|

May 1961 Electronics World

Table of Contents

Table of Contents

Wax nostalgic about and learn from the history of early electronics. See articles

from

Electronics World, published May 1959

- December 1971. All copyrights hereby acknowledged.

|

My first experience with negative

resistance was when an engineer I worked for at Westinghouse Electric, in Annapolis,

Maryland, used a tunnel diode to design a simple oscillator circuit. The project

we were working on required an absolute minimum number of parts, with everything

implemented using bare die on a custom polyimide substrate printed circuit board.

I did the assembly, wire bonding, and encapsulation, and often initial test. In

this 1961 Electronics World magazine article, Mr.

Rufus Turner does a nice job of briefly covering the history and application of

negative resistance devices; tunnel diodes were not the first of the kind.

See author's "A.C. Negative-Resistance Devices" article in the July 1963

Electronics World.

Negative Resistance - What It Is & How It's Used

Fig. 1 - Illustration of basic negative resistance principle.

By Rufus P. Turner

Negative-resistance devices have been with us long before the tunnel diode. Here

are descriptions of some of them, along with how and why they operate.

The tunnel diode has turned many minds toward negative resistance for the first

time. Negative resistance is not new, but some electronics people just a few years

ago had not heard of the phenomenon, or had forgotten what they once learned about

it, because they would give a pitched battle on the subject. Always, they challenged,

"How can you make any resistance lower than zero?", which only shows that they thought

in terms of wiping out resistance, not of changing its sign. Zero resistance is

one thing; while negative resistance is something else again.

Fig. 2 - Negative-resistance E-I curves.

The concept is easily demonstrated to the dubious, in the following common-sense

terms. Consider a negative resistance (Rn) connected in series with a

conventional (positive) resistance (R) and an adjustable d.c. source (E), as shown

in Fig. 1. The following facts are evident: (1) the same current, I, flows

through all parts of this series circuit and is determined by the voltage E and

the sum of the two resistances (without regard to the negativity of (Rn),

so Ohm's Law is not violated. The interesting point is what happens to the voltage

drops, e and en, produced by this current: whereas e increases with E

and I in the normal manner, en decreases. (Increase I, and en

decreases; decrease I, and en increases.) Thus, the EI curve of this

component must have a negative slope. (2) Irrespective of their magnitudes, however,

e + en =E. So Kirchhoff's Second Law is not violated. (3) Whereas the

conventional resistance consumes power, the negative resistance seems to deliver

power. Actually, the total power supplied by the d.c. source remains the same; it

is only distributed differently between the positive and negative resistances. Thus,

the Law of Conservation of Energy is not violated.

Most negative-resistance devices have a current or voltage region in which their

resistance becomes negative. Outside of this region, the resistance may be positive.

In Fig. 2A, for example, as current through the device is increased, the voltage

drop across the device increases from 0 to A, indicating positive resistance, but

then decreases from A to B as the current is further increased, indicating negative

resistance. In Fig. 2B, there is a negative-resistance region (AB) between

two positive-resistance regions (OA and BC). Thus, at voltage Ex device

current may have anyone three values (I1, I2, or I3).

Another type of negative-resistance device would have the current and voltage axes

swapped. Positive-resistance regions are negative-resistance regions unstable.

Fig. 3 - Equivalent circuits of negative-resistance devices.

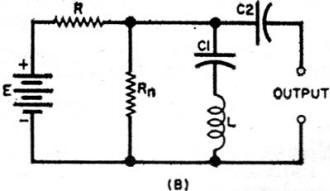

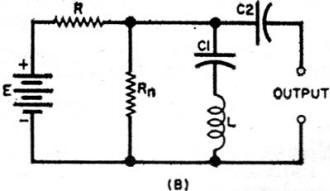

Circuits simulated are (A) relaxation oscillator, (B) sinusoidal oscillator, (C)

amplifier, (D) flip-flop.

Fig. 4 - The arc-converter transmitter.

Fig. 5 - The early split-anode magnetron.

Fig. 6 - Circuit and curve for the dynatron.

Fig. 7 - Grounded-grid amplifier application.

Fig. 8 - Point-contact transistor operation.

Fig. 9 - The junction-transistor duo circuit.

Fig. 10 - Uni-junction transistor circuit.

Fig. 11 - Point-contact germanium diode circuit.

Fig. 12 - Circuit showing use of thermistor.

Negative resistance may be put to work for various tasks, such as oscillation,

amplification, frequency conversion, harmonic generation, counting, and switching.

