|

<Previous

Next>

1973 letter of praise for Kirt Blattenberger, from

administrator of Annapolis Vocational Technical Centers.

One day in late spring of 1973 I found myself walking around the gymnasium of

Annapolis Junior High School (AJHS) trying to decide which courses

I would prefer upon beginning tenth grade the following fall. It was one of the

final days of ninth grade, which had been by far my least happy year in school.

Living in Mayo, Maryland, I and my fellow neighborhood ninth graders should have

attended Southern Senior High School

(SSHS) in Harwood, Maryland, where our predecessors had gone for ninth grade, but

overcrowding caused the Anne Arundel School Board wizards to decide that for at

least that year, we would remain at AJHS for another term. Historically, kids from

my area went to AJHS only for seventh and eighth grades and then switched to SSHS.

Annapolis, being the capital city of Maryland, was significantly more urban than

the rural areas to which SSHS type people were accustomed. The clientele was much

more aggressive in the big city. Sure, we had our "red neck greaser" rowdies in

the southern part of the county, but at least their parents would whip them if they

got caught getting into trouble. The north county parents, we believed at the time,

must have been rewarding their kids for daring to challenge authority. I was looking

forward to getting out of AJHS after eighth grade, and was devastated when I learned

I would be returning for ninth.

This article was retrieved using a subscription to

NewspaperArchive.com

The following caption text is provided to facilitate people doing Internet searches.

Jeanie Graves, Annapolis High senior, practices hair setting

techniques learned during a three-year cosmetology course in Annapolis.

Koons Ford point department supervisor Phil Brown oversees Archie

Brown's work in the body shop. Archie is a senior at Annapolis High.

Annapolis High School senior Jackie Middleton works with Miss

Nunley, food food services instructor, to master cooking, skills, to use at home

and work.

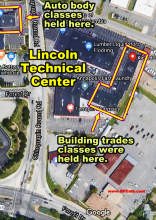

Mike Guy, 10th grader from Annapolis Senior High, works with

carpentry instructor Marv Holland at the Lincoln Vocational Center in Annapolis.

Working under the hood of a car, Tom Rachels of Severna Park

High School says the auto mechanics program is the reason he didn't drop out.

To make matters worse, AJHS was overcrowded, too, so the school went on split

sessions where the Annapolis area students had classes in the afternoon and we had

ours in the morning. The bus picked us up at a little before 6:00 in the morning

and returned us by about 1:30 in the afternoon. The ride was about 40 minutes each

way.

Getting "jacked up" in a bathroom, locker

room, or on the sports field was a regular occurrence. I learned to not drink anything

all day long so as not to have to use the bathrooms. Somehow three years passed

without my being physically abused, but a few of my friends got beaten up and robbed.

One kid I knew had his head bashed in by a gang hailing from a housing project on

the other side of a tree line next to the baseball fields. He have as much money

as his attackers thought they deserved, so they took the cutting board project he

was carrying from woodshop and doinked him with it. He spent the rest of the school

year and summer recuperating in the hospital and needed to repeat ninth grade. Click

on the thumbnail image to the left for the front page article reporting on the attack.

A tall chain link fence with barbed wire at the top was installed shortly thereafter. Getting "jacked up" in a bathroom, locker

room, or on the sports field was a regular occurrence. I learned to not drink anything

all day long so as not to have to use the bathrooms. Somehow three years passed

without my being physically abused, but a few of my friends got beaten up and robbed.

One kid I knew had his head bashed in by a gang hailing from a housing project on

the other side of a tree line next to the baseball fields. He have as much money

as his attackers thought they deserved, so they took the cutting board project he

was carrying from woodshop and doinked him with it. He spent the rest of the school

year and summer recuperating in the hospital and needed to repeat ninth grade. Click

on the thumbnail image to the left for the front page article reporting on the attack.

A tall chain link fence with barbed wire at the top was installed shortly thereafter.

Given all that background information, you might reasonably conclude that no

force on Earth could cause me to voluntarily spend any more time in school in Annapolis.

