|

September 19, 1966 Electronics

[Table of Contents] [Table of Contents]

Wax nostalgic about and learn from the history of early electronics.

See articles from Electronics,

published 1930 - 1988. All copyrights hereby acknowledged.

|

The more things change, the

more things remain the same. To wit: "When this circuit learns your job, what

are you going to do?" asks a poster now appearing widely in subways and buses.

That statement appeared in a 1966 issue of Electronics magazine that was

reporting on the state of the art in computer-aided design (CAD) of circuits. People

are saying the same thing today about Artificial Intelligence (AI). The fact is

that AI has been around for as long as there have been machines capable of

solving problems, detecting errors, and making suggestions for improvement. If

you think maybe high capability CAD is relatively new on the scene, or that

early attempts were extremely primitive, disabuse yourself of that notion by

reading through the article. Inputs were via punch cards and tape, but the

mathematical modeling and matrix functions would make most modern day engineers'

eyes roll back in his head. Transistor (BJT and FET) models were composed of 32

parameters, filter models included amplitude, phase, and group delay for

multiple topologies, passive components included parasitic values, etc.

Designers wanted more capability, of course, but many top-tier companies used

in-house or commercially available programs - which would not have been the case

if it was not financially beneficial. For context,

SPICE came online in 1975,

nearly a decade after this article. My first circuit simulator use was

with

Micro-Cap, while working

on my BSEE at the University of Vermont in the late 1980s; it ran on an

ATT PC 6300 with an

i8085 microprocessor and, 10 MByte hard drive, and a 5-1/4" floppy drive.

The Man-Machine Merger

The circuit designer and the computer are headed for a new relationship, say

the experts, with the computer as the bright, young, junior partner and the designer

as the undisputed boss.

By Donald Christiansen, Senior Associate Editor

"When this circuit learns your job, what are you going to do?" asks a poster

now appearing widely in subways and buses. Intended to alert the public to the need

for job retraining to replace obsolete skills, the rhetorical question can strike

momentary terror in the heart of the circuit designer, who suddenly wonders if he

is designing himself out of a job.

Unmistakably, the electronics industry is on the threshold of a new era in circuit

design. Directly ahead is the period in which circuits - specifically, computer

circuits - designed by an engineer may invade the decision-making area that was

once the engineer's exclusive province. The circuits he designs may in turn design

new circuits.

Faced with this probability, the old-time electronicker, operating solely by

intuition and experimentation, has cause for fear, but only if he turns his back

on the revolution in progress and ignores the fact that the computer is already

working on circuit design. The machine is assisting the engineer by

• Performing repetitive calculations.

• Evaluating the effects of changes in circuit parameters caused by component

tolerances, drift, etc.

• Studying the feasibility and cost of circuit optimization.

• Simulating component failure.

• Developing optimum physical device layouts and optimum circuit interconnection

paths.

A computer can do a little or a lot; it can be a modest aid or a tremendous help.

It can be used at few or many stages of the design process. To decide on the best

use of so versatile a tool, computer application consultants at the International

Business Machines Corp. suggest that the design process itself be examined first.

After that, one can judge which stages of the process should be computerized. The

designation of a program depends on this judgment. Unfortunately, confusion is rampant

in definitions that relate to computer-aided design. Among terms used frequently

and often indiscriminately are these: design synthesis, design automation and computer-aided

design.

Design synthesis may be thought of as the creation of a set of specifications

describing a circuit. Design automation, on the other hand, would include detailed

specifications and machine instructions required to fabricate the circuit. And computer-aided

design (CAD) indicates the use of a computer at one or more stages of the design

process.

The circuit designer and the computer are headed for a new

relationship, say the experts, with the computer as the bright, young, junior

partner and the designer as the undisputed boss.