The circuits usually are very simple, since the negative resistor generally is a

2-terminal device. Fig. 3 shows several typical circuits. A rule of thumb is

that when a negative resistance (Rn) is operated from a d.c. supply in

series with a positive resistance (R), shunting Rn with a capacitor (as

in Fig. 3A) produces a relaxation oscillator, and shunting it with an LC tuned

circuit (Fig. 3B) produces a sinusoidal oscillator. Fig. 3C shows one

of many negative-resistance amplifier circuits. Here, the d.c. voltage, Ed.c.,

biases the negative resistor, Rn, into its negative-resistance region,

the a.c. signal is supplied by a generator having internal resistance Rg,

and the output signal is developed across the load resistance, RL If

Rn were not in the circuit, EL would equal EgRL

(Rg + RL). With Rn present, however, operation

is somewhat different. In this case, the gain increases so that the amplifier may

go into oscillation. Here the negative resistance is simulated by the use of positive

or regenerative feedback.

Flip-flop action may be obtained when a negative resistor is operated so as to

provide three-point response, such as shown in Fig. 2B. The device is initially

biased at its lowest EI point (I1 the first stable state in Fig. 2B).

If the voltage then is raised momentarily higher than the value Ex, the

device conduction will flip to the second stable state (I3 in Fig. 2B),

where it will remain until switched back to I1 or until the bias is momentarily

interrupted. Fig. 3D shows a two-legged circuit (with two negative resistors,

Rn1 and Rn2) employing this principle. First, Rn1

in one leg conducts at the low point (I1 in Fig. 2B) and Rn2

in the other leg is at point I3 in Fig. 2B. Momentary increase of

the bias by application of the trigger pulse shifts Rn1 to point I3.

But because of the voltage drop across the common series resistor, R1

both legs cannot be maintained "on" i.e., at conduction point I3) simultaneously.

So Rn2 switches "off" (i.e., to point I1. Thus, alternate

trigger pulses switch the output back and forth between Output 1 and Output 2.

Negative-Resistance Devices

The tunnel diode is a simple, convenient, and practical negative-resistance device

but it is not the first component to provide -R. The answer to the question, "When

were you ever able to buy a negative resistor?" is "For a long time, indeed, but

it was called by other names; negative resistance was not its main function." Devices

which exhibit negative resistance have come forward from the early days of wireless

to the present time, and it seems likely that new ones will be discovered long after

the tunnel diode has become commonplace. The following discussion describes a few

of the most prominent devices other than the tunnel diode. Only d.c.-operated devices

are included.

Arc. In 1900, Dudell discovered oscillation in the d.c. electric arc, and Poulsen

soon put this device to work as a generator of continuous waves which finally actualized

early radiotelephony. (The arc must not be confused with the spark transmitter,

which generates damped waves.)

Fig. 4 shows the basic circuit of an arc transmitter. To increase efficiency,

the arc was operated in a hydrocarbon atmosphere; and, for good heat conduction,

one electrode was made of copper. The applied voltage was from 200 volts to several

kilovolts d.c. and power ratings extended up to 1000 kilowatts. In the 1920's, many

of the high-powered government radio stations were arc-equipped. Long wavelengths

were used. The arc gave way to the more efficient and compact, clean-operating vacuum

tube but it is important historically as an early, high-powered, negative-resistance

device.

Magnetron. The magnetron (first reported in 1921) is a vacuum diode tube in which

negative resistance can be obtained through the action of electrons in a strong

field produced parallel to the tube electrodes by an external permanent magnet.

Fig. 5 shows one type of magnetron. Here, the anode (plate) of the tube is

split into two halves. Electrons tend to pass from the filament or cathode to both

halves of the anode; but actually pass in the greater number (producing high current)

to the half which is at the lower potential. This effect of increasing anode current

by lowering anode voltage corresponds to negative resistance. This type of magnetron

is used up to 1000 mc.; other types at higher microwave frequencies.

Dynatron. Another old-timer (1918) is the dynatron effect in tetrode vacuum tubes.

Fig. 6A shows a typical dynatron oscillator circuit. In this arrangement, the

tube screen is operated at a higher positive voltage than the plate. Secondary emission

from the plate is responsible for the negative-resistance effect. (As the plate

voltage is increased, the velocity at which primary electrons strike the plate and

the number of secondary electrons that accordingly are emitted increase. The secondary

electrons are attracted back to the more positive screen, thereby reducing the plate

current and resulting in the negative slope from A to B in Fig. 6B.)

