|

April 1969 Electronics World

Table of Contents

Table of Contents

Wax nostalgic about and learn from the history of early electronics. See articles

from

Electronics World, published May 1959

- December 1971. All copyrights hereby acknowledged.

|

As with most technologies

that have been around for decades, the fundamentals of crystal filters have not

changed with time. Materials and methods have changed, of course, but the equivalent

lumped element model (using resistors, capacitors and inductors) of a crystal filter

is essentially the same today as it was in 1969 when this article appeared in

Electronics World magazine. Open a first semester electronics circuits

textbook and the chapter on crystals will look much like this piece by Mr. Robert

Kent, of Damon Engineering. The use of crystal had a profound impact on filter design

because their extremely high "Q" factors permitted very sharp band edges for rejecting

nearby unwanted signals. Relatively low power handling and high insertion loss prevents

them from being used in receiver front ends requiring high sensitivity, but they

work miracles in IF (intermediate frequency) and baseband circuits after a stage

or two of signal amplification has occurred.

Crystal Filters

The author received his B.S. from Moore School of Electrical

Engineering, University of Pennsylvania, in 1950 and his M.S. in electrical engineering

from MIT in 1952. From 1952 to 1960, he was a staff member of MIT's Research Laboratory

of Electronics, participating in the development of missile guidance and electronically

scanned radar systems and in the design of a satellite gravitational red-shift experiment.

He has been with Damon since 1961 where he has been active in the design of quartz

crystal devices. He was named to his present post in 1968 and is now engaged in

the development of monolithic piezoelectric devices. He is a member of IEEE, Eta

Kappa Nu, Sigma Tau, Tau Beta Pi, and is an associate of Sigma Xi. He holds a

patent in the

area of phased arrays employed for missile guidance.

By Robert L. Kent / Engineering Manager, Electronics Division, Damon Engineering,

Inc.

Like other electronic components, crystal filters shrank physically when performance

and reliability improved. They offer users the maximum in stability and selectivity;

are favored in military, commercial applications.

Fig. 1. The equivalent circuit of a 10-MHz quartz crystal.

Fig. 2. The unbalanced half-lattice uses two crystals and

is building block for more complex filter configurations.

In the beginning, crystal filters could only be used in equipment where size

and weight were of little consequence. After World War II, weight and volume went

down while performance and reliability went up an order of magnitude. Now there

is a monolithic crystal filter which again cuts size and costs, has greater reliability,

and better temperature stability.

Crystal filters are used wherever the bandwidth occupied by a desired signal

is no more than a few percent, preferably no more than a few tenths of one percent,

of the operating frequency. Extremely narrow bandwidths are attainable because of

the inherent high "Q" of the quartz resonator. A "Q" of 100,000 is as readily obtainable

with a quartz crystal at 10 MHz as a "Q" of 100 with an LC resonant circuit.

High-frequency crystal filters have made a major impact on h.f. narrow-band communications.

System performance characteristics have been improved and complexity reduced through

the use of single-conversion receiver designs employing crystal filters. A more

recent application is in the area of frequency synthesis, where crystal filters

are used to clean out spurious signals caused by mixing and other non-linear synthesis

operations.

What Users Should Know

Before discussing "why" and "how" an engineer should select and use a crystal

filter, it is worthwhile to examine very briefly some filter designs. As previously

stated, crystal filters are narrow-band devices. They are used to select, or reject,

a very narrow frequency band out of a broad spectrum. Quartz crystals provide the

required selectivity when used in resonant circuits in conjunction with capacitors

and inductors.

The most common equivalent electrical circuit of a quartz crystal is shown in

Fig. 1. Shunt capacitance, C0, limits the bandwidth. Similarly,

the series resistance, R, along with temperature stability, places a lower limit

on practical bandwidths.

To obtain a symmetrical attenuation characteristic in a crystal filter, the shunt

capacitance of the crystals is often "balanced out" by means of bridge networks.

The unbalanced half-lattice (Fig. 2) is commonly employed for this purpose,

and becomes the building block with which more complex crystal filters are assembled.

Fig. 3 - A single hybrid transformer can be used to serve

two filter sections in this circuit.

A six-crystal filter is shown in Fig. 3. Note that a single "hybrid" transformer

can serve two of the filter sections.

