checked with the manufacturer or your

company's switch specialist, if there is one.

There are many advantages in using off-the-shelf switches. The fact is that the

vast majority of applications can be handled without the need for a specially designed

switch. Admittedly, the state of the art would never advance without new designs,

nevertheless an attempt should be made to use existing switch designs whenever and

wherever possible.

After determining what circuit configuration and electrical capacity is required,

the next choice involves the method of actuation. This choice falls into two categories:

1. mechanically actuated, and 2. manually actuated switch.

Mechanically Actuated Switches

Very often an engineer will find that the mode of mechanical actuation is dictated

by his design, that is, the medium sensed is also the actuating medium. The majority

of these switches fit into the following categories: pressure sensitive switches,

temperature-sensitive switches, and position-sensitive or limit switches. Pressure-sensitive

switches are used when specifications require changes in fluid pressure to be monitored

or controlled. Switches are available to cover a wide range of pressures - from

those of over 25,000 psi to pressures expressed in fractions of an inch of mercury.

Generally speaking, the actuating mechanism of pressure switches incorporates a

pressure -sensitive diaphragm coupled to an electrical switch. Actuation of the

switch occurs within a specified range of pressures. Similarly, deactuation occurs

within a specified range of pressures. This range includes the actuation (or deactuation)

point plus a tolerance which will vary widely, depending upon the accuracy required

and the pressure range of the switch. Good engineering practice demands that only

the required accuracy be specified as the tolerance, not the best available. The

deactuation point is the pressure at which the switch mechanism resets and, as a

general rule, occurs at a lower pressure than that which caused actuation. Sometimes,

the terms of actuation and deactuation are interchanged, depending on the primary

application of the switch in question.

The proof pressure is the maximum pressure that can be applied without a calibration

shift in the actuation and deactuation points. Good design requires that the proof

pressure of a switch be a minimum of one and a half times the maximum system pressure.

The burst pressure of a pressure switch is the maximum pressure to which the

switch can be subjected without rupture or damage. Usually, burst pressure is two

to two and a half times the pressure in the system under normal operating conditions.

Fig. 2 shows schematically an operating cycle of a gauge pressure switch and

illustrates the terms just discussed. The different types of available pressure

switches include: 1. altitude or 48 absolute pressure switches, 2. differential

pressure switches, 3. vacuum switches, 4. altitude switches, and 5. absolute pressure

ratio switches.

Temperature-sensitive switches are used to protect against over -temperature,

indicate an extreme temperature, or control at a specified temperature. The characteristics

and behavior of thermal switches are similar to those of simple pressure -sensitive

switches except that they are operated by changes in temperature. Actuation and

deactuation occur in a similar manner. They are available with ranges from -100

°F to +500 °F. Switches with smaller ranges are also available with tolerances approaching ½°F.

The range of the switch is a function of application, and tolerance or temperature

differential will depend on the accuracy required.

Limit or position-sensitive switches are used to actuate or deactuate equipment

relative to cam position or door location. Very often limit switches are multicircuited

to actuate signal lights to indicate the condition of the equip - Silent. Types

of limit switches vary according to the type of actuation, including lever, plunger,

roller plunger, rotary roller-lever, and rotary linkage-lever, and non-contacting

switches. Non-contacting or remote sensing switches perform the same function as

other mechanically actuated switches but without physical contact. These include

proximity, photovoltaic, photoelectric, or pneumatic devices acting as sensors coupled

with amplifiers or relays to perform the switching functions. Since their use is

largely confined to automated machinery, they will not be discussed here.

Plunger-actuated limit switches allow the greatest range of applications, but

are restricted to inline actuation with controlled overtravel. If the overtravel

is not controlled, the switch may be damaged if the force is sufficient. (The actuation

point of bushing-mounted plunger switches can be set by means of the two hex nuts

supplied with the switch. Often, due to the normal build-up of tolerances, the exact

position of actuation cannot be predetermined. It is then necessary to adjust the

nuts by a cut-and-try technique to locate the exact actuation point of the switch.)

Operating characteristics applying to limit switches are shown in Fig. 3.

The most popular mounting means are: 1. bolt or screw-mounted as in Fig. 4A or

2. bushing-mounted as in Fig. 4B through E. The bolt or screw-mounted limit switch

is essentially restricted to basic switches, with most sealed limit switches being

bushing- mounted. Sealed limit switches can be designed to operate in almost any

environment. They are often watertight to the extent that moisture cannot be pumped

into the switch through cycles of pressure or temperature with the resultant condensation.

Some sealed switches, for example, are subjected to environments that build up ice

on the actuating plunger. An integral part of the switch, called the "ice scraper,"

acts to clean the plunger upon actuation and free it of ice. If the switch has been

held actuated and the actuating force is removed, the release force built into the

switch acts to break the ice barrier.

Lever actuation is most often employed with a basic switch, as shown in Fig.

4A. Advantages include its compact size, ease of installation, general lack of tight

tolerances, and its flexibility of application with additional actuators. Its main

disadvantage is its vulnerability clue to a lack of protection.