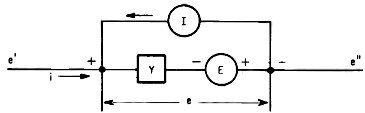

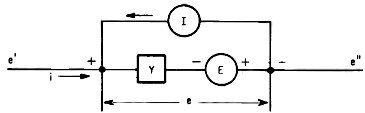

Basic branch for which an ECAP data card is prepared. E and I

are voltage and current sources, respectively, e and are branch voltage and

current, is the conductance of the passive element, and e' and e" are node to

datum voltages.

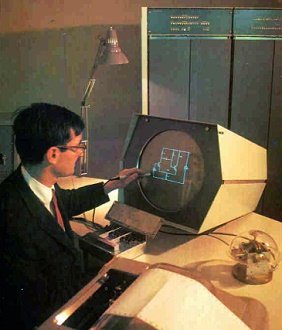

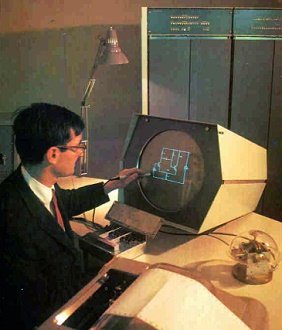

CAD expert Jacob Katzenelson communicates with Project MAC's

time-shared computer in an on-line demonstration using the MIT Electronic

Systems Laboratory console. Using light pen and typewriter he draws an

emitter-coupled multivibrator and assigns component values by typing or

sketching characteristics on the display console. Following computer analysis of

the circuit, waveforms can be viewed on the console, evaluated, and the circuit

returned to the screen for modification. The experiment is carried out by a CAD

program called AEDNET, written in MIT's AED-O language.

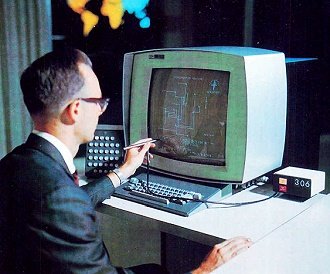

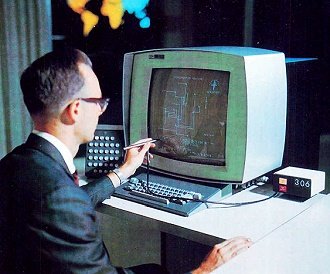

At this console in the IBM World Trade Center in New York, an

engineer from the Norden division of United Aircraft instructs an IBM 360

computer in a point-to-point wiring exercise, part of a project Norden has under

way to develop on-line methods of man-machine interactions for computer-aided

integrated circuit design. The experiment is conducted under an Air Force

contract.

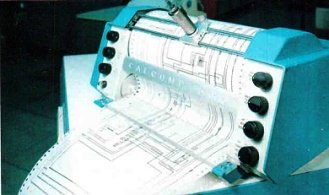

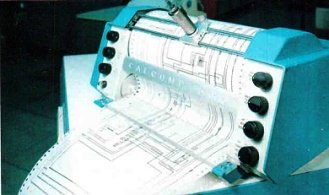

Final design of i-f amplifier at the right is drawn

automatically by the plotter.

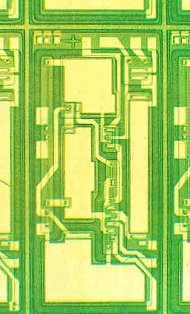

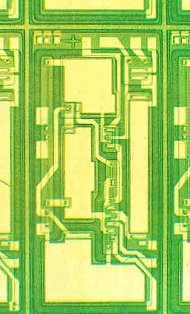

Integrated circuit intermediate-frequency amplifier designed

using the Norden-developed CAD program. Components are located and

interconnection paths developed with an assist from the computer.

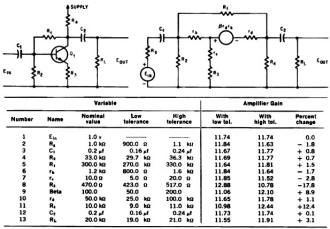

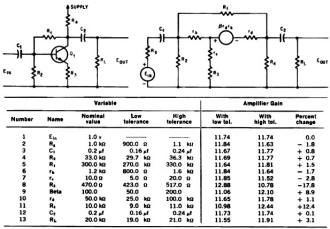

To carry out a sensitivity study of the common emitter

amplifier shown here, using the Arinc program, an equivalent circuit, top right,

is first developed. Then a description of each element of the equivalent circuit

(first five columns in table) is fed to a computer, along with the loop

equations and a request for a sensitivity analysis. The computer then provides

the results tabulated in the final three columns.