The number of crystals which the filter uses is usually determined by 'the "shape

factor," i.e., the required selectivity. The shape factor is a ratio of bandwidths

measured at two different attenuation levels, such as -60 dB and -3 dB. The shape

factors for Butterworth (maximally flat) filter designs are listed in Table 1. Other

designs optimize such characteristics as group delay uniformity or phase linearity

for a specified shape factor or the number of resonators.

The range of 3-dB bandwidths obtainable with high-frequency (1-36 MHz) fundamental-mode

crystal filters is typically 0.005 percent to 2.0 percent of center frequency. Best

performance and lowest cost are obtained by favoring fractional bandwidths between

0.01 percent and 0.5 percent.

Monolithic Crystal Filters

Table 1. Shape factors for Butterworth (maximally flat) filters.

Table 2. Typical terminations for monolithic crystal filters.

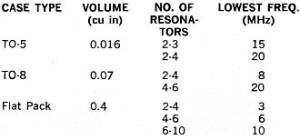

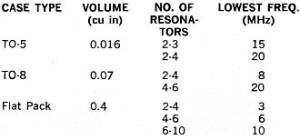

Table 3. Case sizes for monolithic crystal filters.

Conventional crystal filters are composed of discrete crystal resonators, inductors,

and capacitors with their electrical interconnections. In a monolithic crystal filter,

the electrical coupling components and connections are replaced by an elastic coupling

medium, namely the quartz plate itself. A monolithic filter consists of a single

wafer of crystalline quartz into which are deposited two or more pairs of electrodes,

as shown in Fig. 4. Each region between a top and bottom electrode becomes

a resonator, with the area of vibrational activity extending outward for a small

distance beyond the electrode region. The degree of elastic coupling between adjacent

resonators is a function of the distance between electrode pairs.

The monolithic filter works this way: A vibration is set up (piezoelectrically)

across the crystal's input resonator by the application of a high-frequency electric

field. This vibration is coupled elastically to successive resonators until it finally

reaches the output resonator. There, the mechanical vibration is transformed by

the piezoelectric effect back into electrical energy.

The electrical characteristics of monolithic crystal filters are comparable to

those of their conventional ancestors. The size and complexity are much reduced,

however, resulting in a device that is more reliable and costs less. At 21.4 MHz,

for example, a four-resonator monolithic filter housed in a low-profile TO-5 transistor

case occupies only 1/60th of a cubic inch and can be bought in large quantities

for less than $10 each. By employing these devices with other integrated circuitry,

a complete high-gain narrow-band monolithic i.f. amplifier can be packaged in a

volume of 1/33 cubic inch.

Considerations Affecting Cost

The cost of a crystal filter can range from less than ten dollars to several

hundred dollars. The major factors determining price are:

a. Quantity required - the multiplicity of parameters makes standardization of

models impossible, with few exceptions. The engineering cost associated with a new

design is normally amortized over the number of units purchased.

b. Complexity (number of crystal resonators) - determines assembly and alignment

time as well as materials cost.

c. Degree of difficulty and special testing requirements - by avoiding the extremes

shown on design charts, and by limiting the specification requirements to what is

really needed, this cost element can be minimized.

Fig. 4. Monolithic filter consists of a single quartz wafer on which two

or more pairs of electrodes are deposited.

Choosing the Filter

A conventional 4-pole crystal filter used in Talos missile system,

with a center frequency of 2.5 MHz, 1.5-kHz bandwidth.

An assortment of monolithic crystal filters covering the frequency

range of 3-30 MHz and bandwidths of 500-15,000 Hz.

A rather common error in the design of electronic systems that employ sophisticated

components is to leap first and look later. If the salient characteristics and limitations

of the major components can be borne in mind from the earliest phases of the design,

a better and more economical system will result.

Therefore, a designer who is planning to employ crystal filters in his system

should consider the following areas:

a. Fractional Bandwidths:

For best performance and lowest cost, choose intermediate frequencies so that

the required bandwidths fall between 0.01 percent and 0.5 percent of center frequency.

At frequencies from 35 MHz to 70 MHz it is necessary to employ third-overtone resonators,

and the bandwidth limits become 0.005 percent and 0.05 percent of center frequency.

