|

August 1969 Electronics World

Table of Contents

Table of Contents

Wax nostalgic about and learn from the history of early electronics. See articles

from

Electronics World, published May 1959

- December 1971. All copyrights hereby acknowledged.

|

"Almost simultaneously as

they are flashed before the NASA officials, the signals bearing in minute detail

the progress of Apollo 11 will be broadcast internationally, allowing the entire

world to share in the drama of the manned lunar landing." Such a statement meant

something much different in 1969 than it does today when this article appeared

in Electronics World magazine. Back then, it meant news and

government organizations with the required equipment would be able to receive the

information and then disseminate it via secondary media sources like TV, radio,

magazine, and newspaper. Today it means a real-time feed is available on the Internet

for anyone with a network connection to access. This article was written in a forward-looking tone since the August issue would

have gone to press sometime in July, before Apollo 11 even launched (note the

reference to the planned date of the 16th). The entire mission proceeded without

a major incident, as presented here.

Aside: Having been a follower of space exploration

and aerospace technology, I have read many articles on rockets and space probes.

I have been building

model rockets since the late 1960s and even got a certificate

from Estes for launching my Alpha rocket on July 20, 1969, the date when

Apollo 11

landed on the moon. Surprisingly, now that I am reminded of it with this article,

Estes never offered a model of the Lunar Lander. They did have a

Mars Lander, which like the Lunar Lander used a set of shock-absorbing legs

to handle the impact of its rocket-assisted vertical landing. The Estes model did

not look much like the eventual

Mars Viking lander, other than the shock-absorbing legs. Anyway,

the point of my discussion here is that long before SpaceX and Blue Origin were

accepting kudos for accomplishing vertical spacecraft landings, NASA pulled it off

on the Moon beginning in 1969 and on Mars first in 1976. Sure, the gravity is much

less there (17% on the Moon, 38% on Mars), but technology and computer processing

power was much less then. Aside: Having been a follower of space exploration

and aerospace technology, I have read many articles on rockets and space probes.

I have been building

model rockets since the late 1960s and even got a certificate

from Estes for launching my Alpha rocket on July 20, 1969, the date when

Apollo 11

landed on the moon. Surprisingly, now that I am reminded of it with this article,

Estes never offered a model of the Lunar Lander. They did have a

Mars Lander, which like the Lunar Lander used a set of shock-absorbing legs

to handle the impact of its rocket-assisted vertical landing. The Estes model did

not look much like the eventual

Mars Viking lander, other than the shock-absorbing legs. Anyway,

the point of my discussion here is that long before SpaceX and Blue Origin were

accepting kudos for accomplishing vertical spacecraft landings, NASA pulled it off

on the Moon beginning in 1969 and on Mars first in 1976. Sure, the gravity is much

less there (17% on the Moon, 38% on Mars), but technology and computer processing

power was much less then.

Communications on the Moon

When men first walk on the Moon's surface, they

will be able to communicate by v.h.f. radio with each other and with the command

module orbiting overhead. They will also be directly in touch with Earth by microwave

radio and will be able to send back live television pictures over the vast translunar

distance. When men first walk on the Moon's surface, they

will be able to communicate by v.h.f. radio with each other and with the command

module orbiting overhead. They will also be directly in touch with Earth by microwave

radio and will be able to send back live television pictures over the vast translunar

distance.

When Christopher Columbus sailed his way into history almost five centuries ago,

he severed contact with civilization for the duration of his voyage. Except to the

90 sailors who manned the expedition, Columbus' trials and triumphs, including his

discovery of a new world, remained unrevealed until his return.

On July 16, if NASA plans proceed on schedule, a new breed of explorers will

embark on a voyage that will rank them alongside Columbus in the annals of mankind's

great adventures. Yet, although their trip will traverse a distance 45 times that

of Columbus' route, they will not, except for short intervals, face isolation from

the civilization they leave behind.

A stream of electronic signals will flow from the two Apollo 11 spaceships.

Gathered in by a world-wide tracking network, they will be relayed instantly to

the NASA Manned Spacecraft Center in Houston, Texas, where a cadre of mission controllers

will be supporting astronauts Neil Armstrong, Edwin Aldrin, and Mike Collins as

they fulfill man's centuries-old desire to escape the confines of his native planet

and alight upon another body in the Universe. A sharp contrast to the plight of

Columbus, who had to do his own piloting and mission planning virtually alone.

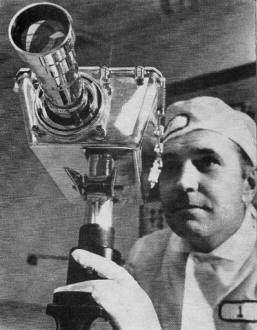

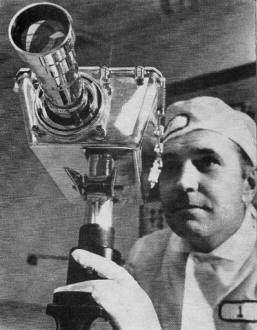

The 7-lb TV camera that will send live TV pictures from Moon.