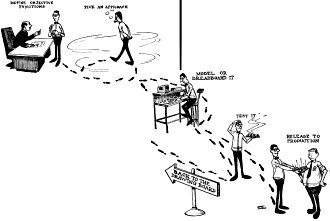

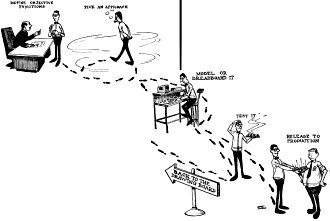

The Design Process

The designer usually goes through some sequence like this: statement of the problem

(or goals), choice of attack, paper design, breadboarding or modeling, optimizing

and checking effects of limit devices.

At the optimizing stage he diddles potentiometers and otherwise changes parameter

values, then checks circuit performance. The process is cut and try. Since his equipment

must operate with components that have some production spread, he then searches

for limit devices (transistors with high and low-limit beta, for example) plugs

them into the breadboard and notes the output. If it is not within spec he'll go

back, change some other component or parameter value, and check the result once

again. At some point short of perfection he'll freeze the design, knowing full well

that he'd better, or the equipment may become obsolete even before the prototype

is built.

Super Slide Rule Super Slide Rule

Assigning the repetitive cut-and-try tasks to a computer is the opening wedge

to completely automated design engineering. IBM calls this use of a computer the

"big slide rule" technique. While helpful, it is limited both in sophistication

and payoff.

If a computer can simulate a circuit, it can easily perform a given calculation

on demand. It is when the computer is called upon to employ its decision-making

powers that it plays its most significant role. Then, it can be used to relieve

the designer of many intermediate decisions ("Do we have enough gain in this stage,

or should we go back and change a resistor?"). Such an approach represents the beginning

use of the computer in design synthesis with the computer as a junior partner in

the man-computer merger.

Design Automation: An Example

Since the goal of the design process is to build equipment, the ultimate use

of the computer would be its control of the fabrication process for the equipment

it has "designed." When design engineering and manufacturing are linked by computer,

the process is termed design automation. Carried to its extreme, the technique would

mean that equipment could be manufactured directly from the customer's order with

little manual engineering. At that point, the computer will be in the main stream

of the design function; preparing the engineering paperwork - detailed configurations,

machine tool instructions and manufacturing control data - by which the equipment

is manufactured.

An example of how close design automation is to reality - at least in one area

- is the work done by the Norden division of United Aircraft Corp. under an Air

Force contract. Using the same basic circuit definition that was used in analyzing

the circuit, Norden developed programs that - through a series of man-machine interactions

- convert the circuit to a practical integrated circuit format, occupying a minimum

of area, with an optimized interconnection pattern. The intermediate-frequency amplifier

on page 118 was designed this way.

I. Among the Techniques, Dilemmas Galore

The computer is a rigid machine, refusing categorically to accept information

it cannot comprehend. Communicating with it poses a barrier to the circuit designer

because, the experts say, designers know little about programing and programers

know less about circuit design.

"What shall we tell the computer a circuit is?" is the basic question. Once a

model of the circuit has been developed that the computer can assimilate, it is

relatively simple to feed the machine a list of trial inputs, parameter values and

constraints. In effect, the computer is told: "Here's what we want in, here's what

we want out, and here's a trial design - let's see what happens."

Model Behavior

The accuracy of the circuit model fed to the computer determines how valid the

computer analysis is. A bad model yields a doubtful result.

Some circuit elements such as resistors are better behaved than others - and

can quite readily be represented to the computer. But active devices are tough to

model because they're not linear and react to temperature and frequency in a way

that is not easily formulated.