A roller-plunger limit switch is a slight modification of the plunger limit switch

(Fig. 4B) for adaptation to cam or slide actuations which have an incline or rise

of less than 30 °. An example is shown in Fig. 4C. Often the roller plunger has

an adjustment mechanism that allows locking the roller in 45° increments. Cam or

slide actuation with an incline of more than 30° requires a rotary roller-lever

actuation, the type shown in Fig. 4D. This type of actuation usually operates in

only one direction and is spring-loaded to return the lever to a neutral or deactuated

position after the operating force is removed.

A modification of the rotary roller-lever switch is the rotary linkage-lever

(Fig. 4E) which is used to physically connect the actuating device to the switch.

This switch operates in both directions but has no return spring. The linkage-lever

is threaded so it can be attached to the actuating device which must provide the

deactuating as well as the actuating forces. The actuation point of both rotary

lever switches is positioned by a worm gear with a screw adjustment that locates

the arm in any position through 360°.

Mounting of rotary-lever switches is often similar to that of plunger switches

except the axial positioning of the switch is not as critical and, for this reason,

only hex nut is used. Fig. 5. shows an accepted method of installing a bushing-mounted

switch. Note that the keying washer is placed on top of the structure to serve the

dual purpose of keying the switch and protecting the structure from the lock washer.

An alternative to the keying washer, as used by some switch manufacturers, takes

the form of two tabs projecting above the switch body which engage two mating holes

in the mounting. In areas of extreme vibration, a lock wire is used to prevent loosening

of the mounting nuts.

Manually Actuated Switches

A selection of manually actuated switches offers the designer a little more leeway

in his circuit than mechanically actuated switches. Personal preferences may sometimes

influence switch selection since a goodly number of applications can be handled

by more than one type of switch. Table 1 compares applications while Table 2 compares

parameters of a number of different manually actuated switches.

The application of a manually actuated switch simply conveys a message from the

man to the machine. The man/ machine concept involves several considerations. Since

the design of the machine interface is the more flexible, the switches involved

must be selected and applied to fit the operator. The considerations involved are:

1. physical location, 2. mode of actuation, and 3. identification of the switch.

Actuating levers and knobs that are most often used should be in close proximity

to the operator's normal position. The switch in the control panel should be positioned

so that the operator's clothing won't accidentally cause actuation. The switch should

also be located so that it is not inadvertently actuated. If this is not possible,

protect the actuator with a guard. Ideally, if several switches are mounted on a

single panel, they should be spaced far enough apart to avoid accidental actuation

of a switch due to its proximity to another.

Consideration should also be given to the environment in which the switch will

operate. Even though performance, life, and reliability can almost always be increased

by improved sealing, this often carries a prohibitive price tag. For this reason,

economics usually dictates selection of the least amount of sealing that can do

the job. In addition to the obvious case of selecting a sealed switch if water may

drip or splash on it, a sealed switch should also be selected if it will be exposed

to extremes of temperature or some other environment that might cause moisture to

penetrate the switch when the environment is a non-operating one. Flexible rubber

seals or boots are available to aid in sealing a switch between the actuator and

mounting bushing and/ or mounting panel.

The mode of actuation should be consistent with habit reflexes, e.g., actuate

a toggle in the upward of forward direction to bring machinery up to full speed,

or push a button to test for some condition. The effort required for actuation may

sometimes be related to the switch application. For example, when switches will

be actuated at high speeds and for long durations, a light actuating force is recommended.

It is also desirable that some form a feedback, an indicating light for example,

be designed into the circuit if the switch does not provide some audible or operational

indication of actuation. Assuming the switch is in working order, the positive "snap"

of actuation or sudden reduction of operating force will often be sufficient evidence

of actuation.

Printed or lettered identification of the switch should be within reading distance

and numbers or letters associated with the switch should be located in such a way

as to allow reading when the operator is in his normal position. Sometimes an unusual

shape of a knob or handle may be employed to help the operator make the proper selection

quickly, but this type of design is generally not recommended as it relies on the

operator's memory.

The majority of manually actuated switches fit into the following four categories:

push-button switches, rotary switches, toggle switches, and slide and knife switches.

Push-button switches are of two general designs: either a basic switch (or switches)

mounted in a push-button housing, Fig. 6A, or an integral push-button switch, Fig.

6B. The switching chamber of the first design is simply that of the basic switch,

often enclosed but unsealed. The integral push-button switch has a housing that

is usually water-sealed at the plunger and environmentally sealed at the terminals.

Both groups are further subdivided into lighted and unlighted push-buttons, with

several possible identifying colors available. Unlighted push- buttons should be

colored black. Lighted push-buttons should be red, green, amber, white, or blue.

Requirements for the application of identifying colors as indicators are as follows:

Red: The circuit controlled by the switch requires immediate attention, e.g.,

a portion is inoperative or corrective action must be taken.

Green: The circuit controlled is in satisfactory condition, e.g., the equipment

is within operating tolerance.

Amber: The circuit controlled is in a marginal operating condition, caution may

be required.

White: The circuit is operating satisfactorily with no "right" or "wrong" implications.

