|

May 1969 Electronics World

Table of Contents

Table of Contents

Wax nostalgic about and learn from the history of early electronics. See articles

from

Electronics World, published May 1959

- December 1971. All copyrights hereby acknowledged.

|

Passive repeater

antennas have been used for a long time to overcome line-of-sight-limitations of

many - if not most - of the radio communications universe. Properly designed and

implemented passive repeaters can exhibit very high levels of efficiency, and in

some cases can actually provide gain by focusing signals impinging on a large panel

of multiple wavelength dimensions onto a smaller transmitter or receiver antenna.

That is known as aperture gain. Optical telescopes are a good analogy where for

the same level of magnification at a given wavelength, a larger aperture (refractive

lens or reflector mirror) results in a brighter image at your retina or CCD detector.

Interestingly, a passive repeater installation in Iran - a U.S. ally at the time

- is mentioned in this 1969 Electronics World article. Iran fell into radical

hands ten years later during the

Iranian

Revolution.

Radio Mirrors for Communications

By Ray D. Thrower /Field Services Manager, Microflect Co., Inc.

If you look carefully toward the right you can see a small elevated

house-like structure which is one of the active repeater stations of Columbia Basin

Microwave in Ephrata, Washington. This early winter photo gives an indication of

the difficulty in traveling to the station for maintenance. The building construction

is unique in order to permit access even when the snow reaches its peak winter depth.

Huge passive reflectors, which actually provide gain of 100 to 130 dB for u.h.f.

and microwave radio-relay stations, reduce installation and operating costs and

keep noise to a minimum.

Communications engineers are using large radio mirrors to redirect u.h.f. and

microwave radio signals over and around mountains and tall buildings which would

otherwise obstruct the radio beam. The use of the radio mirror, called a "passive

repeater" in the communications industry, eliminates the need for large numbers

of active radio-relay stations. The passive repeaters are replacing many active

repeaters (with their transmitters, receivers, and parabolic transmitting and receiving

dishes) and are reducing the cost of installing and operating high-density radio-relay

networks.

Microwave and u.h.f. radio beams behave quite a bit like light. They won't go

through buildings or mountains or any other path "obstruction." For radio system

design purposes, the solution to obstructed paths or for connecting points of communications

used to be the installation of an active radio-relay repeater. In some cases this

can be catastrophically expensive. With new advances in the techniques of reflector

technology, it is now possible to design microwave communications systems without

any active mountaintop repeaters whatsoever.

Advantages of Passive Repeaters

There are quite a number of economic and technical advantages cited by systems

engineers and operators who have gone to the passive-repeater philosophy of communications

system design. Active radio equipment requires continual maintenance. In the winter,

in some locations, active-equipment failures can mean a cold, dangerous night for

a maintenance man who must get to a mountaintop site to effect repairs. Special

snow vehicles, an extra-cost item, are necessary to get to most mountaintops during

the winter.

This passive repeater was installed high in the mountains of

Glacier National Park, in Montana, for a large microwave radio telephone system.

The passive repeater, once installed, requires little, if any, maintenance so

that technicians working on such a system never have to go to isolated mountaintop

sites in treacherous weather just to replace a blown fuse. This is an important

factor to safety-conscious operations managers.

Since the passive repeater requires no maintenance and no power, the cost of

building an access road and running a power line to a repeater location is eliminated.

The cost of access roads and power lines for an active repeater frequently exceeds

the installed cost of a passive repeater. The passive repeater is also considerably

less expensive than the active radio equipment.

Some typical operating and maintenance costs for an active repeater are on the

order of $1600 to $5000 per year depending on the complexity of the repeater station

and its accessibility. Access road construction costs are from about $1000 per mile

for simple graded roads across open country to $40,000 per mile, and more, in forested

mountains. One microwave system operator reported paying $240,000 for one and one-half

miles of access road.

Passive Repeaters in Use

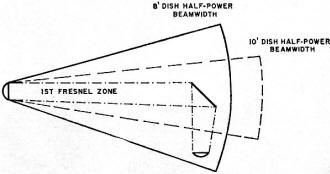

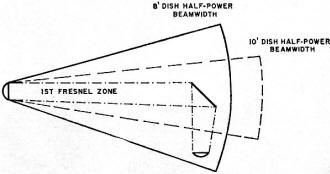

Fig. 1. Two methods of laying out a 600-voice channel, 6-GHz

microwave telephone system being installed in western Oregon. System at the left

uses active repeaters and seven sets of frequencies while system at the right uses

passive repeaters and four sets of frequencies. Note that three active repeaters

were eliminated at the right. Not only does this reduce the installation and maintenance

costs, but a system noise reduction of 3 dB can be realized. Curved lines below

are parabolic dishes of active repeaters; straight lines are passive reflectors.