Research on what constitutes good models has led Cyrus Harbourt, a professor

at the University of Texas, to zero in on the narrower, but extremely salient question:

"What shall we tell the computer a transistor is?"

Harbourt says a good device model should successfully predict actual device performance;

contain only parameters which can be determined from practical measurements made

on real-life devices; and finally, it must be capable of being understood by the

computer. Harbourt says a good device model should successfully predict actual device performance;

contain only parameters which can be determined from practical measurements made

on real-life devices; and finally, it must be capable of being understood by the

computer.

A device model can be simple or complex. Complexity permits a more accurate representation

of the device over a wide range of circuit conditions. But the use of an overly

complex model for the task at hand is time-wasting. Conversely, a simple model is

efficient when assigned an appropriate task, but useless when overtaxed.

Perhaps the most complex transistor model is the one for NET-1, one of the two

widely used general-purpose computer programs. A transistor type is defined for

NET-1 by 36 parameters, which can be pre-stored on a library tape, or developed

for a new transistor.

In contrast, the other major electronic circuit analysis program, ECAP, uses

a do-it-yourself device model. ECAP provides resistors, capacitors, inductors, dependent

current sources, and a generalized ideal switch. The chief asset of the switching

function is that the value of parameters can be altered when selected currents reach

predetermined values.

Most designers say ECAP is superior when flexibility is sought, but they give

the nod to NET-1 for accuracy. Harbourt notes that with NET-1 a complex model must

be used even when dealing with problems as simple as a saturating logic circuit.

Users of NET-1 express dissatisfaction with the library of device models available

to them. Time, effort, and a free interchange among users may resolve the difficulty.

Little work has been done on models for the more exotic solid state devices.

Even field effect transistor models are hard to come by. Moreover, some phenomena

encountered in devices are difficult to model - minority carrier storage time is

an example. One of the few companies developing models for offbeat semiconductor

devices is Design Automation, Lexington, Mass.

The designer is still a long way away from the day when he'll push buttons that

feed circuit performance requirements into a computer and get a finished circuit

- integrated or otherwise. Today he is more likely to make his inputs in the form

of cards or tape bearing data that defines portions of the circuit, operating constraints,

and input signal conditions. Outputs for the most part are printed out.

Toward the Ideal: NET-1 and ECAP

The experts guess that there are anywhere from 200 to 2,000 programs for aiding

circuit design. Admittedly, the bulk of them are limited in scope and documentation.

Programs proliferate because it's often quicker to develop a new program than to

locate, decipher and debug someone else's.

Like the ideal secretary, a computer program must be versatile, efficient, accurate,

and above all, available. To gain wide acceptance, a program should handle steady

state (a-c and d-c) analysis as well as transient analysis. Franklin Kuo, network

analysis expert for Bell Telephone Laboratories, Murray Hill, N.J., thinks the perfect

program would have a simple input language, handle a wide range of models of physical

devices, and provide a nonlinear analysis capability. Kuo says that if automatic

parameter modifications were added - it could replace breadboarding - a design engineer

couldn't ask for anything more.

The two programs which come closest to meeting the ideal requirements are NET-1

and ECAP. NET-1 was developed on the Maniac II computer under the auspices of the

Atomic Energy Commission at the Los Alamos Scientific Laboratory of the University

of California, Los Alamos, N. M. Since its completion in 1962, the program has been

translated into versions for the IBM 7040, 7044, 7090 and 7094 computers, and is

used at over 60 commercial, government and university installations here and abroad.

One of the chief virtues of NET-1 is that it's easy to use. Specifically, the

user need not know how to solve simultaneous nonlinear differential equations, nor

manipulate matrix algebra, nor cope with numerical instability. He doesn't even

have to know simple programing techniques and, when analyzing a circuit, needn't

have the slightest idea how the circuit works.

If instructed properly, the computer will deliver an accurate circuit analysis

- one which may provide some insight into hazy circuit operation. NET-1 can simulate

fixed value resistors, capacitors, inductors and mutual inductive couplings. Additionally,

it can handle both junction transistors and diodes, fixed-value voltage sources

and several classes of time-dependent voltage sources - including trapezoidal, sinusoidal,

exponential and tabular waveshapes.

