|

October 1959 Electronics Illustrated

Table of Contents Table of Contents

Wax nostalgic about and learn from the history

of early electronics. See articles from Electronics Illustrated, published May 1958

- November 1972. All copyrights hereby acknowledged.

|

In this 1959

Electronics Illustrated magazine article, C. M. Stanbury argues that the U.S.

is losing the Space Race not due to a lack of technology, but due to a critical

failure in propaganda and prestige warfare against the Soviet Union. While American

satellites use more reliable VHF for precise scientific data, their signals are

only received by a handful of specialized monitoring stations. In contrast, all

Russian spacecraft broadcast on shortwave frequencies around 20 mc, allowing thousands

of amateur radio enthusiasts worldwide to directly hear their satellites, a tangible

proof of communist achievement. The author, who personally received a verification

card from Moscow for tracking Sputnik I, contends this publicity strategy brilliantly

sways unaligned nations in Africa and Asia. He concludes the U.S. must immediately

add simple shortwave transmitters to its payloads to provide the world with audible,

undeniable evidence of American prowess, a small cost for immense prestige gains.

The Race to Space - Are We Losing Prestige?

By C. M. Stanbury, II By C. M. Stanbury, II

For practical purposes, the real bread-and-butter conquest of space probably

won't begin for another 10 years or more. Yet the space programs in the United States

and Russia are desperate and immediate efforts. Why?

If it were merely a matter of developing weapons, you can bet there wouldn't

be half the publicity. The real and very vital issue is prestige. Democracy or communism

- which system can take man the farther faster? Outer space certainly isn't the

only test, but it is the most dramatic and clear-cut one. And right now the free

world is losing the ball game - and not because we lack technology!

As we go to press, Russia has successfully launched three satellites and one

space probe. The United States has countered with two space probes and six satellites.

But hits don't necessarily win ball games and these figures aren't winning the space

race. They convince the average American. So what? He was already sold!

Turning the coin over, it's a pretty safe bet that Russia has juggled the facts

and convinced Ivan that his own country is white-washing Western competition. And

there isn't very much we can do about this. What's at stake? Those nations and their

peoples who are neither communist nor solidly in the western camp - the hundreds

of millions in Africa, India and Southeast Asia, and those of our allies who lack

confidence in Western achievement.

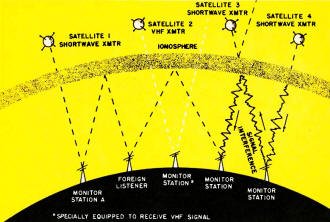

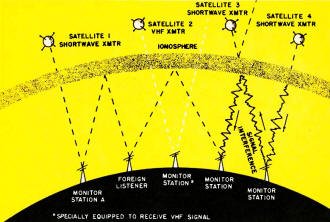

VHF is more reliable than short wave, but short wave reaches

more listeners. SW signals from satellite pass through ionosphere and skip between

it and the earth many times. They are heard not only by monitor stations, but also

by almost anyone with an SW receiver. One drawback: direction finder receiving a

second or third "hop" signal will give false satellite position. VHF signals from

satellite 2 travel reliably in line of sight to monitor, but reflected signals go

right back into space. SW is subject to ionospheric disturbances while VHF transmissions

are not. Signals from satellite 3 did not even penetrate ionosphere and those from

satellite 4 are garbled.

If these people in foreign lands could actually hear a satellite or lunar rocket

- not a rebroadcast - they would have something fairly tangible to hang their belief

and admiration upon. If they happen to be interested enough to request confirmation

of the signals and receive an attractive QSL in return, then so much the better.

This is exactly the kind of "tangible" proof the Russians are providing.

All Russian space vehicles have transmitted on short wave around 20 mc. All successful

U.S. space vehicles have sent back tracking and telemetering signals via the higher

frequency VHF. As a result, many thousands of persons throughout the world have

been able to hear the satellites launched from the USSR, while only a mere handful

with special equipment have been able to listen to their American counterparts.

Short wave is reflected back to earth by the ionosphere and because there is

little absorption of short-wave frequencies, signals often can be heard clear around

the globe. On the other hand, VHF signals do not "hop" between earth and ionosphere.

Reception is usually limited to line of sight. In other words, the signal from the

satellite transmitting VHF goes directly to the monitoring station.

The Russians have even gone so far as to verify reception of their sputniks and

lunik. I personally have received an attractive QSL card from the Russians for my

report on Sputnik I. Thousands of other short-wave listeners around the world have

received the same. It reads:

To Mr. C. M. Stanbury, observer of the Soviet sputniks, the first artificial

earth satellites in the world. Thank you for your reports. The information is of

scientific value and will be used in the processing of material in accordance with

the program of the International Geophysical Year. We hope to receive further reports

of observations from you in the future. The U.S.S.R. Committee on the International

Geophysical Year

The conservative tone of this QSL gives it greater propaganda impact. And the

repeated allusion to the International Geophysical Year makes it sound as if the

Russians were really trying to cooperate with that distinguished worldwide scientific

effort.