Almost simultaneously as they are flashed before the NASA officials, the signals

bearing in minute detail the progress of Apollo 11 will be broadcast internationally,

allowing the entire world to share in the drama of the manned lunar landing.

Apollo 11 will begin from Cape Kennedy when a Saturn 5 rocket, thundering

aloft with 7.5 million pounds of thrust, drives the Apollo command / service (CSM)

and lunar (LM) modules, as well as its own third stage, into earth orbit. After

less than two revolutions of the globe, during which the third stage and spacecraft

systems will be checked out, the rocket will re-ignite to propel the astronauts

on their way to a lunar touchdown.

Almost immediately after the translunar coast begins, the astronauts will separate

their CSM from the third stage, turn it around, and dock with the LM. They will

then extract LM from its adapter still attached to the rocket.

On the fourth day of the mission, as the CSM-LM combination swings around the

Moon, the CSM service propulsion system engine will fire to brake the docked spacecraft's

speed and allow them to be captured in lunar orbit. A second engine burn later will

circularize the orbit to approximately 60 nautical miles.

Then on the fifth day, astronauts Armstrong and Aldrin will transfer to LM from

the CSM through the docking tunnel and power up the lander's systems to check them

out. Following the checkout, Armstrong and Aldrin will separate LM from the CSM

and fire their descent engine to lower the LM orbit nearer the Moon. As they approach

closer to the lunar surface, they will begin terminal descent during which they

will fire the engine almost constantly, throttling its power to achieve a landing

in helicopter fashion.

On the Moon's Surface

The first order of business for Armstrong and Aldrin after the landing will be

to check out the LM systems to make certain everything is ready for the lift-off

that will return them to the CSM, piloted by Collins, in orbit around the Moon.

That accomplished, they will don their portable life-support system backpacks, depressurize

the LM, and open its door. Moments later, Armstrong will scale down the LM ladder

and step onto the lunar surface.

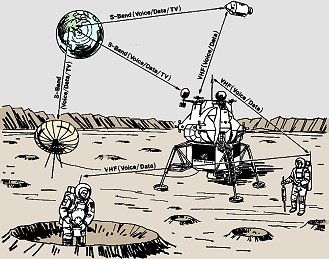

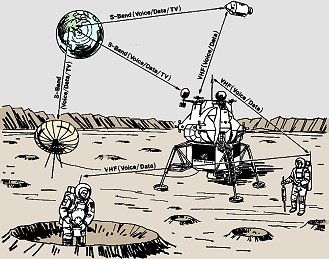

Astronauts on the Moon will use v.h.f. radio to communicate with

each other and S-band microwaves for Earth communications.

Armstrong later will be joined by Aldrin outside the spaceship as they begin

a modest exploration, staying within 50 to 100 feet of the LM. During this time

- about 2 hours, 40 minutes of the total 22-hour lunar stay will be spent outside

the spacecraft - the astronauts will stay in touch with one another, and with mission

controllers on Earth, using a compact extra-vehicular communications system (EVCS)

built by RCA.

The EVCS consists of a v.h.f. transceiver set in each astronaut's backpack. Although

each measures only 14" x 6" x 1 1/4" and weighs only 6.5 pounds, it contains two

AM receivers, two AM transmitters, either an FM transmitter or an FM receiver, plus

telemetry instrumentation to transmit astronaut biomedical data and status of the

spacesuit systems.

Use of an FM receiver in one EVCS unit and the FM transmitter in the other will

allow the receiver-equipped extra-vehicular astronaut (EVA) to serve as a radio-relay

point for voice and data between his partner and the LM. This arrangement has one

EVA transmit via FM (279 MHz) to the second, which converts the transmission to

AM (259.7 or 296.8 MHz) for relay to the LM communications systems. Both astronauts

can also transmit directly to LM via AM.

The LM, in turn, will convert the v.h.f. voice and data transmissions to u.h.f.

S-band microwave signals and transmit them to Earth on a carrier frequency of 2282.5

MHz.

The teaming of v.h.f. and u.h.f. S-band is characteristic of the entire Apollo

communications scheme, which must link two spacecraft to Earth and to each other,

and also make provision for astronauts exploring the Moon. S-band carriers are used

for spacecraft-to-Earth links for both LM and CSM, and v.h.f. will be employed for

communications between the two spaceships and for extra-vehicular activity on the

Moon.

In all cases, the S-band and v.h.f. can be converted to one another, providing

a number of communications paths to assure that everyone - the CSM, LM, and Earth

- remains in contact.