The passive repeater communications system can provide service equivalent to

or better than that available from active repeater systems. Passive repeaters are

being used to relay voice, video, and data communications in a multitude of systems

around the world. The microwave backhaul systems from the new earth satellite stations

in the Philippines, Indonesia, and Brazil use passive repeaters. A telephone company

system in western U.S.A. has sixty-five passive repeaters. A 7-GHz system under

construction in Iran will have 15 passive repeaters. The microwave backhaul link

from the satellite earth station in Iran will also use a passive repeater. On the

Island of Oahu, Hawaii, there are no less than twelve passive repeaters in four

different systems.

The passive repeater is being used in greater numbers than ever before in communications

systems operated by oil pipelines, railroads, military and civil government agencies,

and common carriers. All types of modulation are used in these systems.

Active radio-relay repeaters contribute and amplify noise as well as the desired

signal. Since the passive repeater provides passive "gain," rather than electronically

amplified gain, it contributes no noise to the operating system. Active repeaters

also produce intermodulation products in the radio-relay baseband. These intermodulation

products are the result of the undesired mixing of different frequencies within

the receiver or transmission lines and result in a gradual degradation of the information

to be relayed. The radio mirror, being a passive device, contributes no intermodulation

products to the signal.

What About Gain?

One thing that surprises most people is the fact that a passive repeater has

gain. The question is always asked, "Gain, out of a flat surface? How can that be?"

Gain has to be defined. It is generally accepted to mean an increase in level over

a predetermined level. There are two types of gain available. One is by electronic

amplification; the other is by aperture amplification. For electronic amplification,

power must be applied or increased in order to get more gain. In aperture amplification,

the aperture must be increased to get more gain.

The passive repeater really gets its gain from the aperture it projects to the

incoming and outgoing radio beams. In antenna-system work (a passive repeater actually

forms an extended antenna system) gain is given in reference to an isotropic point

source; that is, a source that radiates equally in all directions. Any change from

an isotropic configuration will result in more energy being radiated in one direction

than in another. Therefore, there will be gain in one direction, referred to the

isotropic source. The passive repeater, with its large aperture, will result in

considerable gain over an isotropic point source. For example, a 40-foot by 60-foot

passive repeater, with a horizontal included angle of 90° for the radio beam

will have a gain of 128.5 dB at 11 gigahertz. (A somewhat smaller reflector, shown

on our cover, will provide a gain of about 110 dB in the 6-GHz band and 120-dB gain

in the 11-GHz band. - Editor)

Fig. 2. Single reflectors are used for turn angles of up

to 135°, as shown at the center. For greater angles, double reflectors, as shown

at left and right, are used. Spacing between the two reflectors is not extremely

critical. Depending on operating frequency and reflector size, the spacing may be

from under 100 feet to over a mile or more without degrading the over-all system

performance by more than a dB or so.

Quite probably the difficulty many people have in understanding how the passive

repeater, a flat surface, can have gain relates back to the common misconception

about parabolic antennas. It is commonly believed that it is the focusing characteristics

of the parabolic antenna that gives it its gain. Therefore, goes the faulty conclusion,

how can the passive repeater have gain? The truth is, it isn't focusing that gives

a parabola its gain; it is its larger projected aperture. The focusing is a convenient

means of transition from a large aperture (the dish) to a small aperture (the feed

device). And since it is projected aperture that provides gain, rather than focusing,

the passive repeater with its larger aperture will provide high gain that can be

calculated and measured reliably. A check of the method of determining antenna gain

in any antenna engineering handbook will show that focusing does not enter into

the basic gain calculation.

Projected aperture is the effective "window" of energy seen by the antenna at

the active terminal as it views the passive repeater. The passive repeater also

sees the antenna as a "window" of energy. If the two are far enough away from one

another, they will appear to each other as essentially point sources.

Curing Fading

Passive repeaters have been installed to cure fading of microwave signals due

to unwanted ground reflections (multipath propagation) or ducting conditions. Installation

of the passive repeater provides several advantages in a fading path. First, it

offers angular discrimination to unwanted signals that might occur where the path

goes over highly reflective terrain, such as flat land or water or even cloud or

fog layers. Since the angle of reflection is equal to the angle of incidence, any

unwanted signals being received from an angle other than the desired angle will

be redirected off path and the magnitude of potential interference will be reduced.

When there is ducting-type fading, the installation of a passive repeater can

change the angle at which the microwave beam travels through the duct layer so that

it is not so subject to being ducted off path. The sharper the angle at which the

beam cuts through a duct layer, the less opportunity there is for the beam to be

ducted away from the path.

Installation of the passive repeater actually can change the path geometry to

such a degree that the problems causing the fading may be done away with entirely.

Engineers who design communications systems with passive repeaters have a different

engineering philosophy than the engineers who put active repeaters on mountaintops.

Quite a number of systems have been reconfigured to eliminate mountaintop active

equipment, as shown in Fig. 1. Originally, this system, installed in western

Oregon, was to have three active repeaters to connect the various communities. However,

the engineers working on the system design decided to use a number of passive repeaters

instead. By so doing they were able to do away with the need for three active repeaters

in the 600-voice-channel common-carrier microwave system. The system has been partially

completed and is operating according to design specifications.

