|

April 6, 1964 Electronics

[Table of Contents] [Table of Contents]

Wax nostalgic about and learn from the history of early electronics.

See articles from Electronics,

published 1930 - 1988. All copyrights hereby acknowledged.

|

I'm having a hard time writing

this with my

eyes rolled back in my head. The last time I experienced this level of overwhelmedness

was probably the third or fourth week of my feedback and control class at the

University of Vermont (UVM). Even

though electricity and magnetism shares many complimentary and parallel concepts,

for some reason thinking in terms of magnetics when describing amplifiers, mixers,

modulators, etc., has always caused brain freeze. Maybe it has to do with an ingrained

bias due to my earliest dealings with circuits being from a technician background

before earning an engineering degree. The equations of electric fields and magnetic

fields are very similar so that helps lower the barrier a bit. An engineer I worked

with once had the uncanny ability to comprehend time domain waveforms in the frequency

domain, and vice versa, when viewing an o-scope or spectrum analyzer display. Sure,

simple things like sine waves or square waves can be recognized by most people who

have been in the field for a couple years, but this guy's ability went way beyond

that.

Magnetoresistance: Better than Hall-Effect Multipliers

The author

S. F. Sun joined the Institute of High-Frequency Technology, Technical University

of Stuttgart, Germany in 1961 as a Research Fellow sponsored by the German research

foundation, Deutsche Forshungsmeinschaft. Since 1954, he has been engaged in the

application of solid-state devices at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology

and in industry. He is currently engaged in research on the microwave application

of semiconductors. Dr. Sun received his B.Sc. degree in electrical engineering from

the University of Chekiang, Hangchow, China, in 1946; the M.Sc. degree in engineering

from the University of London, England, in 1953, and the Dr. Sc. degree in technology

from the Swiss Federal Institute, in 1955.

A new circuit makes this multiplier practical in many applications. It is more

efficient than Hall-effect devices currently used in amplifiers and oscillators

By S.F. Sun

Institut fur Hochstfrequenztechnik, Stuttgart, Germany

Physicists have known for years that the magnetoresistive effect in semiconductors

(the resistance of a material changes in a magnetic field) was theoretically more

efficient for high (3000) gauss fields than the Hall effect where a semiconductor

carrying a current generates a voltage at right angles to the current. The magnetoresistive

effect could be especially useful in devices like a multiplier (two input voltages

are multiplied to produce the output) but has been impractical because the magnetoresistive

element always needed an extra-biasing magnetic field to improve its non-linear

characteristics. This extra field posed additional problems. If the field was weak,

it did not make the element sensitive enough or linear enough for large signal applications.

To make a strong field, an engineer had to design a complex and impractical circuit.

The extra-biasing field is no longer needed, however, if a specially designed

push-pull magnetoresistive circuit is used. This new circuit basically is a three-dimensional

multiplier that can replace any Hall-effect device. It is more sensitive and more

efficient than the widely used device. In addition, the magnetoresistive multiplier

is easier to adjust than a Hall-effect device and can operate at room temperature.

Particularly in Europe, Hall voltage generators have been put to work in industry

because they are simple, economical and reliable. The new magnetoresistive multiplier

may well replace Hall devices in such applications as amplifiers, mixers, modulators

and d-c transformers.

Theory

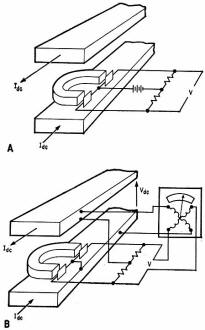

3-D multiplier with input currents representing three parameters

and output voltage giving their product (A). Dynamic characteristic curves of bridge

(B). Practical circuits relationship (C) of output voltages A and B and amplifier

current I6, can be used to carry out a large number of mathematical operations.

The increase in semiconductor resistance influenced by a weak magnetic field

may be considered as following the square law, in relation to flux density. In terms

of flux density B, the resistance R may be expressed as:

R = R0 + mB2

where R0 is the initial resistance at zero magnetic field and m in

the equation is a proportionality constant.

A magnetoresistive unit consists of a semiconductor placed in the air gap of

a magnetic core which has two excitation windings. If two semiconductors with identical

properties are used, and are arranged in a bridge circuit (similar to a push-pull

amplifier) the external resistance (Rex) is much larger than that of

the semiconductors. With one unit subjected to the influence of the sum of two variable

magnetic fields, (B1 + B2), and the other subjected to their

difference (B1 - B2), the resistance of the specimens R1

and R2 becomes:

R1 = R0 + m (B1 + B2)2

and

R2 = R0 + m (B1 + B2)2

respectively. Under conditions that the magnetic cores are well below saturation

and the core reluctance is negligibly small in comparison with that in the air gap,

inductions B1 and B2 may be considered as proportional to

the excitation currents I1 and I2.

Computing with a Magnetoresistive Multiplier

I6 = Kx = (KA/KB) (I1I2I3

/I4I5)

This relationship can be used to carry out a large number of

mathematical operations (see table).

