|

September 1967 Electronics World

Table

of Contents Table

of Contents

Wax nostalgic about and learn from the history of early electronics. See articles

from

Electronics World, published May 1959

- December 1971. All copyrights hereby acknowledged.

|

This 1967 Electronics

World magazine article highlights a potential revolution in microwave technology

through new semiconductor devices that could miniaturize and drastically reduce

the cost of microwave sources. The focus is on two promising devices: the Read p-n

junction diode and the Gunn bulk gallium arsenide oscillator. The Gunn device, discovered

accidentally by Dr. J.B. Gunn at IBM, operates on a radical principle - a bulk

semiconductor material oscillates at microwave frequencies without external tuned

circuitry when a threshold voltage is applied. Key to the Gunn effect is the unique

property of gallium arsenide, which features a second conduction band. Electrons

entering this high-energy, low-mobility band create "domains" that drift slowly

from cathode to anode, causing current oscillations. This generates microwave frequencies

based on the domain's transit time across the material. Though simpler and cheaper

than existing devices, the Gunn oscillator faced challenges in power output and

reliability. The article concludes that while it was uncertain which device would

dominate, the Gunn effect represented a significant breakthrough poised to enable

new consumer microwave applications. Note the "waterfall" chart in Figure 3,

which was not referred to as such because the term did not appear until the 1990s

when finance and management firms coined the name.

Gunn Oscillators

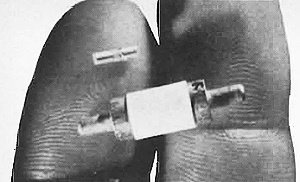

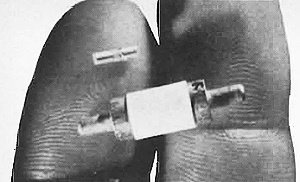

The larger device is intended for the Gunn bulk oscillator, while

the smaller device houses a Read-type junction diode

By David L .Heiserman

A new type of microwave semiconductor that may one day replace present complex

and expensive sources, and create new consumer microwave communications and radar

devices.

There is little doubt in the minds of semiconductor scientists and engineers

that microwave technology is on the threshold of a miniaturization and cost revolution.

A new breed of simple microwave semiconductors may one day replace our present complex

and expensive microwave sources and create a whole new line of consumer microwave

communications and radar devices.

The makers of the revolution will be the new transit-time semiconductors best

represented by the Read p-n junction diode and the Gunn bulk gallium arsenide oscillator.

( See "New Frontiers in Semiconductors" on page 78 of the March, 1967 issue.) At

this stage of development, however, no one can say which device will eventually

set the micro-wave revolution into motion - both have advantages and disadvantages,

and both are plagued by production reliability problems.

The theories of operation of both devices are rather new. The Read-type device

operates on the well -known principles of the zener and tunnel diodes with the new

idea of semiconductor electron transit time tying the two effects together. The

operation of the Gunn device, however, represents a radical departure from conventional

semiconductor thinking. In this respect, the Gunn device is worthy of closer study.

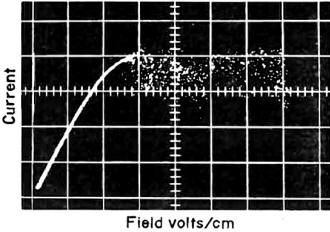

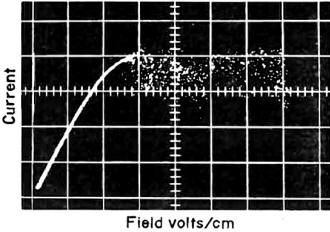

Fig. 1 - The current through bulk GaAs increases with an increasing

amount of applied d.c. voltage until the conduction band electrons gain enough energy

to skip upward into high energy, low-mobility band. At this threshold voltage (about

3000 volts /cm or about 6 volts of applied voltage) the GaAs sample will oscillate

without any external tuned circuitry.

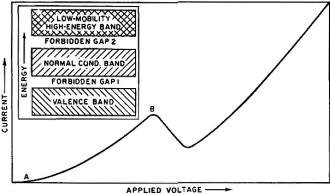

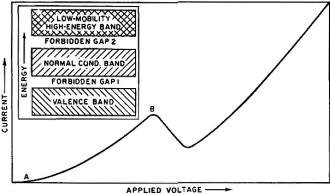

Fig. 2 - The quantum- energy diagram (shown in the inset) along

with a corresponding current-voltage curve for bulk gallium arsenide are illustrated

below. The existence of the second forbidden gap and the low- mobility, high- energy

conduction band gives GaAs quite different properties from the usual semiconductor,

such as n -doped silicon, showing no negative R.

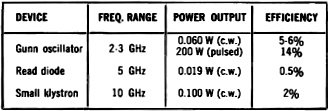

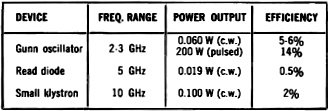

Table 1 - Performance of Gunn and other microwave devices.

Gunn's Discovery

Those of us who have been working in electronics for more than a few years associate

semiconductor devices with one or more p-n junctions. We think in terms of holes

and electrons, minority and majority carriers, junction potentials - always in terms

of at least one pair of p and n semiconductor materials within one device. To think

of an operational semiconductor made up of only one type of semiconducting material

(a bulk semiconductor) is, traditionally, to think of an impossibility. Despite

conventional thinking, the "impossible" was accidentally discovered by Dr. J.B.

Gunn at IBM's Watson Research Center.