However, that aforementioned day in the AJHS gym found me being attracted to a special

display which had been set up by the folks who ran the building trades vocational

center for high schoolers. The college-bound crowd formed lines eager to get admitted

into tenth grade algebra and pre-calculus courses, chemistry and biology, American

literature, and archeology. Eschewing at the time any white collar aspirations,

preferring instead to work with my hands and my head, I permitted myself to be lured

into the Electrical Vocational program at the Annapolis Vocational Technical

Center.

Having always been a tinkerer of things mechanical and electrical, the opportunity

to spend my high school years learning about electrical theory, the

National

Electric Code, and performing hands-on wiring of motors, controllers, and residential

and commercial wiring was very appealing. The only hitch was - you guessed it -

doing so would require spending half of each school day in Annapolis at the Lincoln

Technical Center. It would also require once again catching an early bus that drove

many miles to pick up the relatively few students who were in the vocational program.

After classes ended around noon, another bus ferried us all to Southern Senior High

School where we attended various other requisite classes in order to meet graduation

requirements. Fortunately, and it was no small part of the draw for me to the electrical

vocational curriculum, the classroom portion of each day's session fulfilled requirements

for math and science. Our instructor, "Russ" Lorenson, himself a licensed electrician,

taught us all we needed to know about Ohm's law, magnetism,

Thévenin's

and Kirchhoff's laws, etc. For half the school day we were treated

more like fellow construction workers than high school students. There was always

colorful language, a hot pot of coffee and a limited amount of cigarette smoking

was allowed inside as long as no one complained - which no one did. Political correctness

had no home in our vocational classrooms.

We even had a

roach coach make the rounds each day during break time to sell

overpriced food and drinks.

One entire wall, compliments of the carpentry troops next door, of the electrical

room was a mock-up of typical house construction complete with door and window openings.

Teams of guys drew up wiring diagrams and parts lists according to specifications,

did all the wiring, and generated parts and labor bills. Our instructor, whom we

addressed by his first name (not typically done in the 1970s), would create problems

that we needed to troubleshoot and correct. The same was true for the motor control

and industrial automation circuits we would wire up and get working. We also learned

how to rebuild AC and DC motors, properly solder and tape wire splices, and how

to properly route and install cables and metal and PVC conduit.

During the second half of year two, the carpenter class built a bungalow-size

house inside the building, with the masonry guys providing a brick facade on the

front and a fireplace. The plumbers roughed in the pipes and we electricians roughed

in the wiring during construction, and then did the trim-out work (installed devices

and fixtures) once the walls were done. Interestingly, there was no class of drywall

finishers, so the sheets of drywall were nailed on but no joints were finished (other

than the ones finished behind the building by potheads).

The third year, senior year, those of us who remained in the program went to

our high school classes for the first half of the day and then left for work release

the rest of the day. I got a job working for Bausum & Duckett Electric (B&D) in Edgewater, Maryland,

where most of the time I ended up doing stockroom work and delivering parts to job

sites. B&D was one of the largest electrical contracting companies in the county.

Another fellow Electrical Vocational classmate of mine, Caroll W. (aka "Skeeter"),

who came from Annapolis

Senior High School and built an incredibly souped-up big block '68 Camaro, also

worked there with me. He came up with an unofficial slogan for the company which

all the "real" electricians loved but were forbidden from using outside the shop:

"We're Bausum and Duckett. If we can't fix it, f*** it."

It was a great experience from beginning to end. We had guys from many high schools

in the county, and everyone got along... most of the time, anyway. The vocational

school incorporated not just the building trades - electrical, carpentry, brick

laying, and plumbing - but also auto mechanics and body repair. It even had programs

for hair stylists and food service (cooks). The article below from the February

3, 1973 edition of the Evening Capital newspaper, where my father worked

as the manager of the classified advertising department, reports on the programs.