White is often used to convey some additional information to the operator.

Blue: Blue is used to indicate radiation hazards but is generally accepted as

an alternative to white. Blue should be used only when absolutely necessary since

it doesn't show up well.

Push-buttons are available with maintained actions and momentary actions, the

former requiring a second plunger operation to complete the cycle. Push-button switches

should be used when a control or array of controls is needed for momentary contact

or for test functions or when used frequently. The push-button surface should be

concave or designed so as to prevent the fingers from slipping off the control.

Since there is no knob or lever position to indicate a maintained push-button's

actuation, lighted push-buttons are usually preferred. Non-illuminated push-buttons

may be used with an auxiliary pilot light but this decreases system reliability

and may cause the operator to search for the proper indicator light.

Rotary switches can be classified according to the type of sealing-closed or

open, with further sealing classifications in the sealed category. The most popular

sealing of a closed switch is explosion-proof, that is, the rated load can be switched

in an explosive atmosphere without causing the switch to explode. See Fig. 7A. This

enclosure is not watertight to immersion, but is sufficiently tight to prevent water

penetration in most applications. Often a rotary switch is made with a rubber "O"

ring between the shaft and bushing to prevent moisture from entering the switch

through the bushing. The advantage of a closed rotary switch, like that of other

switches, is the protection afforded by its enclosure. However, open rotary switches

offer an advantage, besides cost, that is very desirable in some applications. See

Fig. 7B. The accessibility of the switching contacts allows visual inspection of

their condition and even repair.

Rotary switches should be used when the circuitry involved requires more than

three positions. They should not be used when only two positions are needed. Momentary

actions are available in addition to maintained actions. Rotary switches can switch

current to as many as 24 loads or with as many as 12 poles or circuits per deck.

The number of poles can be increased by a factor of 3 or 4 by using several poles

per deck at the expense of the number of loads. The common contacts (poles) of each

circuit may be either shorting or non-shorting. A shorting contact activates the

next circuit during each switching cycle before removing power from the last circuit.

A non-shorting contact supplies power to only one circuit at a time.

Switches with concentric shafts are useful where a small package is essential.

Two switches are combined into a single unit with two distinct shafts. Combinations

of shorting and non-shorting contacts along with varied numbers of loads and poles

are available. However, complex designs of this nature reduce system reliability,

operator efficiency, and tend to degrade the over-all system effectiveness and should

be avoided if possible.

Round black knobs are frequently specified. Consideration must also be given

to the depth of the recess in the knob with the length of actuator shaft of the

switch and any possible interference with the mounting panel ( and face plate if

one is used) or the switch identification. Included in rotary switches are thumbwheel

switches. These are rather specialized in their application and are usually used

in conjunction with circuit boards. Most often the thumbwheel switch has ten position

with the output digital or binary coded.

Toggle switches are classified according to their number of poles, with each

group being further divided according to the sealing. Usually toggle switches have

one, two, or four poles; three -pole switches are available but do not enjoy the

same usage and popularity. The sealing is: 1. unsealed with varying amounts of enclosure;

2. toggle-sealed, that is, when submerged with water one-half inch above the bushing,

water will not enter the switch through the toggle seal; or 3. environmentally sealed,

that is when submerged completely and subjected to pressure equivalent to 56,000

feet altitude for several hours, depressurized, and allowed to remain under water

for several more hours, water will not be pumped into the switch. An environmentally

sealed toggle switch is shown in the photograph of Fig. 8A.

Toggle switches should be used in applications requiring two or three positions.

Generally, in a three-position toggle switch the center is the "off" position with

the extremes representing circuitry "on" conditions. These switches are also available

with "momentary-on" positions. Toggles with more than three positions should not

be used. When more than three positions are required, a rotary switch should be

specified.

A very popular safety feature, often selected as an alternative to a switch guard,

is the "pull-to-unlock" toggle lever, Fig. 8B. A spring-loaded cap or knob on top

of the lever requires the operator to lift it manually to allow movement to another

position. Guards are available ranging from complete enclosures of the toggle to

channel-shaped guards that require the operator to reach into the channel and actuate

the switch.

Slide and knife switches are the most basic, simple, and reliable of the manually

actuated switches. A slide switch is shown in Fig. 8C. Almost without exception

they are unsealed. They are usually enclosed or provided with some form of housing

to protect the operator. As with any switch, special functions, hybrids, and accessories

are available. The most popular slide and knife switches are used where economy

is a major consideration. Their application is limited to environments that do not

require sealing, except those knife switches used in outdoor fuse boxes which are

usually classified as rain-tight. Their function is similar to that of toggle switches.

Standard Switches

Almost any number of variations on the switches discussed here are available

- unusual or untested parts should be avoided. Such a selection most often contributes

little or nothing to the system effectiveness. A hard and fast rule which will enable

a designer to determine if a switch will function properly in his application usually

does not exist. The only criterion is the establishment of the application requirements

and then the selection of a suitable switch which will meet those requirements.

|

By Arthur F. Hackman

By Arthur F. Hackman