|

November 1969 Electronics World

Table of Contents

Table of Contents

Wax nostalgic about and learn from the history of early electronics. See articles

from

Electronics World, published May 1959

- December 1971. All copyrights hereby acknowledged.

|

Galvanic corrosion is

a potential problem (get it - potential?) for just about any scenario where two

metals of differing nobility (position the galvanic table) come into contact

with each other. This 1969 Electronics World magazine article explains

corrosion as an electrochemical process akin to electronics, involving anodes,

cathodes, electrolytes, and electron flow, particularly in marine environments.

Galvanic corrosion occurs with dissimilar metals like zinc (anode) and copper

(cathode) in water, accelerated by oxygen depolarizing the cathode. Factors

include galvanic/activity series rankings, electrolyte pH, chloride content,

humidity, and oxygen differentials causing pitting. Electrolysis arises from

stray currents or voltage drops in boat wiring; local-cell action from metal

impurities. Prevention strategies include selecting compatible metals, using

zinc sacrificial anodes, or impressed-current cathodic protection systems with

reference electrodes and platinum anodes to counter galvanic action. Instruments

like pH meters, voltmeters, and chloridometers aid diagnosis, emphasizing

electronics technicians' role in marine corrosion control.

The Electronics of Corrosion

Fig. 1 - A portable battery-operated pH meter that is used by

electronics technicians who specialize in marine work.

By William P. Ferren, Ph.D.

F.A.I.C.* /Associate Professor of Chemistry

Wagner College, N.Y.

The role played by electronics in causing and/or minimizing corrosion, especially

as related to marine environments, is explained. The various types of corrosion,

as dependent on the environment (electrolyte) and the galvanic arrangement (dissimilar

metals), are discussed by author.

The fundamental action in corrosion is electronic in nature. This electro-chemical

process holds true whether the corrosion takes place in an air environment, in the

water, or in the interface between the two. Indeed, much of the terminology used

by corrosion scientists and engineers reflects this. Such terms as anode, cathode,

electrolyte, ionization, current, potential, voltage and e.m.f. are as familiar

to the corrosion engineer as they are to the electronics technician.

Galvanic Corrosion

Similarly, the classical explanation of the phenomenon of corrosion is readily

understandable by those in electronics. Any metal placed in a water solution will

begin a process of dissolution. If we take two unlike metals such as zinc and copper,

place them in water, and wire them together external to the water electrolyte, we

have created conditions whereby corrosion can take place. It is from this simple

galvanic cell that the particular type of corrosion that occurs when two dissimilar

metals are exposed to a common electrolyte and are physically connected externally

derives its name - galvanic corrosion. The zinc atoms in contact with the water

lose electrons and enter the water as positively-charged zinc ions. The electrons

released by the ionized zinc atoms will travel through the wire from the zinc anode

to the copper cathode. In the electrolyte, the zinc ions will travel toward the

copper cathode. But these zinc ions never reach the copper cathode because of a

chemical reaction that has been taking place within the electrolyte. The water atoms

have also been ionizing; the hydrogen atoms in the H20 combination become

positively charged hydronium ions by giving up electrons, and negatively charged

hydroxyl ions by gaining electrons. The positive hydronium ions seek to regain their

lost electrons and take them from the copper cathode which by now has an abundance

of the electrons released by the zinc atoms when they ionized. Thus, the hydronium

ions become hydrogen molecules when they achieve balance. The negative hydroxyl

ions share their excess electrons with the zinc ions and here, too, balance is achieved.

If nothing further happened ill this system, the galvanic corrosion process would

cease for the hydrogen atoms clustered around the copper cathode in the form of

hydrogen gas (polarization) would effectively shield it from the electrolyte. But

oxygen becomes involved and combines with the hydrogen atoms to form water -Ho()

-once more. This action exposes the copper cathode to the electrolyte, thereby re-

establishing the electrical circuit, and permitting the corrosion process to continue.