By passing a current of equal magnitude (I3) through each unit, the

voltage difference, V, between the terminals of R1 and R2

will be

V = I3 (R1 - R2) = 4m

B1 B2 I3

or

V = K I1 I2 I3

where K is a constant which includes the factor 4m and also takes care of the

proportionality between the inducted and the exciting currents. The result is a

three-dimensional electronic multiplier whose input currents represent three parameters

and whose output voltage gives their product.

The 3-D multiplier may be reduced to a two-dimensional multiplier by keeping

one of the parameters B1, B2 or I3 constant. This

parameter will then be used to adjust the sensitivity of the device or to improve

the linearity of the composite characteristics. Some examples of practical circuits

follow.

Analog Computing Element

Since the output voltage of the multiplier is proportional to the product of

three currents, the output voltages of two multipliers, A and B, can be written

as

VA = KA I1 I2

I3, VB = KB I4 I5 I6

respectively. If the outputs of multipliers A and B are connected to a difference

amplifier, and VA and VB will be compared and, as a result,

the amplifier will supply to unit B an output current corresponding to I. This current

will become stable when VA is equal to VB; it gives the equations:

I6 = (KA/KB) (I1I2I3

/I4I5).

Polyphase Wattmeter

In electrical power system, the multiplier is modified by a permanent magnet

inserted in the core of the magnetoresistive unit. This allows one of the variable

magnetic fields to be kept constant. The voltage difference, V, will be reduced

to

V = (4mB1) B2I3 = K I2I3

Polyphase wattmeters, (A) and (C), are modified, (B) and (D),

to measure reactive power or apparent power.

Magnetoresistive elements replace nonlinear elements in mixer

circuits (A) and modulator circuits (B) because they can operate in the multiplication

model.

Amplifier in (A) is modified with feedback winding in (B) for

a d-c amplifier. If the feedback is equal to or larger than unity and a capacitor

is connected between the feedback windings, the oscillator shown in (C) is produced.

Two capacitors in tank circuit give oscillator (D).

If the excitation current I2 of the variable field is made proportional

to the instantaneous phase current, i, of an electrical power network, while the

current I3 through the semiconductor is proportional to the instantaneous

phase voltage, so that

I2 = ki i = ki Im

sim (ωt + θ)

and

I3 = ke = ke Em

sim ωt

the output voltage of the multiplier will become V = KI2I3

V = K I1I2

= - 1/2 Kki ke Im Em

cos (2 ωt + θ) + 1/2 Kki ke Im Em

cos θ

which consists of an alternating-current and a direct-current component, the

latter being in proportion to the power of the network. It is possible to construct

a polyphase wattmeter with a single indication to show the total power consumed

in a multiphase system. Take a three-phase network as example; the circuit arrangements

are shown with those parts enclosed by the dotted lines as units of a single-phase

wattmeter. Since the current in the semiconductor is drawn from the source through

a voltage transformer, the output terminals of the units can be joined in series

so that the output voltage will be added together and the sum can be indicated by

a d-c voltmeter. Modifying the circuit produces polyphase power meters able to measure

reactive power or apparent power.

Amplifiers and Oscillators

There are many ways to construct amplifiers and oscillators. One of them is to

make two of the parameters of the three-dimensional multiplier mutually dependent,

for example B2 = k I3 so that the voltage different may be

rewritten as

V = 4mkB1I32 = KB1I32

where the k's are a proportional constant. An amplifier circuit has the field

winding of B2 in series with the semiconductor and the input is applied

to the field winding of B1 which may have many turns. The amplitude of

the output voltage will be controlled by current I3 and is proportional

to its square.

An amplifier is shown with a feedback winding that may produce an induction B,

additive (or subtractive) to B1. If the mmf (magnetomotive force) required

by the magnetic path in the core is negligible, the value of B will be dependent

on the air-gap length g, the permeability in the gap μa the resistance

of the feedback winding r and the number of turns of the feedback winding N. The

voltage difference becomes

V = K I32 (β1 VNμa/2gr

or

V = K I32 β1 / (1 - KNμa

I32/2gr)

and the output voltage V is increased by the factor of

α = 1/(1 - KNμa I32/2gr)

This kind of amplifier with feedback arrangement is suitable only for d-c signals.

In the last voltage difference equation, if the feedback term

β = KNμa I32/2gr

is made equal to or larger than unity, the circuit becomes unstable and an oscillator

can be obtained by simply connecting a capacitor between the two feedback windings

and omitting the field winding of B1. Frequency f will be determined

by

f = 1/2π √(LC)

with L the total inductance of the windings and C the capacitance. Another example

for an oscillator circuit is given in (D) where two capacitors complete the tank

circuit.

Mixer, Modulator and Demodulator

Magnetoresistive elements and three experimental multipliers

using them. Two types of magnetoresistive semiconductor elements are shown, one

imbedded between two square ferrite plates and the other deposited up on a substrate

the size of filament wire.