Double passive repeaters are used when the turn angle for the

microwave beam exceeds about 135 degrees. Each of these reflectors is 30 by 32 ft

in size. One reflector receives energy from a 6-GHz telephone company radio terminal

some 25 miles away and the other redirects as many as 600 simultaneous phone conversations

to a receiving station about 6 1/2 miles away.

Fig. 3. The passive reflector need not reflect all the energy

between the half-power points but merely the energy in the first Fresnel zone. The

half-power points may be a mile or more apart after a distance of 30 miles while

the radius of the first Fresnel zone at 30 miles with the energy being redirected

for another 4 miles is only about 55 ft at 6 GHz. A reflector larger than this would

reflect energy in the second Fresnel zone, which would be out-of-phase and cause

destructive interference. By redirecting even a portion of the energy in the first

Fresnel zone, it is possible to obtain practical gains of 100 to 130 dB. Plane reflectors

are more efficient and less expensive than back-to-back parabolas.

Another advantage derived is that frequency congestion in a given area is reduced

by using a passive repeater. The all-active arrangement at the left in Fig. 1

would have required seven sets of frequencies where the passive-repeater system

at the right will require only four sets of frequencies. This is a critical consideration

where an area is approaching saturation of the frequency spectrum.

Single passive repeaters are used where the angle to be turned, the horizontal

included angle, is 135° or less. When larger angles are to be turned, the effective

aperture of a single passive repeater would be small and inefficient so double passive

repeaters are used to achieve high aperture efficiency (Fig. 2).

Another area of difficulty in understanding the passive repeater is the matter

of beam spreading. Many engineers and technicians believe the passive repeater must

intercept all or most of the microwave beam between the half-power points (the -3

dB arc). After traversing a distance of 30 miles or so the half-power points of

a 5-GHz microwave beam may be spread to almost one mile apart. The small antenna

at an active repeater cannot even begin to intercept all the incident energy from

a distant transmitter.

In the case of the passive repeater, it is the Fresnel zone radius energy that

is intercepted and redirected. For a 6.0-GHz signal traveling over a sixty-mile

path, the radius of the full first Fresnel zone at midpath (30 miles) is only 112

feet. And since it is seldom necessary to intercept even all of this energy, the

construction of practical-size passive repeaters is relatively easy (Fig. 3).

It is necessary to keep the face of the passive repeater flat at microwave frequencies.

This is mandatory since any distortions of the reflector face will degrade the signal.

The face of the passive repeater must be flat to a tolerance of -1/8th wave length

over the full face of the reflector. Notice that there is not a "+" tolerance factor.

If there are any deviations from the flat reference point they must be concave rather

than convex as a convexity would result in beam dispersal.

The communications engineer will design his system on the basis of calculating

each path rather than immediately ruling out passive repeaters on the basis of archaic

"rules of thumb." No rule of thumb can possibly take in all the variables including:

transmitter power, parabolic antenna size, path lengths, receiver threshold levels,

and operating frequency. Another variable that must be considered is that of channel

loading. How many voice or data channels will be carried on the radio? Or will there

be video information? Recognizing the variables involved, the knowledgeable engineer

will compute his paths to determine if a passive repeater will work or if, indeed,

an active repeater is needed.

Radio mirrors are installed not only on snow-bound mountaintops

but also in the tropics. This 30 by 40-ft repeater is installed on the island of

Oahu and redirects a microwave signal capable of carrying 960 simultaneous voice

conversations between Wahiawa and Honolulu, Oahu, Hawaii, a distance of over 23

miles. At a frequency of 6 GHz there cannot be any distortion greater than 0.164

inch over the full face of the radio mirror shown.

The knowledgeable engineer or technician will also consider the economics of

his active repeaters when they are necessary. Would it be less expensive to put

the active repeater down by an existing access road (perhaps county or state maintained)

and near existing power and then use a couple of passive repeaters on a nearby hilltop

to provide the needed path clearance?

Companies that specialize in the manufacture and design of passive repeaters

frequently have both literature and seminar training sessions for interested groups

at nominal fees. Usually, a letter request is all that is required to obtain technical

data.

References

Chipp, R. D. & Cosgrove, T.: "Economic Analysis of Communications Systems".

Seventh National Communications Symposium, Utica, N.Y. 1961.

Jakes, W. C., Jr. & Robertson, S. D.: "Antenna Engineering Handbook". Edited

by Henry Jasik. McGraw-Hill Book Company, Inc., First edition.

Norton, M. L.: "Microwave System Engineering Using Large Passive Reflectors",

IRE Transactions on Communications Systems, September, 1962.

Thrower, Ray D.: "Passive Repeater Installations Can Reduce Microwave System

Costs", Communications News, October, 1967.

"Passive Repeater Engineering Manual Number 161", Microflect Co., Inc., Salem,

Oregon. 1961.

"Microwave Path Engineering Considerations - 6000-ENG", Lenkurt Electric Co.,

Inc., San Carlos, Calif. September, 1961.

|