|

December 1959 Electronics World

Table of Contents

Table of Contents

Wax nostalgic about and learn from the history of early electronics. See articles

from

Electronics World, published May 1959

- December 1971. All copyrights hereby acknowledged.

|

My long-established collection

of soldering aid and tuning wand tools still gets a fairly regular workout - but

not necessarily for soldering tasks. Because of their purpose-designed ends, they

come in handy for all sorts of model building activities. Most are non-metallic,

meant for bending and poking, and are very strong and heat resistant. The metal

types are still required for direct contact with molten solder. One of the best

tips offered in this 1959 Electronics World magazine article is for when replacing

a leaded component on a printed circuit board (PCB). If possible, rather than heating

the landing pad and plated through-via to remove the leads, just clip the leads

far enough from the PCB surface to create a post or loop to solder the new component

to. Doing so creates a mechanically sound solder joint without undue risk of damage

to the PCB metal or laminations. Interestingly, the PCB in this article contains

a vacuum tube plug-in socket.

Fix Those Printed-Board Defects

By Chester S. Lawrence By Chester S. Lawrence

Practical experience plus recommendations of the manufacturer equal solutions

for thorny problems.

There is virtually no type of electronic equipment now in widespread use in

which printed boards have not appeared. Yet, still regarding these devices with

suspicion, we often find ourselves saying, "Who wants them?" Well, let's face the

facts: the boards are less costly to use and take up less room; so we'll be running

into them more and more.

The great difficulties encountered in printed-circuit repair fall away once you

know how to go about the matter. We found this to be so as the result of considerable,

recent experience with a large number of sets using printed wiring. As it happens,

this experience was predominantly with the sets of one manufacturer, RCA, but the

problems and their solutions are generally applicable to other sets. Perhaps the

best way of presenting the relevant experiences is in the form of individual case

histories, just the way they happened, with the mistakes as well as the successes,

since both types of experience have value.

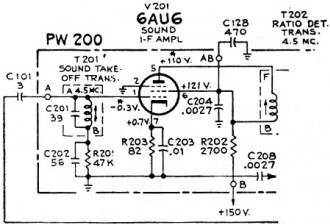

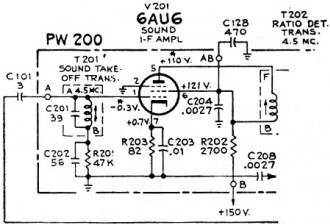

Fig. 1 - Poor contact produced intermittent audio output

in this RCA circuit.

Fig. 2 - One of the terminals of T201 had broken

away from the printed board.

We were called on the first set just as the World Series was beginning. The complaint

on this RCA was vanishing sound. When we arrived, the customer was steaming. The

set - and the ball game - were on, but the sound was off. After persuading the customer

to let us take a look to see what could be done, we got to work.

Off came the back and on went the cheater cord. When the set went on, we pulled

out a 6AQ5, the audio-output tube. This produced a very normal thump from the speaker,

telling us the trouble was farther back. Pulling the sound i.f. and ratio-detector

tubes brought similar results. While replacing the sound i.f. tube in its socket,

we banged a hand against the sound take-off transformer (T201 in Figs

1 and 2) and for a brief moment, had all the volume anyone, including the downstairs

neighbors, could possibly want.

Tapping the transformer a few times made the answer obvious. Either the transformer

itself was intermittent or its connections to the printed board were broken. Applying

a little pressure on one side of the transformer can would make the audio section

work perfectly.

Normally, the set would have been pulled right to the shop, but, with the Series

on, the customer wouldn't hear of it. He had a one-track mind: "You gotta fix it

now," were his only words.

The circuit itself definitely couldn't be fixed in his home. What with a 100-watt

soldering gun, close working quarters, no replacement transformer, and a large,

irate customer, things could only get worse.

Remembering that the set worked when the transformer can was pushed away from

the sound i.f. tube, we wedged an empty matchbook between the can and the tube.

The set ran throughout the whole Series and, when we went up the following week

to pick up the set for a final shop repair, the customer was grateful to the extent

of a generous tip.