Editor's Note

An official spokesman for the National Aeronautics and Space

Agency (NASA) in Washington has informed us just as we go to press that Explorer

VI will be carrying 20, 40 and 60 mc transmitters - a departure from previous satellite

communications. Space and weight problems in earlier launchings precluded inclusion

of such a complete communications package, but more powerful rockets, such as Juno

II, now permit heavier payloads. Also it has been pointed out that a 20 mc transmitter

had been installed in an early Explorer satellite which, unfortunately, failed to

enter orbit. We have also been informed that NASA does not plan to QSL satellite

re- ports. They want to keep our space program on a high, scientific level and will

continue to rely on the government-sponsored Minitrack network for tracking reports.

However, Electronics Illustrated has learned that NASA certainly would welcome tape

recordings of satellite signals taken off the air by shortwave listeners and radio

amateurs, if these recordings are accompanied by complete reception information.

However, the fact that the Russians did not use an IGY recommended frequency

(around 108 mc), and the fact that they did not see fit to announce the satellite

launching until after Sputnik I was in orbit, points to non-cooperation rather than

cooperation.

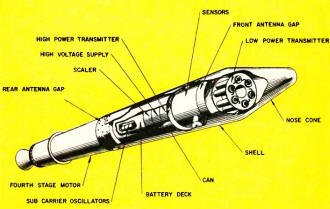

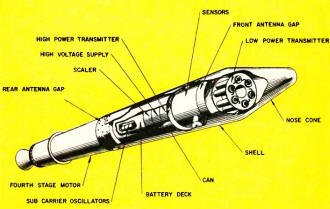

U.S. "talking" satellite is ready to be launched, but few heard

VHF signal. Bottom of page, diagram of Explorer IV radio set-up.

Taking the Russians' invitation to submit further observation reports at face

value, I hurried to my receiver upon hearing the announcement of the launching of

a Russian lunar rocket, now called Lunik. At about 2253 GMT on January 3rd of this

year, I tuned to 19.995 mc. About 5 kc below WWV I heard what sounded like a 300

cycle modulated continuous wave. The next day I heard the same signal, but weaker.

I wrote to the Academy of Sciences in Moscow and received a reply dated February

6, 1959. It was signed by the Academy's scientific secretary. That letter is reproduced

on these pages. Translation reveals that the Russians confirmed my first report,

but expressed doubt about my second report since the lunar rocket no longer was

a lunar rocket, but rather a cosmic one heading into orbit around the sun.

Why are we using VHF? For some excellent technical reasons. From the start, our

space program, now directed by the National Aeronautics and Space Agency, has been

a scientific data-gathering endeavor, not a propaganda effort. VHF is far less subject

to interference than short wave and therefore a more reliable means of transmitting

data. With short wave there is the danger of the ionosphere, under certain conditions,

completely blocking the signals off from the earth. Also, short wave's multi-hop

reception could result in ambiguous tracking reports making the satellite appear

at a point in the heavens far removed from its actual position.

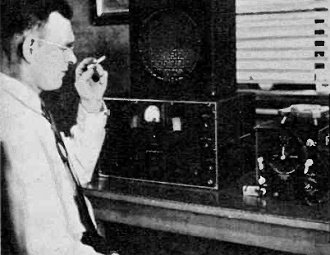

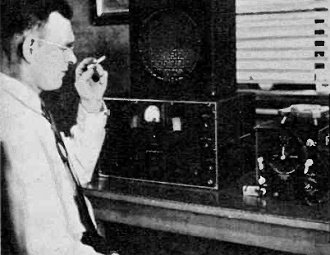

Author monitors gear that picked up Sputnik I and Lunik. Hammerlund

ham set feeds signal to GE aero receiver for further amplification.

From a data -gathering standpoint, VHF telemetering and tracking are technically

superior and the United States should continue using VHF. However, how about also

installing a simple, inexpensive short-wave transmitter in at least one satellite

and possibly one space probe? Power could be provided by small, but long lasting

batteries. Sputnik I, the most widely heard of all the space vehicles, used only

one watt and yet its signals frequently bounced around the globe.

Such a short-wave transmitter in an American satellite may be operated exclusively

for foreign listeners and amateur monitors, or it could be used to transmit scientific

information. Of course, a repeater tape loop bearing a voice message would be highly

effective as a propaganda gimmick, although higher power and a more complicated

transmitter would be required.

Signals from a space probe would, of course, have to span much greater distances

than those from an orbiting satellite. Again, small lightweight batteries could

be used, but with higher power compensated by shorter life, say two or three days.

The additional cost of such a project would be small beside the millions of dollars

spent on the Voice of America every year. The cost of mailing a QSL card by the

government would also be small, yet would certainly pay off in added prestige for

America.

|