The transistor model for NET-1 requires specification of 36 parameters; the diode

model, 13.

ECAP, the other major general-purpose program, stemmed from the joint efforts

of IBM and the Norden division of United Aircraft. ECAP is written in Fortran for

the 1620, 7090 and 7094.

Using ECAP, the designer develops an equivalent circuit based on the circuit

he plans to study. In it, he is free to use any representation of a transistor or

diode that he chooses, providing it is modeled with conventional circuit elements.

In ECAP, the matrix approach is fundamental and information on basic network

branches are key entries to the computer. Each branch comprises three network elements,

pictured on the next page - a passive element (resistor, capacitor or inductor)

a voltage source and a current source. Branch terminations are called nodes.

Cards, representing the branches of the equivalent circuit, are punched. Each

branch card contains data that tells where the nodes are connected, identifies assumed

direction of current flow, and provides the value of voltage, current and passive

element. The input to each card is user-oriented; no translational language is needed.

ECAP can perform d-c, a-c and transient analysis and has options for sensitivity,

standard deviation and worst-case analysis.

Arinc Program

The Arinc Research Corp. at Santa Ana, Calif., has a general-purpose program

that can be used without knowledge of either Fortran or machine language. A circuit

to be analyzed is described by a linear equivalent circuit for which n simultaneous

equations in n unknowns are written. A source deck of punched cards contains the

circuit equations in standard matrix notation as well as equations describing the

desired output solutions.

Parameter data for the Arinc program goes on a separate deck of punched cards.

Each card represents one circuit element, and contains such data as nominal value,

tolerance limits, temperature drift limits, production distribution characteristics

and, if appropriate, alternate values.

The engineer feeds the two card decks to the computer, then specifies the analysis

options. These include one-at-a-time parameter variation and sensitivity tests,

worst-case solutions with all components at drift limits, a Monte Carlo analysis

to determine the probable spread of circuit performance in large-volume production,

and solutions representing combinations of circuit values.

An Example

It may be profitable to follow the steps of the Arinc program on a very simple

common emitter amplifier. First, the designer converts the schematic to the equivalent

circuit shown. Then he writes a matrix of five simultaneous equations representing

the five circuit loops. Each of the elements of the equivalent circuit gets an input

variable number, V1, V2, V3, etc.

Each of the coefficients of the equations is punched on a separate card in terms

of input variable numbers.

Then cards are punched - one per input variable - that contain the nominal value,

tolerance limits, distribution shape, and so forth. For this example, data on the

card is listed in the first five columns of the table below the circuit schematics.

If an order goes into the computer for a sensitivity test, using the circuit and

input variable data that the designer has supplied, the machine will print out the

data listed in the last three columns of the table. It's evident that the culprits

are R3, R4, and the transistor beta; that is, if the values of R3, R4, and hFE are

permitted to reach their tolerance limits, large shifts occur in amplifier gain.

It should be obvious that the Arinc program cannot be listed among the most sophisticated,

since the user must still write the circuit equations. But in the future he'll merely

have to supply the equivalent circuit, says Robert Mammano, specialist in circuit

analysis for Arinc.

II. Practice: Some Successes, Some Failures

Among firms already applying computers in circuit design are the Autonetics division

of North American Aviation, Collins Radio, Hughes Aircraft, Friden Corp., RCA, and

Bell Telephone Laboratories.

Having worked on computer-aided design since 1959, Autonetics has produced several

home-grown programs. Mostly they are for digital circuitry, such as computer circuits

for Minuteman airborne computers. For two years Autonetics has used a program which

accepts point-to-point topology and prepares equations automatically [See "Circuit

analysis by computer," p. 120]. The division has also applied computer-aided design

to advanced radar systems using integrated circuits.