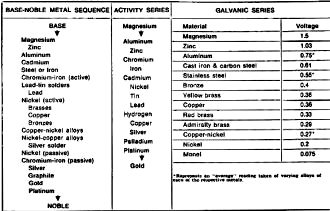

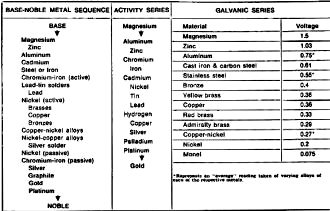

Table 1 - Listings of base-to-noble metal sequence, activity

series, and galvanic series. Base metals at the top of the list function as the

anode when used with metals lower in the series (more noble), and are subject to

corrosion. The activity series, with hydrogen gas as the arbitrary reference, indicate

the relative inertness of reactivity of metals. The reactive elements are above

hydrogen while the inert elements are below. The galvanic series, the most used

series in considering the electronics of corrosion, indicate voltage readings recorded

between the indicated metal and a silver/silver-chloride reference electrode while

immersed in a relatively unpolluted sea-water electrolyte.

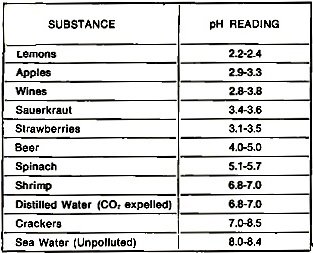

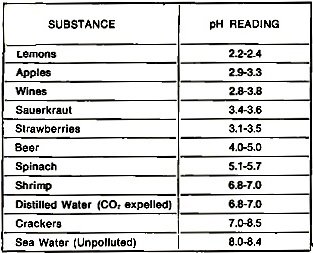

Table 2 - Representative pH readings of familiar substances.

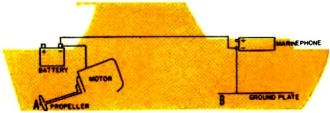

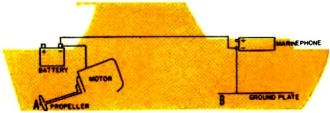

Fig. 2 - A frequent cause of electrolysis corrosion in boats

is the voltage-drop condition that exists between the propeller (A) and the ground

plate (B) due to the long wire run from the negative terminal of the battery to

marine phone.

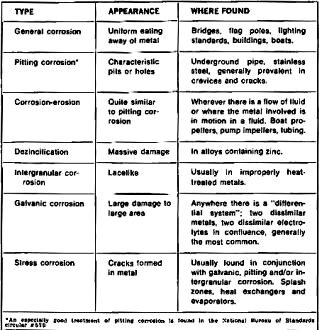

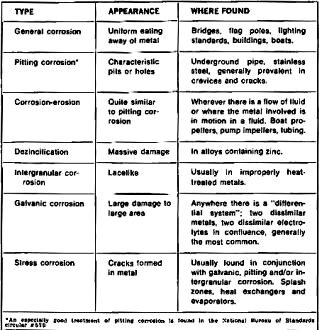

Table 3 - Characteristics of different types of corrosion.

Fig. 3 - Buchler's Chloridometer, an instrument that can be used

for determining the possibility of corrosion by measuring the amount of chloride

present in water.

Rating Galvanic Action

Traditionally, corrosion engineers and scientists while recognizing that an electrolyte,

whether it be a water solution or highly humid air, is necessary for corrosion to

occur, have tended to concern themselves more with the proper choice and treatment

of metals existing in a system to impede or halt corrosion. The base-noble metal

sequence in Table 1 is one of three common listings which have been compiled as

an aid to choosing combinations of metals that will reduce the possibility of galvanic

corrosion. The recommended practice is to either choose identical metals or metals

close together in the base-noble series if they are to be in physical contact with

each other while exposed to a common electrolyte. The farther apart two metals are

from each other in this series, the higher the potential difference between the

two and, therefore, the greater the possibility of corrosion. The same philosophy

applies to both the activity and galvanic series (Table 1). In each of these three

charts, the anodic metal - the one which will suffer the structural corrosion damage

- is at the top, the cathodic metal. The one which will not be affected by the corrosive

process - is at the bottom. The farther apart any two metals are in any of these

series, the stronger the galvanic cell.