Since all these devices are based upon a process by which the output frequency

differs from the input signal, yet is controlled by it, the nonlinear elements,

used to achieve this purpose, can be replaced by magnetostrictive elements capable

of multiplication operation. Circuit (A) illustrates a three-dimensional multiplier

as a mixer. Signals of different frequencies f1 and f2 are

fed to any two inputs of the three parameters, while the last one supplied with

d-c can be used as a means of regulating the amplitude of the output voltage consisting

of the components of (f1 + f2) and (f1 - f2).

Eventually the last parameter can also be used as the input of a third signal of

frequency f3 to mix three frequencies.

The principles of modulator and demodulator are similar and explained by an example

of a demodulator. The semiconductors bridge circuit (B) receives a modulated signal

from input terminals while one of the magnetic fields is tuned to the carrier frequency

by means of a resonant circuit and a local oscillator. The third multiplier parameter

is the amplitude control element. If the input modulated signal is

e1 = E1 (1 + M cos ωMt)

cos ωct

and the local oscillator supplies to the field winding of a signal of

e2 = E2 cos ωct

the output voltage of the three dimensional multiplier is

V = e1 e2 = E1 E2

(1 + M cos ωMt) cos2 ωct

= 1/2 E1 E2 [1 + M cos ωMt

+ cos (2 ωc + ωM) t + cos (2 ωc

- ωM) t]

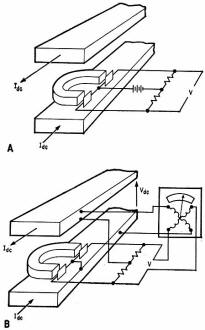

Heavy d-c measurements are possible with circuit in (A) where

heavy doc flowing through bus-bars is measured with d-c or a-c voltmeters. Arrangement

in (B) requires no extra supply for the bridge circuit and provides an accurate

measurement unaffected by doc voltage fluctuations.

The modulating term (M cos ωMt) can be filtered out by conventional

techniques.

D-C Current Transformers

This device is suggested for measurement of very heavy direct current. Using

the magnetic field of an U-shaped permanent-magnet as the constant bias field the

magnetoresistive elements are placed on the pole faces and the whole unit is situated

between the d-c bus-bars. With the bridge circuit drawing current from a d-c or

a-c supply, the heavy d-c through the bus-bars will excite a magnetic field on the

specimens and be measured with a d-c or a-c voltmeter.

If the d-c voltage of the bus-bar supplies current to the bridge, the voltage

at the output will be proportional to the power through the bus-bar. However, by

means of a quotient-measuring instrument having one pair of its terminals connected

to the output of the multiplier, and the other pair connected across the bus-bar

voltages the current in the bus-bar will be indicated by the deflection of the instrument ψ,

which is

ψ = K Vdc Idc/Vac

= K Idc

This arrangement has the advantage that no extra supply for the bridge circuit

is required. Also, the correct value of the direct current is always shown by the

instrument without being affected by doc voltage fluctuations.

Experimental Result

The perfection of a three-dimensional multiplier depends mainly on its linearity

and sensitivity. With InSB (Indium antimonide) of proper doping as the active element,

it is possible to make magnetoresistive specimens with resistance equal to 100 ohms

at zero flux density, and about seven times that amount at a flux density of 10

kilo gauss. The specimen is reproducible and almost temperature independent within

the range of ordinary working temperatures. Characteristic curves of two such magnetoresistive

specimens are shown to have identical form when the magnetic field is less than

four kilogauss. The three-dimensional multiplier constructed with these elements

will have a family of curves which are very linear when B1 and B2

are less than four kilo gauss but do not go exactly through the origin. This discrepancy

can, however, be eliminated by introducing a potentiometer of low resistance between

the magnetoresistive elements. If the external resistances Rex are connected together

through a potentiometer, and the field circuit of the individual magnetoresistive

unit is provided with tunable choke coils, the linearity and symmetry of the characteristic

curves can be adjusted. Further adjustment is possible by varying the length of

air gap in the magnetic core.

Indium antimonide used in two active elements gives identical

curves when the magnetic field under four-kilogauss (A). A 3-D multiplier using

these elements gives the family of curves in (B). The curves are linear when variable

magnetic fields are less than four-kilogauss.

Using a control current I3 = 10 ma and at B1 = B2

= 2 kilogauss, the experimental multiplier has an output voltage of 1.2 volts. Since

the magnetic fields are low, the magnetic circuit can he constructed with small

ferrite cores of very narrow air gap, and the indium antimonide which is in the

form of a thin film may be deposited directly on the pole face. The multiplier unit

can thus be made compact, shockproof and rugged.

Other advantages include lifetime of all parts in the multiplier is practically

unlimited; the multiplier is also suitable for high frequency operation up to the

megacycle range; and, the output of the multiplier can be used in regulation or

telemetering applications.

The efficiency of the magneto resistive device is always better than that of

a Hall effect device when the magnetic field is sufficiently large. To obtain higher

efficiency, the magnetic core should be composed of a material other than a ferrite,

so that larger flux densities can be applied to the specimen without approaching

core saturation.

The author thanks Professor H. Welker and H. Weiss, Siemens-Schuckertwerke, Erlangen,

Germany, for supplying the semiconducting materials used in construction of the

above units.

|