Simulating Failures

Autonetics also has a failure mode and failure effects analysis program. In the

program, destruction of one circuit element is simulated and overstress of other

components noted. At the same time, voltage readings at monitor points within the

circuit are recorded. With this data as a guide, the engineer can rapidly judge

which component has failed in an actual circuit, without removing individual components

for testing. The advantage is obvious, but a specific example is the Minuteman D37

computer; once a component - even a good one - is removed it cannot be replaced.

In one of Autonetics' programs, a computer will select the best device among

several. In effect, the computer is fed the characteristics of several transistors

along with the circuit requirements. The program picks the best transistor and reads

out the biasing voltages required.

The Collins Radio Co. uses ECAP for the design of linear circuits and some digital

circuits. Its designers find the program particularly useful for design of small-signal

amplifiers, d-c amplifiers, balanced modulators, phase detectors, active filters,

and power supplies. A major use of ECAP by Collins is in checking circuits for tolerance

to parameter shifts.

Worst-Case Studies

The Hughes Aircraft Co., Culver City, Calif., uses ECAP for worst case, transient

and frequency analysis. At Hughes' Research and Development division ECAP aids in

the design of linear circuits in airborne radar and communications packages such

as those for Early Bird and Syncom satellites. ECAP has been very useful in detecting

errors and in establishing tolerances, Hughes says.

ECAP helps the Friden Corp.'s military products section, San Leandro, Calif.,

in digital circuit design, primarily for circuit analysis and reliability studies,

and in optimizing topological layout. Its big advantages, Friden engineers say,

are in saving time, providing insight, and pointing out redundancy. So far, Friden

has not used ECAP in design synthesis.

NET-1 is at work for the Radio Corp. of America's Aerospace Systems division,

Burlington, Mass., along with home-built programs, selecting existing circuits to

perform a specified function, determining circuit response, optimizing circuit performance,

and studying circuit reliability.

The special programs used by this RCA division include a small-signal a-c program

based on nodal analysis, a nonlinear large-signal program using mesh techniques,

and a piecewise linear program.

Fairchild Semiconductor's active filter facility, Mountain View, Calif., uses

computers for filter design. Two Fairchild-developed programs - one for synthesis,

the other for analysis - are used. With the first, the customer's specifications

go directly into the computer. The computer then spells out the structure and element

values needed to realize the specifications (the output is a list of capacitors

and resistors). The second program accepts a circuit description and reads out the

filter characteristics to be expected.

For two years the Centralab division of Globe Union, Inc., Milwaukee, has used

ECAP in designing hybrid circuits. The circuits contain film-type passive components

deposited on a ceramic substrate, with active chips added. J.E. Brewer, Centralab's

manager of advanced design, notes that an advantage of the hybrid technique is that

all the resistive components are accessible and can be precisely trimmed. Among

other things, ECAP can spell out the required tolerances, resistor by resistor.

At Norden, some of the most advanced work in CAD is under way. "We pick and choose

among available programs," says Martin Goldberg, CAD specialist. "For a-c analysis

we're using ECAP; for transient analysis, NET-1, and for nonlinear work we're using

our own nonlinear extensions of ECAP."

Shortcomings

Most criticism of existing programs for computer-aided design focuses on their

limited flexibility or limited capacity. Frequently voiced complaints concern the

programs' limited ability to handle nonlinear circuits and restrictions on the size

of the circuit that can be studied. NET-1, for example, can handle 300 each of resistors,

capacitors and inductors, 63 fixed-voltage sources, 63 time-dependent sources and

200 nodes (based on 32,000-word memory). ECAP can handle 50 nodes, 200 branches,

200 dependent sources, and 200 switches in its 7094 version, but only 20 nodes and

50 branches for the 1620.

Dennis Walz, head of circuit and component design for Collins Radio's facilities

at Newport Beach and Santa Ana, complains that accounting for nonlinearities, in

diodes for example, is accomplished by ECAP only in "raw approximations."

The driving-point functions now available for linear circuits don't cover all

the points Collins would like to have, Walz says. ECAP, he adds, can't handle discontinuous

sine waves adequately. Collins is trying to modify the time-step routine so that

the program will handle a larger network, shorter time intervals, and more of them

- up to real filter synthesis program it is worth while in cases where large numbers

of filters must be designed to meet different specifications.