The galvanic series is probably the most used series in considering the electronics

of corrosion. This particular galvanic series was predicated on a sea-water electrolyte

and using a silver/silver-chloride reference electrode. Just as in assessing antenna-gain

figures, one must know exactly what the reference unit is. Readings based on a calomel

electrode or a metal electrode would give entirely different readings than those

listed for the galvanic series in Table 1. Fortunately, the silver/silver-chloride

electrode is gradually becoming the standard. As mentioned above, the metal at the

top of the scale will become the anode, the metal at the bottom the cathode. In

the preceding zinc-copper explanation, for instance, the zinc was anodic, the copper

cathodic. Similarly, copper would become the anode when coupled to nickel in a two-

metal, electrolytic, physically connected system. Measurements performed by the

author using the Simpson 313 v.o.m. with a silver/silver-chloride electrode yielded

different values. The reason for the variance was that the author's sea-water samples

came from the highly polluted New York port area while the readings for the galvanic

series in Table 1 were based on relatively unpolluted sea water. In addition, the

New York port area waters have a certain percentage of fresh water introduced by

the Hudson River and other tributaries. The sea water used for the galvanic series

in Table 1 is relatively unpolluted and has no meaningful fresh water content. Thus,

we see that a difference in electrolyte will make a difference in the rate of corrosion.

Indeed, the entire study of corrosion might be said to be a study in differences:

differences in metal, in electrolyte, in - as we will see later - oxygen concentration

in the electrolyte, even differences in size between the anode and cathode involved.

In other words, the corrosion system is a differential system.

Corrosion vs. Electrolyte pH

Just as there are instruments to read the differences in electronic concentration,

i.e., potential (the voltmeter) and to read the flow of electrons (ammeter) , so

also is there a meter to read the active concentration of ionized hydrogen atoms

in a water solution. This is the pH meter and might be regarded as a high-impedance

voltmeter used in conjunction with a special permeable glass probe and a reference

half cell. While the basic function of a pH meter is to determine the active acidity

or alkalinity of a solution, most have an e.m.f. position to read voltages (instruments

without the e.m.f. position may be used to read voltages by substituting 0.06 volt

per pH unit) . Probably the handiest pH meter for the electronics technician would

be the unit made by Analytical Measurements (Chatham, New Jersey). This instrument

(Fig. 1) is portable and battery-powered which permits it being taken "on the scene"

which, in most cases, is a virtual necessity.

The pH meter differs from the voltmeter or ammeter in that it reads "backwards."

While the voltmeter will read higher on the scale when the voltage difference present

is relatively higher, and the ammeter will give a higher indication when the current

is high, the pH meter reads inversely, i.e., the lower the ionized-hydrogen activity,

the higher the pH reading; the higher the ionized-hydrogen activity, the lower the

pH reading. As mentioned above, the pH meter's basic function is the determination

of the active acidity or alkalinity of a solution. Analytical chemists decided that

the more acid a solution the lower the reading, the more alkaline the solution the

higher the reading. The center point of the 0-14 scale -7- was assigned to carbon

dioxide-free distilled water. Some representative pH readings of familiar substances

are given in Table 2.