Once the set was in the shop, the rest was simple. With a low-wattage iron and

some low-temperature solder, the job was completed easily. One of the lugs of T201

in Fig. 2 had broken away from the board. Forcing the matchbook between the

tube and the transformer had pulled the broken connection together temporarily.

How Not to Repair

One bright morning a few weeks later we were delivering a chassis from the shop.

After installing it, hooking up the yoke, high-voltage lead, speaker, and "kine"

socket, there was no picture or sound - just a clear light-grey raster. A look inside

showed a 6DE6 in the video i.f. section was out. After trying two new tubes, neither

of which lit, we decided the fault had to be in the socket connection for the 6DE6

(V302 in Fig. 3) to the printed-circuit board. A quick check with

the ohmmeter showed that pin 4, the hot side of the filament, was not connected

to the board at all.

Resolder a socket contact to the board? Shouldn't be too difficult - after all

it isn't going to look good if this goes back to the shop again. So, with the 100-watt

gun available on the call, plenty of heat and solder were applied.

End result was that pins 2, 3, and 4 were shorted, along with a few other things.

Back to the shop we went, where careful use of a low-wattage iron failed to repair

the circuit. Because of the damage done by the 100-watt gun, the entire board had

to be replaced at a cost of some $22.00. This experience will not fade from memory

for some time.

Now, what should have been done? To begin with, this particular soldering gun

should never have been used: its wattage rating is just too high. Second, heat should

not have been applied for more than a few seconds at a time. The shorter the time

an iron is applied to any of these boards, the better. If you don't get a joint

to hold right away, give it a chance to cool, and then try once again.

Fig. 3 - With connection of pin 4, V302, broken,

a wire can be run to lug H.

Fig. 4 - For replacing a board-mounted component, the manufacturer's

suggestion works best: solder new part to loops made from the leads of the old part.

However, even with low heat, the entire approach would have been wrong. In this

case, what should have been done was to tack one end of a piece of hook-up wire

to pin 4 of the tube socket and the other end to the terminal marked H on the circuit

board (Fig. 3). This would have eliminated the risk of hurting other wiring

on the board - and it's a lot easier to make this kind of connection than it is

to resolder a tube socket to a printed-circuit board.

In some vertical chassis, broken connections may be caused by flexing the chassis

while handling. Bending a board may place enough strain on it to break a connection

or two. Sometimes a board will snap right in half. While this can happen in any

set, it is more common in those that use the vertical layout. Remember this and

proceed with due caution.

Small-Component Problems

One day in the shop when we were still in the groping stage, we had a little

discussion on how to replace a small component like a resistor or capacitor on a

printed-circuit board. Each one of us had a different idea on how the job should

be. done. One of the technicians felt that he should unsolder the component from

the circuit, removing it completely, and then install a new part. Another figured,

just cut the old part out, and tack in a new one. Well, that sounded reasonable,

so we tried it and learned another way of how not to do things.

Getting the old part out was child's play. Two snips with a pair of diagonal

cutters and the job was done. Then it came time to tack the new one on. This wasn't

quite so simple. By the time we got things hot enough to do any tacking, there wasn't

any solder left on the contact we were soldering to.

Finally someone came up with a radical notion - he got hold of a copy of the

manufacturer's instruction manual! Believe it or not, their way was best. First,

said RCA's book (Fig. 4A), cut the part in half. We did. Next, with pliers,

crush the remaining halves (Fig. 4B) until only the leads remain. This leaves

the longest possible length of wire. Then bend a loop (Fig. 4C) in the end

of each lead. Interwind these with the leads from the new part and resolder, holding

a pair of long-nose pliers on each lead between the board and the point being soldered

(Fig. 4D). This approach worked, and no one has come up with a better method

as yet.

This incident just covered may seem like making much of an obvious point, but

the moral is important. Why learn the hard way when you don't have to? Manufacturers'

literature has its value.

One time we ran into a set whose picture would go on and off. The raster would

stay put, but the video signal wouldn't. Even walking across the room was enough

to knock it off. After getting the set on the bench, we started to trace back through

the video strip with a scope. Jarring the chassis now and then to induce the intermittent

symptom, we finally got to the point where the video signal was disappearing.

Fig. 5 - If it becomes necessary to unwind a wrap-around,

solder less connection, always reconnect it with solder.