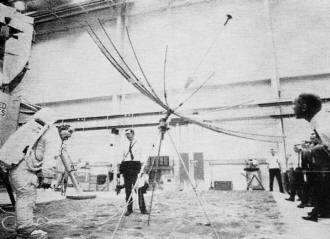

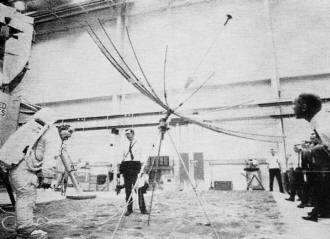

An Umbrella Antenna

The erectable 5-band antenna that will send microwave signals

from the Moon to Earth is going through simulated lunar setup.

The u.h.f. transmissions to and from the Moon once LM lands can be conducted

via a remarkable antenna. Called the "S-band erectable antenna," it is stored as

a cylinder only 10 inches in diameter and 39 inches long. After the landing, one

of the astronauts can remove the cylinder from the LM, set up its tripod, extend

the telescoping feed, attach a cable from LM, and "pop" the antenna much like an

umbrella so that it blossoms into a dish 10 feet in diameter. Total weight of the

entire antenna is 14 pounds.

For Apollo 11 the erectable antenna will serve as a contingency item, although

it is slated for prime use in future lunar landings.

The erectable antenna has 32-dB gain, about 12 dB more than the 26-inch steerable

dish on the LM which will handle S-band transmission and reception when the spacecraft

is in flight and after it lands. The erectable antenna focuses its energy so that

its transmissions will cover the entire portion of the Earth facing the Moon at

any given time.

Stretched between the antenna's ribs, which are jointed with watch-spring metal

so they can be folded, is an ultra-fine gold-plated wire woven into material resembling

ladies' mesh stockings. The total result is a very flexible assembly that springs

into a rigid structure when its opening mechanism is activated.

Live TV from the Moon

The most spectacular transmissions emanating from the lunar surface will be live

TV beamed to an international audience by a 7-pound camera built by Westinghouse.

The small camera will provide spectacular views of the astronauts as they move about

on the lunar-scape to gather rock and soil samples and to set up scientific instruments.

The pictures will be received on Earth, scan-converted, and released to the commercial

networks for broadcast to home TV sets. Scan conversion of the signals is needed

because the TV camera, to conserve power and communications bandwidth, operates

on standards markedly different from commercial TV.

Instead of the 525-line TV pictures broadcast at 30 frames-per-second of conventional

TV, the camera transmits 320-line TV pictures at 10 frames-per-second. This enables

it to operate on a 500-kHz bandwidth as contrasted to 4.5 MHz for commercial TV.

The camera also operates in a second mode, sending high-resolution "still" pictures

of 1280 lines at one frame each 1.6 seconds.

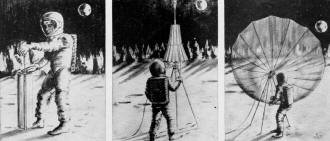

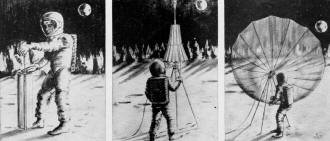

The three steps required to set up the erectable 5-band antenna.

At left, the feed is being extended; at center the tripod has been set up and cover

removed; at right, fully deployed antenna.

In either case, the Earth-based scan converters, built by RCA, through a virtually

instantaneous recording-playback process, transform the Apollo camera pictures to

commercial standards so they can be displayed on conventional sets. Each converter

employs a TV monitor, a vidicon camera, a video recorder similar to the "instant

replay" devices used in sports telecasts, and pulse and timing units.

The lunar-surface camera is one of two that will be used for Apollo 11. A larger

Westinghouse color camera identical to the one carried on Apollo 10 will fly in

the CSM to broadcast TV during the trips to and from the Moon and perhaps while

the CSM maintains its vigil in lunar orbit after the landing and during the exploration.

Both cameras already have made their space debuts. The amazing detail they provided

of the astronauts at work, the Earth and Moon, and the spaceships in orbit spellbound

TV viewers everywhere.

As spectacular as it will be, however, the TV will be only a small part of the

total information that will be showered on Earth by the LM communications systems

during the lunar visit. Vital astronaut physiological functions such as heart rate

and temperature, telemetry on the spacecraft systems, voice conversations, and status

of EVA spacesuit conditions (such as temperatures and oxygen supply), as well as

the TV, will all ride to Earth simultaneously on the S-band carrier, producing thousands

of bits of data each second.

Ranging Data & Navigation

When the astronauts return to the LM and fire its ascent engine to climb back

into lunar orbit and rejoin the CSM there, the LM communications system will take

on an additional chore: receiving and retransmitting ranging signals from Earth.