In practical terms, the electronics technician embarking on corrosion control

will be concerned with only three electrolytes: sea-water, fresh-water, and high-humidity

atmosphere. Comparatively, unpolluted sea water has a pH reading from 8.3 to 8.7

on the 0-14-pH scale. Polluted sea water, such as found in the New York port area,

the Houston ship channel, and other areas in which industrial wastes abound, will

read from 6.0 to 6.6 or sometimes lower. The conclusion: pollution is acid. It follows

that the greater the pollution, whether in an air or water system or interface between

the two, the higher the corrosion possibility. For example, a ship or pleasure boat

with a galvanic arrangement (a metallic-differential system) of a bronze propeller

and a steel rudder and moored or operating in the relatively alkaline environment

of the open sea will not have anywhere the corrosion problem as the same ship moored

in, say, Brooklyn's highly polluted Newtown Creek. In other words, a change in the

electrolytic ecology in which the two dissimilar metals in the galvanic arrangement

find themselves is far more insidious and influential than is usually realized.

This influence of pollution also holds true of corrosion in an air environment.

Here, air with a relatively high percentage of humidity serves as the electrolyte.

The damper climates such as experienced in the Gulf of Mexico and Florida areas,

the Washington-Oregon area, certain portions of the Great Lakes, and, in fact, most

seaboard areas will provide ideal surroundings for corrosion. Couple this ideal

corrosion environment with air pollution and corrosion becomes a major economic

factor. Indeed, some statistics state that one-fifth of the world's annual production

of iron and steel is lost to corrosion. Table 3 lists the different types of corrosion;

their characteristics and where generally found.

Electrolysis Corrosion

A close relative to galvanic corrosion is the so-called electrolysis corrosion

or "stray-current" corrosion. This type arises when the voltage difference in a

corrosion system is not self-generated but is impressed externally. With the advent

of electronic equipment on boats, this kind of corrosion problem assumed increasing

importance. There are two basic areas here and they are both electrical in nature:

externally impressed voltages due to voltage drops in the boat's electrical system,

and cross grounding. Owing to the increasing prevalence of grounding the negative

side of the vessel's electrical system, this latter type is not encountered too

often except in older commercial vessels. The author has several case histories

in which propellers and other underwater metal boat parts have been destroyed in

a matter of weeks due to cross grounding. It is in this area of electrolysis corrosion

that the electronics technician is most usually involved ("I didn't have this corrosion

until you installed the radio!") and generally the villain of the piece is a voltage

drop. Nine times out of ten, a voltage-drop condition can be eliminated by using

the largest practicable size wire for power leads and by bonding all metal parts

of the boat to a common ground strap. This could be a length of strip copper laid

along the keelson with heavy wire or braid going from it to the various metals on

the boat. One common voltage-drop condition involving the marine phone ground-plate

is seen in Fig. 2. The best instrument for detecting voltage drops is one of the

new breed of high-impedance input, battery-operated e.o.m.'s with extra-long clip

leads. The check is made from each metal part to every other metal part and comparing

the power-on with the power-off reading. On land, another pair of leads - even longer

- with 12" to 18" spikes as the probes can be used for determining voltage drops

on buried pipe systems. Gas company officials claim severe corrosion damage to their

natural gas pipelines in the vicinity of electric train tracks despite the use of

high-efficiency magnesium sacrificial anodes.

Local-Cell Corrosion

The two types of corrosion so far discussed have been based on physically obvious

electrical circuits: two metals, a common electrolyte, a complete circuit. But what

causes the corrosion in, say, a metal post with absolutely no connection or relationship

to any other mass of metal? This kind of damage is clue to local-cell action. Just

as local action in a lead-acid storage cell, because of impurities in the electrodes,

can cause sulphation of the plates or the same local cell action can cause the disintegration

of the zinc casing of a dry cell, so also does this phenomenon cause the corrosion

damage in seemingly independent metal structures. One of the most familiar samples

of local cell corrosion is seen by the average person on automobile body parts such

as that shown in the photo on page 42. There are many reasons why these small local

cells are formed on the surface of a piece of metal: impurities in the metal itself,

orientation of the grains in the metal structure, imperfections on the surface,

stresses placed upon the metal when it is used in construction, imperfect homogeneity

in the manufacturing process and others. But in examining local-cell corrosion we

find the identical action taking place that occurred in galvanic corrosion; there

will be many minute anodic and cathodic areas. Each anode and cathode will, obviously,

be physically connected and will also be exposed to a common electrolyte.