Grounded-Grid Amplifier. Under certain conditions, a grounded-grid amplifier

provides negative resistance. One such condition occurs in the telephone repeater

amplifier, shown in simplified form in Fig. 7. This amplifier delivers power

to the telephone circuit in which it "rides," instead of absorbing power, hence

qualifies as a negative resistance. Voice currents from the transmitter (microphone)

produce instantaneous currents represented by the dotted arrows, B and D. These

currents, in turn, cause a plate current, represented by the solid arrow C, which

is opposite to D because of 180° phase shift by the tube. This plate current

induces a voltage across the line winding of the transformer, represented by solid

arrow A, which is in series-aiding to the transmitter voltage. This induced voltage,

being in-phase with the speech voltage, aids the latter, causing more current and

power in the receiver. (One of the actions of a negative resistance is, as we have

shown earlier in this article, the delivering of power to the circuit.) When the

amplifier is not operating, the voltage drop across the transformer absorbs power

(positive-resistance action).

Point-Contact Transistor. If positive feedback is introduced in a device which

has a higher-than-1 current gain, the input resistance of the device will be negative

over a portion of the conduction characteristic. The point-contact transistor is

such a device. In Fig. 8A, positive feedback is provided by the external base

resistor, Rb. As the d.c. input (emitter) current is increased, as shown

in Fig. 8B, the emitter voltage (Ve) increases positively to A

and then to B, then negatively from B to C, and positively again from C to D. The

central negative-resistance region (BC), bounded on each side by a positive-resistance

region (AB and CD), gives the type of curve shown earlier in Fig. 2B, which

is valued for flip-flop applications. Viewed from emitter to ground, a point-contact

transistor operated in this manner is a negative resistance.

Direct-Coupled Junction Transistor Duo. The junction transistor has a current

gain of less than 1 when connected regeneratively (common-base circuit), so it cannot

be used directly as a negative resistance in the way that the point-contact transistor

can. However, two junction transistors may be connected in a manner such that a

negative resistance is "seen" at the input terminals of the circuit. In Fig. 9A,

the common emitter resistor, Re is analogous to the common cathode resistor

in a cathode-

coupled tube circuit. Positive feedback voltage is developed across this resistor

by the second transistor, V2. The plot of V1 base voltage

(Vb) vs base current (Ib) has the shape shown in Fig. 9B,

a negative-resistance region appearing between B and C. Viewed from the V1

base to ground, the circuit is a negative resistance when Re has the

proper value to place the operating point of V1 along the negative slope

(BC in Fig. 9B).

Uni-junction Transistor. This device, also called a double-based diode, consists

of a bar of n-type silicon with an ohmic (non-rectifying) base contact at each end

and a single p-n junction near the top end. Fig. 10A shows a uni-junction circuit.

The junction is biased by the input voltage in such a way that its lower half is

positive with respect to base 1 and acts as an emitter, whereas its upper half is

negative with respect to base 2 and acts as a collector. This simultaneous emitter

and collector action produces a negative-resistance characteristic (region CD in

Fig. 10B).

Point-Contact Germanium Diode. The point-contact germanium diode exhibits negative

resistance when biased highly in the reverse direction. Fig. 11A shows the

circuit. As the reverse current is increased from zero (Fig. 11B), the diode

voltage drop increases to A, showing positive resistance. As the current is increased

further, the diode voltage drop then decreases from A to B, revealing negative resistance

which is available at terminals X-X. Unfortunately, the diode is overloaded when

in the negative-resistance condition and is soon damaged by overheating. This has

prevented exploitation of the effect, although the point-contact diode operated

in this manner will oscillate, amplify, and provide bi-stable switching action.

Thermistor. The thermistor, a temperature-sensitive resistor, exhibits negative

resistance over a portion of its EI characteristic, which seems to be dependent

upon internal heating to some extent. The thermistor is not a rectifying device,

therefore it has no polarity; current may be passed through it in either direction.

Fig. 12A shows a thermistor circuit. Fig. 12B shows the response: as the

voltage (E) is increased, the thermistor current (I) increases from zero to point

A, a peak dependent upon internal and ambient temperatures and upon the composition

of the thermistor material. As the voltage is increased further, the current decreases,

as from A to B, revealing negative resistance. The latter is available for use at

terminals X-X.

Because negative resistance in the thermistor depends upon heat effects and since

there can be appreciable thermal inertia in the device, use of the thermistor in

negative-resistance oscillators, amplifiers, and switching circuits is limited to

very low frequencies.

Additional Devices

The devices chosen for review in this article are d.c.-operated, and they qualify

as resistances. In addition to these, there are certain a.c.-operated devices which

can be made to display a negative slope in their conduction characteristics. It

would seem proper, however, to term these negative-impedance devices. In some applications,

these devices are less flexible than their d.c. counterparts because they require

a.c. power supply (either a.f. or r.f.).

Such devices include ferro-resonant elements (ferristors), ferro-electric capacitors,

voltage-sensitive capacitors (silicon capacitors or varactors, and ceramic voltage-sensitive

capacitors), and the several types of magnetic amplifier devices and saturable reactors.

Posted June 27, 2024

(updated from original post

on 6/16/2016)

|