The range interrogations, like command and voice signals, will be received on 2101.8

MHz. They will then be turned around and transmitted on 2282.5 MHz, the carrier

for all LM S-band transmissions.

An opened extra vehicular communications system radio similar

to the ones used by our astronauts is being tested here.

As LM ascends, its v.h.f. set will be in action linking it with the CSM it is

seeking. In addition to handling voice and low-bit-rate data, the v.h.f. radio will

allow the CSM to compute distance between it and the LM. It does this by transmitting

a series of tones, which are received and retransmitted by the LM. By measuring

the time between transmission of the tones and receipt of the returns, the CSM-to-LM

range can be calculated. The voice and the ranging functions can be performed simultaneously.

This is the first v.h.f. system ever created with this capability.

The primary source of range data between the LM and CSM when they are separated

in space, however, will come from a silent communicator - the LM rendezvous radar

built by RCA. The X-band instrument, the first gimballing radar ever flown in space,

will track a transponder in the CSM to produce information on velocity and direction

of the CSM relative to the LM, as well as distance between the two.

The radar and v.h.f. communications thus give Apollo 11 dual sources of information

that will enable the LM to fly its way back to the CSM. The critical nature of the

rendezvous and docking is underscored by the fact that LM is solely a spaceship

that cannot re-enter Earth's atmosphere without being destroyed by the stresses

of gravity and atmospheric friction. LM must rejoin the CSM after the lunar landing

so that Armstrong and Aldrin can return safely to Earth with Collins.

The creation of the Apollo LM communications system has dipped deeply into the

reservoir of America's electronic technology and experience. Although the systems

design management task was performed by RCA's Defense Communications Systems Division

in Camden, N.J., LM communications equipment builders read like an electronics "Who's

Who:" Collins Radio for the S-band signal processor, Motorola for the S-band transceivers,

Raytheon for the S-band power amplifier; and Dalmo-Victor for the S-band steerable

antenna. RCA at Camden built the v.h.f. sets as well as the extra-vehicular radios,

and its sister unit in Moorestown, N.J. developed the unique erectable antenna.

Except for the antennas, which serve as back up to one another, each item of

LM communications equipment is redundant, providing an alternate means of accomplishing

its task if the prime unit fails. Solid-state design and construction, except for

an amplitron tube in the S-band power amplifier, are employed throughout the system.

The CSM's counterpart communications system, although the design of some equipment

items are different, is a functional duplicate of the LM S-band and v.h.f. radio.

With the LM system, it forms one-half of the Apollo communications complex.

The second half is the Earth-based Manned Space Flight Network (MSFN) managed

by NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center. Strung around the globe are S-band receiving

sites whose 30-foot and 85-foot antennas will peer spaceward throughout the Apollo

11 mission to receive the CSM and LM transmissions from the air, and to send voice

and data to the spaceships. The stations are referred to as unified S-band sites

since one antenna and one system handles all the communications functions; TV, voice,

telemetry, and tracking.

Besides the sites based on land across the United States and in several foreign

countries, Apollo receiving stations also ply the seas and the air in specially

designed ships and converted jet aircraft. The ships and aircraft fill the gaps

and provide coverage where no land stations can be situated.

Tying all these stations together is the NASCOM network, a system of radio, satellite,

and land-line communications that has the complex task of keeping the network linked

together so that the Apollo voice, data, and TV will flow uninterrupted to the NASA

Manned Spacecraft Center in Houston.

It is paradoxical that despite the capability of the Apollo spacecraft communications

systems, and the huge complex on the ground, critical phases of the flight can occur

when communications between the spacecraft and Earth are impossible. For example,

the engine firing that will drive the CSM out of lunar orbit so the astronauts can

return home will take place when the spacecraft is on the backside of the Moon and

communications signals are blocked from Earth. Thus, as was the case in the Apollo

8 and 10 lunar missions, the world will have to wait until the spaceship swings

around the lunar horizon to learn the success of the maneuver.

However, the first step onto the Moon by an American will be in clear sight of

the Earth, electronically. When the moment comes, it will be remembered as long

as civilization survives; the achievement alone is enough to assure that. Yet, the

impact and accomplishment of the manned lunar landing surely will be felt more sharply

on Earth because of the electronic beams that will span the void of space to bond

Apollo 11 and astronauts Armstrong, Aldrin, and Collins to their native planet.

Posted August 8

(updated from original post on

8/9/2017)

|

When men first walk on the Moon's surface, they

will be able to communicate by v.h.f. radio with each other and with the command

module orbiting overhead. They will also be directly in touch with Earth by microwave

radio and will be able to send back live television pictures over the vast translunar

distance.

When men first walk on the Moon's surface, they

will be able to communicate by v.h.f. radio with each other and with the command

module orbiting overhead. They will also be directly in touch with Earth by microwave

radio and will be able to send back live television pictures over the vast translunar

distance.