Oxygen-Differential Corrosion

In local-cell corrosion, however, the appearance of the damage is different from

that caused by galvanic or electrolysis (externally impressed voltage) corrosion.

It has a characteristically pitted appearance. This pitting process can, however,

multiply and progress until the entire surface is corroded. This is seen in the

familiar "rust" on iron and steel. It is in the area of pitting corrosion that often

there is a merging into yet another form of corrosion: the oxygen-differential system

or the creation of a galvanic cell composed of the same metal in physical contact

but exposed to two different - but connected - electrolytes. The differences in

the electrolytes will be a difference in oxygen concentration.

The oxygen-differential system can be found where one part of a metal structure

is shielded or protected from the air or water while other parts of the same metal

are exposed to the electrolyte. Painting part of a structure and leaving part unpainted

is an invitation to corrosion. Barnacles on boat underwater metal parts will create

a situation where the metal directly underneath the barnacle will be exposed to

an electrolyte having less oxygen than the electrolyte in contact with the adjacent

metal. A simple thing such as the buildup of sand around the base of a metal piling

or post or even sand drifting onto part of a metallic structure can give rise to

the oxygen- differential corrosion system. One very unfortunate and, one might say

"treacherous," example of this type of corrosion may possibly take place under the

zinc sacrificial anodes installed to prevent corrosion. As the zinc corrodes in

its protective action, it will gradually leave a space between itself and the metal

to which it is attached. The electrolyte (water) in this space will have less oxygen

present than water in contact with the adjacent "protected" metal and oxygen-differential

corrosion may take place. This condition may merge into one in which the zinc anode

eventually becomes insulated from the metal part which it is supposed to protect

and galvanic corrosion can then take place between the no-longer-protected metal

and some other metal which is cathodic to it.

Oxygen, then, is another prerequisite to the corrosion process and as can be

expected, we find massive corrosion damage in the so-called "splash zone" or interface

between the air and water environments. The electrical activity of a corrosion system

will be at its highest where wetting and drying, i.e., alternate exposure to the

electrolyte and to the increased oxygen in the air takes place. If we add chloride

(the basic element that differentiates sea water from fresh water) to this system,

we find extensive corrosion damage. The emergent container - ship industry is haunted

by just this type of a problem. Containers, or rather more precisely, the fittings

that are used for moving these containers, may fail long before their projected

life expectancy. An inspection of metal structures along the waterfront of a port

city such as New York will also bear this out. Fig. 3 is a photograph of Buchler's

"Chloridometer," an instrument that can be used for determining the possibility

of corrosion by measuring the amount of chloride present in the water sample.

Anti-Corrosion Techniques

Probably the most common way to combat the ravages of the corrosion process is

by using sacrificial anodes. These are usually of zinc or zinc alloy and are interposed

between the anode and cathode of the galvanic corrosion arrangement and connected

to the anode. In effect, we are substituting a more efficient "battery" component

- the zinc anode -having a higher anodic capability which will dominate the prior

anode and thus protect it.

The true electronic means of protection, however, is the impressed-current approach.

This might be viewed as making an asset of a liability. We have seen that corrosion

can result from impressing an external current on the system (stray-current corrosion).

If we were to use the same concept, but reverse the polarity of the voltage generated

by a galvanic arrangement, we would find that the corrosion process would be effectively

halted. If, for instance, there were a 0.3-volt difference between a bronze propeller

and a steel rudder and these two metals were connected externally by metallic continuity

or, as is often the case, through bilge water we would have the ideal arrangement

for corrosion damage to the anodic rudder ( the bronze propeller being the cathode).