One program for filter design has been written by Szentirmai. The program is

complete in that it handles the approximation and synthesis problem. It can handle

low-, high-, and band-pass filters with prescribed zeros of transmission. There

are provisions for either equal-ripple or maximally flat-type pass-band behavior,

for arbitrary ratios of load-to-source impedances and for predistortion and incidental

dissipation. The second program synthesizes low- and band-pass filters with maximally

flat or equalripple-type delay in their pass band and monotonic or equal-ripple-type

loss in the stop bands.

The engineer is free to specify both the zeros of the loss peaks and the network

configuration desired. If his specifications include neither, the computer is free

to pick both configuration and zeros of transmission. The computer chooses a network

in which the inductance values are kept at a minimum. The network can be synthesized

from both ends.

Finally, the computer prints out the network configuration, its dual, the normalized

element values and the denormalized ones. Information such as amplitude and phase

response, as well as plots of these responses obtained from a microfilm printer,

are also provided by the computer.

Filter designs obtained using the computer are completed in minutes rather than

days and at a typical cost of $20 rather than $2,000 (not including initial programing

costs).

Network Topology

It is sometimes necessary to compute a network function in symbolic rather than

numerical form. Although symbolic determinants can be evaluated, the process is

slow and complicated. Topological formulas provide a solution.

The generation of trees (a way of representing a network by a set of open branch

elements that include all nodes of a given circuit) with the proper sign is the

main problem of topological analysis of networks. For this purpose, several procedures

have been designed for the computer. However, the use of topological formulas for

network analysis does not appear as efficient as other methods. This is primarily

due to the fact that the number of trees of a network with say 11 nodes and 21 branches

can be about 13,000.

Optimization

Network design is not always accomplished by simple substitution in formulas.

Trial-and-error processes are often used. The network designer starts with a set

of specifications, selects a network configuration and makes an initial guess about

the element values. He then measures or calculates the desired responses and compresses

them with specifications. If the measured responses differ widely from the specified

responses, the designer changes the values of the elements and compares again. The

process is repeated until the measured responses agree with the specified responses

within a preset tolerance.

A cut-and-try process can be made to converge quite rapidly using the method

of steepest descent. A steepest-descent Fortran program used for designing delay

networks has been described by Semmehnan.

To use the program, the network designer first selects the initial values for

the parameters xi. He must also provide the specified delays and the

frequency data points. The program successively changes the parameters so that the

squared error is minimized. The program provides for 128 match points and 64 parameter

values. It is capable of meeting requirements simultaneously in the time and frequency

domains. The designer is not restricted to equalripple approximations or infinite

Q requirements. He is free to impose requirements such as nonuniform dissipation

and ranges of available element values on the design.

References

1. T.R. Bashkow, "The A Matrix-New Network Description," IRE Trans. on Circuit

Theory. CT-4, No. 3, Sept. 1957, pages 117-119.

2. G. Szentirmai, "Theoretical Basis of a Digital Computer Program Package for

Filter Synthesis," Proc. of the First Aller. ton Conference on Circuit and System

Theory, No. 1963, University of Illinois.

3. Charles B. Tompkins, "Methods of Steep Descent," Modern Mathematics for the

Engineer (Edwin F. Beckenbach, ed.). Chapter 18, McGraw-Hill Book Co., New York,

1956.

4. C.I. Semmelman, "Experience with a Steepest Descent Computer Program for Designing

Delay Networks," IRE International—Convention Rec., Part 2. 1962, pages 206-210.

Bibliography

Franklin F. Kuo, "Network Analysis and Synthesis," Second Edition. John Wiley &

Sons, Inc., New York, 1966.

Franklin F. Kuo and James F. Kaiser, "System Analysis by Digital Computer." John

Wiley & Sons, Inc., New York, 1966. Franklin F. Kuo, "Network Analysis by Digital

Computer." Proc. of IEEE, June 1966, pages 820-829.

|