Overtone crystal filters are more costly than fundamental-mode filters; moreover,

it is usually possible to obtain the same bandwidth at a lower center frequency

with fundamental crystals.

b. Stability with Time and Temperature:

Quartz crystals are extremely stable devices. Typical aging rates of high-frequency

filter crystals are 5-10 parts per million per year. The variation of frequency

with temperature is typically (maximum) ±10 parts per million from 0°C

to 50°C, or ±20 parts per million from -40°C to 100°C. For bandwidths

greater than 0.1 percent of center frequency, the effects of other discrete components

upon the aging and temperature characteristics can be greater than effects of the

crystals themselves. The system configuration and filter bandwidths should be chosen

to minimize the effects of time and temperature upon system performance.

c. Filter Terminations:

Conventional (non-monolithic) crystal filters normally contain tuned transformers

and inductors, making it a simple matter for the filter designer to shift from the

characteristic terminating impedance of the filter to whatever value the user chooses

to provide. There are, however, several points worthy of consideration in this regard:

1. If a pure resistive termination is specified, the shunt capacitive reactance

should be at least ten times greater than the terminating resistance. 2. A tolerance

of ±5 percent on the terminating impedance is normally required in order

to obtain best performance. If this is inconvenient for the user to provide, resistive

padding can be incorporated into the filter. The result is an increase in insertion

loss. 3. A reactive terminating impedance, such as 20 picofarads in parallel with

50 ohms, can usually be accommodated in the design. At 30 MHz, for example, a capacitance

in parallel with 50 ohms might be specified as 20 ±10 pF, since 10 pF has

a reactance of about 500 ohms. 4. At frequencies above 10 MHz it is generally desirable

to specify a low terminating resistance such as 50 ohms. This minimizes the detuning

effects of parasitic capacitance. 5. Monolithic crystal filters usually do not contain

tuned inductors or transformers. In order for the user to exploit fully the size

and cost advantages of the monolithic filter, he must design external circuitry

to present the terminating impedance required by the filter. Typical values of terminating

resistance for monolithic filters are given in Table 2. The impedances shown are

for filters operating in the h.f. band.

Fig. 3 - A single hybrid transformer can be used to serve

two filter sections in this circuit.

d. Other Specifications:

1. Shape factor, more than any other characteristic, determines the number of

resonators required. A Butterworth (maximally flat) design provides 6 dB attenuation

at twice the 3-dB bandwidth for each independent resonator, or pole. A six-pole

Butterworth filter, for example, would yield a shape factor from 36 to 3 dB of 2:1.

A Chebyshev (equi-ripple passband) design will be steeper in cut-off, while a Bessel

(maximally flat time delay) design will provide a considerably more gradual attenuation

characteristic. 2. Rejection of spurious responses. Inharmonic overtone responses

of filter crystals can produce undesired" spurs" at frequencies removed from the

passband. Spurious responses generally appear in wider bandwidth filters, especially

those comprising only one or two cascaded sections. Inharmonic overtones of high-frequency

crystals typically occur at frequencies 1-3 percent above the fundamental resonance.

This fact can sometimes be advantageous in the selection of a local oscillator frequency.

3. Ultimate attenuation (approximate rule of thumb): narrow crystal filters - 30

dB per section; wider crystal filters - 20 dB per section; monolithic filters -

20 dB per resonator below 10 MHz, 15 dB per resonator above 10 MHz. 4. Insertion

loss: 1 dB to 6 dB, increasing as either the upper or the lower bandwidth limit

is approached. 5. Ripple in passband: typically ±0.5 dB over wide temperature

ranges; 0 dB for rounded-nose (Gaussian or Bessel) types. 6. Volume: conventional

crystal filters - 1-24 cubic inches. Size increases with number of resonators and

with decreasing frequency. Monolithic filters - see Table 3.

Fig. 4 - Monolithic filter consists of a single quartz wafer

on which two or more pairs of electrodes are deposited.

Looking Ahead

Within the next five years, manufacturing techniques will be developed for large-scale

production of sophisticated monolithic quartz filters. Commercial usage of monolithic

filters in home entertainment and ham radio will become economically feasible, resulting

in a large market for the devices.

Because of its small size, the monolithic filter will be treated more like a

miniature integrated-circuit module than a complex subassembly. Unit prices as low

as $3-$4 are not inconceivable.

Another area of increasing interest is the use of new piezoelectric synthetic

crystal materials in filters. Zinc-oxide and other metals are currently being explored

as possible resonator materials. The attraction of these materials stems from the

fact that greater piezoelectric coupling coefficients exist than with quartz. Sophisticated

filters with fractional bandwidths of 1-10 percent could then be achieved in the

high-frequency range, closing the gap that currently exists between quartz crystal

devices and LC filters.

|