|

February 1960 Electronics World

Table of Contents

Table of Contents

Wax nostalgic about and learn from the history of early electronics. See articles

from

Electronics World, published May 1959

- December 1971. All copyrights hereby acknowledged.

|

All of the

oscilloscope measurement techniques presented in this 1960 Electronics World

magazine

article apply to 2018 circuit measurements. Anyone who attended a high school or

college electronics lab has created and measured capacitance, inductance and resonance

using an o-scope as part of a classroom exercise. We all were wowed the first time

we hooked up signal generators to both the horizontal and vertical deflection inputs

and observed rotating Lissajous patterns on the display. Don't tell me you didn't

twist the frequency and amplitude knobs of the sig gens with the delight of a kid

playing with an

Etch-A-Sketch. When I was taking labs in the 1970's and 1980's, school oscilloscopes

were all analog and had no handy-dandy digital readout marker functions that helped

make rise time and fall time measurements a little easier. We used the X- and Y-

trace position adjuster knobs to move the waveform to a convenient measurement point

behind the etched display grid, and then counted whole squares and interpolated

between them. The same applied to spectrum analyzers. There was undeniably a benefit

to learning the skill, but I definitely appreciate modern test equipment with digital

markers and math functions. All of the

oscilloscope measurement techniques presented in this 1960 Electronics World

magazine

article apply to 2018 circuit measurements. Anyone who attended a high school or

college electronics lab has created and measured capacitance, inductance and resonance

using an o-scope as part of a classroom exercise. We all were wowed the first time

we hooked up signal generators to both the horizontal and vertical deflection inputs

and observed rotating Lissajous patterns on the display. Don't tell me you didn't

twist the frequency and amplitude knobs of the sig gens with the delight of a kid

playing with an

Etch-A-Sketch. When I was taking labs in the 1970's and 1980's, school oscilloscopes

were all analog and had no handy-dandy digital readout marker functions that helped

make rise time and fall time measurements a little easier. We used the X- and Y-

trace position adjuster knobs to move the waveform to a convenient measurement point

behind the etched display grid, and then counted whole squares and interpolated

between them. The same applied to spectrum analyzers. There was undeniably a benefit

to learning the skill, but I definitely appreciate modern test equipment with digital

markers and math functions.

The Scope as a Resonance and LC Tester

By A. A. Mangieri By A. A. Mangieri

Test flybacks, check resonance, measure inductance or capacitance with two resistors

and your scope.

The modern oscilloscope is regarded by many as the most versatile of test instruments.

Few people claim to know all the uses to which it may be put. New uses are always

being suggested. The possibility of measuring resonance with the oscilloscope was

investigated because a convenient method of checking low-frequency tanks, in the

range of 1 to 200 kilocycles, was needed. Popular devices normally used to measure

resonant frequencies, like grid-dip meters, do not generally extend below 300 kc.

As for unknown values of an inductance or capacitance, they can be found by resonating

them against known components.

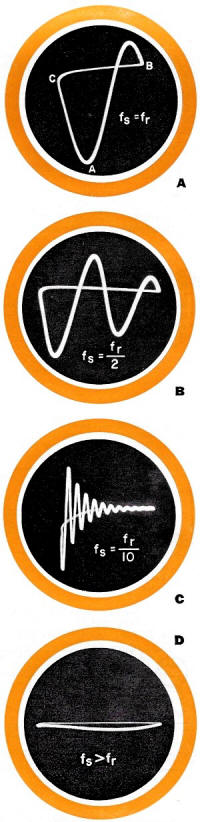

Fig. 1. Oscilloscope displays obtained (A) when sweep rate (fs)

and resonant. frequency of the tank (fr) are equal, (B, C) when fs

is a subharmonic of fr, and (D) when fs is greater than fr.

The method worked out was that of exciting a parallel connection of L and a with

the saw-tooth output from an oscilloscope. Circuit connections for the technique

are shown in Fig. 2. The saw-tooth voltage (E1) is applied to the

LC network and an output voltage (E2) is taken from the tank for application

to the vertical input of the oscilloscope. Isolation resistors R1 and

R2 are not critical: values anywhere from 50,000 to 250,000 ohms are

satisfactory.

Theory of Operation

A saw-tooth wave is an excellent source of a broad band of frequencies. In addition

to its fundamental, it contains a sequence of usable odd and even harmonics of progressively

smaller amplitude. The parallel LC circuit will exhibit a characteristically high

impedance at its single frequency of resonance.