In 1963, Gunn was running a series of routine experiments on a 0.005-inch thick

slice of homogeneous n -type gallium arsenide when he noticed some unexpected coherent

r.f. oscillations on his oscilloscope. Checking the setup for possible stray reactance

or faulty components, he discovered that the plain n-doped material was oscillating

at slightly less than 1 GHz (1000 MHz) with nothing more than a 6-volt d.c. power

supply connected to the terminals (Fig. 1). What had been a purely theoretical possibility

became a fact - Gunn found a semiconductor material that could oscillate in the

microwave region without benefit of external tuned circuitry.

Gunn and his associates soon realized that they had uncovered a phenomenon that

could not be explained in terms of the usual semiconductor theories, so they were

forced to try new theories and experimental techniques. The theoretical model of

the oscillator, as finally developed, represents one of the biggest sidesteps from

the mainstream of semiconductor thinking since the introduction of the laser diode.

Negative Resistance in Bulk GaAs

Without the benefit of the usual p-n junction, the Gunn oscillator demonstrates

negative resistance properties. The quantum energy diagram and corresponding I-V

curve are shown in Fig. 2. The diagram shows the usual forbidden gap between the

valence and normal conduction bands. These regions in GaAs have the characteristics

of any other n-type semiconductor such arsenic-doped silicon. The GaAs, however,

has an additional forbidden gap and a special conduction band that differs from

the first in two important respects. First, carriers (electrons in the case of GaAs)

can cross the second forbidden gap only when the applied d.c. potential reaches

an extraordinarily high value of 3000 volts per centimeter. Second, carriers that

do gain enough energy to skip into the second conduction band effectively gain some

mass and thus travel much more slowly through the semiconductor than their lower

energy counterparts in the first conduction band.

The second conduction band is thus described as one containing only high-energy

carriers which travel with un- usual slowness through the semiconductor. It is this

additional conduction band that makes it possible for an n -type bulk semiconductor

to show negative resistance.

Referring to the I-V curve in Fig. 2, the nonlinear slope between points A and

B is due to the increasing fraction of valence electrons skipping upward into the

high-mobility first (normal) conduction band under the influence of a small applied

voltage.

As the applied e.m.f. is increased beyond point B, however, the current drops

off sharply. It is at this point that some of the electrons in the low-energy, high

-mobility first conduction band enter the high-energy, low-mobility second conduction

band. If electrons move slower in the second conduction band than they can in the

first, it follows that increasing the percentage of electrons in the second conduction

band will cause a corresponding decrease in the net rate of electron flow through

the material. As the applied voltage passes beyond point B, then, the current through

the GaAs sample decreases. This, of course, is the general description of a negative-

resistance effect.

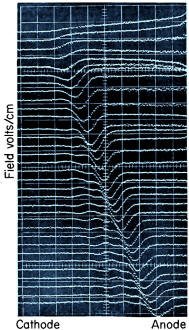

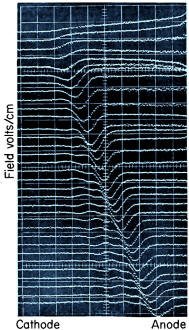

Fig. 3 - The low-mobility, high-energy electron domain passing

through the Gunn device. The domain builds up near the cathode and moves with relative

slowness to the anode, holding the current through the semiconductor to a minimum.

Although the ordinate of the oscillogram is in terms of field strength, the downward

progression of traces has no physical meaning except to display the chronology of

the shock wave that is produced.

The negative-resistance, junction-type semiconductors in use today require some

capacitance or inductance to sustain oscillation while the Gunn device does not.

So, negative resistance in bulk semiconductor theories are potentially useful, but

cannot wholly account for the Gunn effect.

Electron Domain Transit Time

Electron Domain Transit Time The theory that finally rounded out the explanation

of the Gunn effect involves the new concept of slow-moving, high-energy packets

or "domains" within a bulk semiconductor.

If a sufficient voltage (the threshold voltage) is applied to a thin slice of

n-type GaAs, electrons skipping into the second conduction band tend to collect

into discrete energy domains. Further, if the GaAs is of sufficient purity and the

applied voltage is carefully regulated, one and only one domain can exist within

the material at any one instant.

Since this one domain is made up of second conduction band electrons, the domain

will behave exactly as the electrons described in connection with Fig. 2. The domain

will drift with relative slowness from cathode to anode, holding the net current

flow through the semiconductor to a minimum.

Once the domain reaches the anode, it disappears momentarily and current surges

through the material via the first conduction band. This surge continues until another

high-energy, low-mobility domain forms at the cathode. The current through the bulk

semiconductor, then, is low during the electron domain transit time and relatively

high during the brief period of time it takes to form another domain at the cathode.

Thus, the Gunn device demonstrates current oscillations, the period of which depends

on the rate of domain travel and the physical length of the bulk semiconductor material.

The oscillogram of Fig. 3 shows the high-energy domain passing through discrete

points along the length of a thin slice of bulk GaAs. The trace at the top shows

the domain leaving the cathode. In the following traces, the moving electron domain

is shown at points progressively closer to the anode. If the frequency of oscillation

is assumed to be about 1 GHz, the traces cover an interval of about 1 μs.

At the present stage of semiconductor technology, the Gunn device's advantages

of small size, low cost, and simplicity must be weighed against the disadvantages

of lower operating frequency and low c.w. output power. Placed beside the Read-type

devices, the Gunn oscillator has about a 50 percent chance of becoming the microwave

source of the future. See Table 1.

Regardless of the final outcome, the Gunn effect described in this article represents

another opening to products and industrial equipment thought impossible a few years

ago.

|