A 0.3 voltage of the opposite polarity impressed across the steel-bronze system

( the physical external connection would first have to be broken) should effectively

prevent corrosion damage to the rudder. The next logical step would be to bond all

the vessel's underwater metal parts together to form a common cathode and then introduce

a balance voltage of sufficient strength via an independent electrical anode so

that the galvanic action would be effectively balanced out. In effect, this system

weakens the anode-cathode relationship to a degree and can be done during the construction

of the boat by using identical metals or metals close to each other in the galvanic

series. This is the basic theory behind the impressed- current or "cathodic" protection

systems. I

t must be stressed that this form of electronic protection will not apply when

stray-current corrosion (voltage drops or cross groundings) or the so-called cavitation

or water-flow corrosion are involved. It is also of doubtful value in oxygen-differential

or area-differential corrosion systems. Even its forte, the halting of galvanic

corrosion, can sometimes be useless because of the difficulty of applying it. In

a case where steel nails are used to install aluminum siding, and there exists the

galvanic reaction between the steel and the aluminum (intense corrosion would be

seen in the aluminum in the vicinity of the nails), there would be no advantage

in attempting impressed current protection methods. The proper practice, of course,

would be to use aluminum nails as a first choice with galvanized-steel nails as

a second. Similarly - although impressed-current philosophy could be made to work

- the corrosion potential between an aluminum lightning rod and a copper grounding

wire would most sensibly be eliminated by using a copper lightning rod or aluminum

grounding wire. In marine work, a like case is seen in marine antennas constructed

of aluminum tubing being fed by a copper transmission line. The new fiber glass

whips with imbedded copper-wire elements have done much to eliminate this common

corrosion problem.

This is not to say that the impressed-current systems are not good. Far from

it. Besides their obvious use in the marine area (oil tank ships with this system

can be constructed with lighter scantlings - on the order of 5-10% - which means

construction costs are less), the protection of pipeline systems can be accomplished

by connecting the pipe to a negative d.c. source and the positive d.c. to electrodes

buried at proper intervals in the ground. The current flow in such a system is from

0.3 to 0.5 milliampere per square foot of pipe, and the voltage will range from

1.5 to 30 volts depending on the resistance of the system.

The impressed-current systems used on boats and ships are all basically the same.

They consist of three elements: a reference electrode, a control unit, and the anode

which introduces the proper current and voltage against the underwater metal parts

to be protected. The reference electrode monitors the amount of protection given

to the boat's underwater metal parts (bonded together to form a common cathode)

and in turn the control unit compares this reference voltage produced by the reference

electrode to the pre-set voltage of the control unit. The output of the controller

is applied to the anode. Since the corrective current is externally ap- plied and

because deterioration of this anode would serve no useful purpose, it is usually

made of one of the metals of the platinum family. Care must be taken that the anode

voltage is not set too high as this may be of doubtful benefit and, in fact, may

cause damage.

In summary, we have progressed from the electronic action which is the basis

for corrosion to an electronic solution to combat this damaging process. Even the

few digressions, such as the discussion of pH, were related to the electro- chemical

phenomenon which is corrosion. Knowledge of such things as pH, chloride content,

and so-on are, of course, valuable to the marine electronics technician. Too often,

for instance, one will find that the malfunction of a transmitter or receiver or

depth-sounder isn't due to something wrong with the unit itself, but to such things

as improper supply voltage, r.f. interference, poor antenna placement, etc. The

same applies to ascertaining the reasons for corrosion. The technician must be prepared

(and this dictates proper instrumentation) to investigate the ecology which surrounds

the vessel on which he has installed or is maintaining electronic equipment. When

he knows the facts of the marine environment, then he'll have intelligent, helpful

answers for the man who says:

"I didn't have this corrosion problem until you installed the radio...!"

*The author is consultant to Marine Surveys Co., Inc., Stillwell & Gladding

(an independent testing laboratory), and Marine Container Equipment Certification

Corp. He recently hosted an industry conference on corrosion problems at Wagner

College's Staten Island (N.Y.) campus.

|