We may understand behavior of the circuit if we first think of the saw-tooth

wave, E1 as a pulse that shock-excites the tank circuit. This results

in a damped, transient oscillation, E2. The frequency of oscillation

is determined by the LC tank and the damping by the "Q" of the circuit.

We will call the fundamental sweep frequency or repetition rate of the saw-tooth

waveform fs and the resonant frequency of the LC circuit fr.

If the sweep-frequency controls of the scope are adjusted so that these two are

equal (fs = fr), the oscilloscope pattern will resemble Fig. 1A,

displaying one cycle of oscillation. If the sweep frequency is one-half the resonant

LC frequency (fs = fr/2), a two-cycle display (Fig. 1B)

results, with the second cycle smaller in amplitude than the first. With fs

much lower than fr (fs = fr/10), the damped oscillation

of Fig. 1C results. If the sweep frequency should differ from the resonant

frequency in the other direction - that is, if fs should be greater than

fr, the waveform collapses as shown in Fig. 1D.

If fr is unknown, how can we determine when sweep frequency fs

is correctly set to it? This is done simply by adjusting the sweep frequency while

observing point A in Fig. 1A. This point will extend and retract vertically

as we sweep through the resonant frequency. The point of maximum extension (maximum

pattern height) occurs when fs = fr. Similarly, when we sweep

fs gradually through fr/2, point A exhibits like behavior,

but with reduced amplitude. During normal adjustment, point A will also seem to

move from side to side, and the retrace line (B-C) will move up and down. These

effects reflect the gradual shifting of phase between E1 and E2.

Calibration

To apply the technique, we must obviously calibrate the sweep frequency controls

of the oscilloscope. Where the fine-frequency control is not marked with a subdivided

scale, a dial plate with a hundred divisions may be fixed in place behind it. An

audio or other low-frequency oscillator may be used. Connect the oscillator output

to the vertical terminals of the oscilloscope and, for each frequency at which calibration

is made, adjust the scope controls to obtain a single-cycle display.

During calibration, keep the sync-amplitude control of the scope adjusted to

its lowest usable setting. This prevents excessive "pulling" of the sweep frequency

and permits the greatest possible accuracy. During actual resonance and LC tests.

the sync-amplitude control is set to zero. Despite the fact that the multivibrator

of the scope's sweep generator will be free-running with no sync, its stability

will be adequate in most cases. Nearly all oscilloscopes today, including some less

expensive ones, use some form of voltage regulation, insuring a reasonable amount

of frequency stability.

Arbitrary markings rather than actual frequencies should be marked on the scope

panel. Actual calibration frequencies should be plotted on graph paper. In this

way, a separate curve for each position of the coarse frequency control can be made

up, and all curves may be plotted on the same reference sheet. Semi-log graph paper

was found to be most practical.

Resonance Testing

To determine the resonant frequency of a parallel circuit, connect it to the

oscilloscope as shown in Fig. 2, and adjust sweep frequency to obtain a single-cycle

display while maximizing pattern height. Resonant frequency may then be read from

the calibration curve.

Conversely, to adjust an LC circuit to a particular frequency, set the scope

controls to that frequency and manipulate the value of either L or C to produce

the characteristic pattern. The direction in which the parallel combination is off

may be determined by comparing the shape of the initial pattern observed with those

in Fig. 1.

One practical application of the method has been in testing flyback transformers,

by measuring their self-resonant frequency. With the TV receiver de-energized, connect

the high end of the flyback transformer to the oscilloscope through the two isolation

resistors, as shown, and connect the low end of the transformer to the scope's ground

terminal. This self-resonant frequency will vary considerably from one type of set

to another, depending on design of the transformer itself and differences in circuit

loading. It will help to record the normal frequency for each type of circuit design

encountered for later comparison.

In testing the flyback circuit of a suspected receiver, moderate deviation from

the normal frequency may be expected due to manufacturing tolerances. However circuit

defects, such as open or shorted windings and cracked or loose cores, will result

in a marked change in inductance and therefore a large change in resonant frequency.

Is it also possible, as in other flyback testing techniques, to unload the transformer

gradually by disconnecting associated components one at a time to localize a defect.