You've seen the "wrapped-wire" connections (Fig. 5) on a printed-circuit

board? That's where the trouble was. Some technician who had once worked on the

set evidently unwound one of the connections at one time or another, probably while

making a resistance check. The only trouble was that he just didn't bother soldering

it when he finished - just wrapped it back around the terminal and gave it a little

squeeze with a pair of pliers. Unfortunately, that was the wrong way.

When these connections are made at the factory, they are tightly spun by a machine

that wraps the wire around the pin with great force. The result is such an effective

and reliable electrical bond between the wire and the terminal that solder is unnecessary.

However, you cannot duplicate this effect. Any time you open one of these connections,

you must solder it or face the equivalent of a cold-solder joint.

Another technique found to be a big help is the use of a set of test sockets.

Of course such aids were available and worthwhile before many of us ever saw printed

boards, but these tube-socket adapters are particularly handy for some printed sets

where tube-socket pins may not be too much in the clear. All you have to do (Fig. 6)

is pull the tube, plug in the test socket, and then plug the tube into the adapter.

What technician can forget the first time he had to replace a board-mounted i.f.

transformer? It might have been a discriminator or ratio-detector can as well, since

most of these are fastened to the board with lugs that also serve as the transformer

terminals. We went right ahead - heated up the lugs one at a time and, using a pair

of pliers and a screwdriver, managed to pry them into an upright position. It only

took 45 minutes - plus another three quarters of an hour to clean up the damage

that resulted when the screwdriver slipped. There had to be a better way! At that

rate, you could only handle about four jobs a day.

Fig. 6 - Where accessibility is a problem, the test adapter

inserted in a tube socket will permit convenient measurements without serious disassembly.

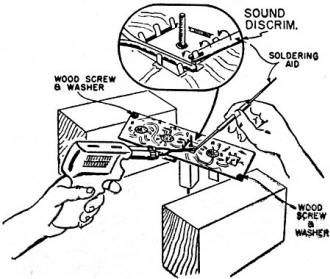

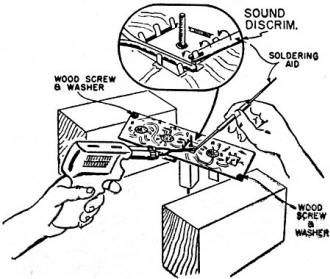

Fig. 7 - Soldering aid helps manipulate lugs of a transformer

can that must be removed. Support for board also helps.

On the next transformer replacement, a soldering aid with one notched tip was

used, as shown in Fig. 7. The tip not only makes it much easier to manipulate

the lugs while disconnecting them, as illustrated by the magnified view, but the

better grip it provides appreciably reduces the hazard of an accidental slip. Re-soldering

goes much faster and the rest is easy. Slip the defective can out and drop the new

one in. Just make sure the lugs are lined up right, then bend them back and re-solder.

You won't believe it, but there are four ways to patch up a break in a printed

circuit - and they all work. Of course, some ways may take a lot longer than others.

Here they are, in order of difficulty: First, you can just melt on some solder to

bind the break. This works fine - if you don't melt enough to run into a nearby

circuit. After a couple of tries we gave this up. Instead you get a printed-circuit

repair kit. This works but was given up because it takes quite a bit of time.

The next two methods, however, are practical. If you only have a small break,

get a short piece of bare wire and lay it across the break. A small drop of solder

on each end and the job is done.

If the break is large or a fairly long section of wiring has raised from the

board, cut out the damaged section completely and replace it with regular hook-up

wire.

If you haven't done much work on printed-wire circuits or haven't had good results

with the work you have done, these experiences may come in handy. Actually there

are just a few general points to remember, and most of them apply to any service.

There are right and wrong ways of doing things. When you do a job the right way,

you save time and money. Nobody has to tell you what can happen if you do things

the wrong way. Take your time with repair situations you haven't run into before.

Decide what to do before you start, not after you've already begun to do what may

be the wrong thing. Use a low-heat iron and a lot of care. After a while, you won't

be saying, "Who wants 'em?" because you will.

|

By Chester S. Lawrence

By Chester S. Lawrence