Measuring Capacitance

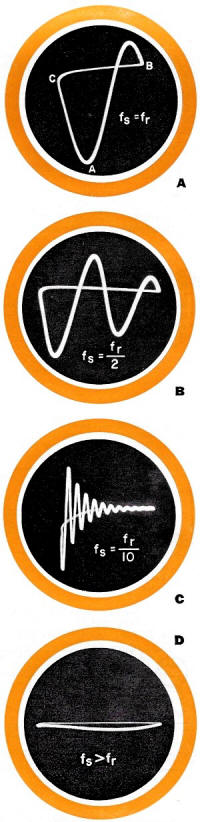

Fig. 2. Connections from circuit being measured to the scope

are very simple.

We can determine the value of an inductor or capacitor in a tank circuit if the

resonant frequency and the value of the other component in the LC combination are

known. Of the two methods available for measuring capacitance, the greater accuracy

and simplicity of one of them makes it the strongly preferred technique. In addition

to one (or more) inductor chosen as a standard reference, it relies on calibration

against several known capacitors. A capacitor decade box or a sequence of other

accurate capacitors will serve.

Using the arrangement of Fig. 2, each of the capacitors is connected in

turn across the reference inductor. The value of the latter need not be known exactly.

With each capacitor, the scope's fs is adjusted to equal fr.

A sheet of graph paper is then used to record the position of the sweep-frequency

controls for each known value of capacitance, and a curve may be plotted from these

individual readings. Calibration in terms of sweep frequency is not necessary.

To measure an unknown capacitor, connect it across the reference inductance in

the test circuit and adjust the sweep frequency for resonance. The value of C may

then be found by direct reference to the calibration curve. Neither the sweep frequency,

the exact value of the inductor, nor any other characteristics of the latter need

be taken into account once it has been chosen as the standard. Experimentation shows

that a choke of about 60 millihenrys can be used to measure capacitance from 100 μμf.

to 0.1 μf. High-"Q" inductors are preferred.

The alternative method of measuring C uses the curves already plotted for resonance

tests along with the known inductor already noted. In addition, the familiar formulas

involving reactance and resonance will have to be used for calculation of values.

Even here, the paperwork can be simplified by using a reactance slide rule. One

such inexpensive unit is made by Shure Brothers, Inc. Nevertheless, the technique

must take into account additional factors that will not be involved in the first

method described for measuring capacitance. For example, the reference inductor

will have a certain amount of distributed shunt capacitance across its terminals,

rendering it self-resonant at some frequency. This capacitance, Co, is

across any external capacitor that may be in parallel with the inductor.

If the inductance is known to start with, Co may be found by determining

the self-resonant frequency and using the formulas or the reactance slide rule.

To measure an unknown capacitor, connect it in parallel with the inductor in the

test circuit and find fr. From this frequency and the known value of

L, the value of C may be worked out or read on the reactance calculator. From the

value thus obtained, Co should be subtracted. Circuit "Q" also can be

a factor if an attempt is made to use an inductor over too wide a range of capacitance

values. If circuit "Q" is much less than ten, considerable error can result. For

a particular inductor, it is wise to limit the values of C that are used to measure

over a range that insures a circuit "Q" of ten or more. The latter factor may also

be calculated with the reactance slide rule.

Measuring Inductance

Capacitors of known value will obviously be needed to determine the inductance

of unknown coils, and such factors as "Q" and Co are also important.

However a simple method with few pitfalls does exist.

First find the self-resonant frequency, fo, of the unknown inductor.

Next, shunt sufficient known capacitance across this inductor so that fr

for the combination is about one-tenth of fo. Under these conditions,

Co will be small compared to C, so that the former will not cause significant

error. Also, circuit "Q" will generally be above ten. Using fr and the

added shunt capacitance as the known quantities, the inductance can be found using

the formula L = 1/4π2fr2C

or from the reactance calculator.

Summary

The measurement of low-frequency parallel-resonant circuits and of capacitance,

using the methods recommended here based on appropriate calculation curves, are

straightforward and reliable. Measurements involving more than one step and the

calculator (or formulas) will also be found useful to those who have no other suitable

equipment for making such checks.

Accuracies will obviously not approach those obtainable by producing nulls on

the bridges in laboratory-quality equipment. However, there is a question as to

how much accuracy is actually needed. Most measurements made by the methods described

here fell within five per-cent.

A final word of caution: some types of inductors with powdered-iron cores are

quite non-linear, inductance varying with applied voltage and frequency. These should

be avoided as reference inductors. No simple correction factors will compensate

for the errors they introduce. As to capacitors, paper and mica units show relatively

small changes in value even at higher frequencies and also have high "Q."

|