It was written the year before I began there. My best friend at the time, Jerry

Flynn, was a year ahead of me and was in the auto body repair course. He was a true

artist with body putty and a paint gun. In fact, Jerry painted my

1960 Camaro SS.

Contrary to the implication by the writer that most guys who were in the vocational

education program were only there as an alternative to dropping out of school, all

of the ones I knew were there because they wanted to learn the construction trades

or car maintenance - not a last-ditch effort to stay in school. After graduation,

I went on to work for two other electrical contractors before entering the U.S.

Air Force in November 1978 to be an Air

Traffic Control Radar Repairman. Four years later after separation I went to

work as an electronics technician for Westinghouse Electric in Annapolis. After

moving to Vermont for another job, I completed my BSEE at the University of Vermont

in 1989. Thirty-one years later, here I am.

"It keeps them in school"

Evening Capital

Annapolis, Maryland

February 3, 1973

335 students like learning in vocational ed program

They're building a house, fixing fenders, preparing sandwiches and creating,

hair styles. Some of them say it's the reason they've stayed in school and not dropped

out. All of them say they enjoy their work and plan to use the knowledge and skills

they are acquiring after graduation.

Who? The 335 high school students in the Annapolis area who are becoming skilled

craftsmen through a vocational training program conducted by the Anne Arundel County

Public Schools.

They take courses in English, history and math at their home schools during half

of the school day and spend the other half in vocational classes at the Lincoln

Vocational Center on Chinquapin Round Road (for auto mechanics, carpentry, masonry

or electricity), the old Shaw Building (for auto body and welding), or Annapolis

Senior High School (for food services or cosmetology).

As Gair Neitsche, a Severna Park High School student currently enrolled in the

auto mechanics program, put it: "I wasn't interested in school, wasn't doing very

well, but I've been around cars for a long time, this program is good experience,

with someone around to answer your questions, tools to use that you could never

afford to buy. I'm enjoying this. I'm going to use it."

Another auto mechanics student, Tom Rachels of Severna Park High School said

"I've waited for years for this program. I wouldn't have finished school if there

hadn't been something like this. The more effort you put into it, the more you get

out of it."

Richard Johnson and Bob Cook are instructors in the auto mechanics course in

which 87 students are enrolled. Harrell Spruill teaches an additional 48 youngsters

in the auto body and fender courses. Like other vocational education programs, these

courses combine "book learning" with practical experience. During senior year, the

top students are eligible to participate in a work-study program in which they hold

part-time jobs and get paid by their employers. Three work-study students in this

year's senior auto mechanics class have been offered fulltime jobs after graduation.

"In addition to learning a marketable skill, the kids are taught to get along

with people," according to vocational counselor Dick Peret. "We try to instill self

pride. I think they work harder because they know people are judging the program

by their performance," he said.

One local employer who shares this feeling is John S. Riley, service department

manager at Koon's Ford. "The boys we've gotten from the program have done very well,"

Riley said. "They get to work on time. They have good working habits. They are very

cooperative."

"They have helped us tremendously in the amount of service work we can do. Actually,

these boys work harder than kids we could hire off the street who hadn't been in

a program like this one," he said.

Perry Meyett, a work-study student, is enthusiastic about the program. "I think

it is the greatest there is. I've been here over a month and hope to keep working

here. I even do a little better in school now," he said.

"I'm tired from working I stay home at night and do my homework," he added. Meyett,

a member of Annapolis High's wrestling team, finished second in countywide competition

last year.

Ralph Jones, a graduate of the masonry program, works as a bricklayer. "I got

a skill out of the program and knowledge," Ralph said. "It really taught me something,

but I would have finished school anyway." Ralph is a former centerfielder for Annapolis

High's baseball team.

Leder Johnson, another graduate of the vocational program, received his diploma

from Bates High School in 1969. "I heard about the program during junior high school,"

Leder said. "The masonry trade was what I wanted to do to create and build things.

And now I'm doing it." Today, he is employed as a bricklayer in Annapolis.

"Doc" Jones teaches masonry. His students are building a retaining wall at Annapolis

Senior High School and helping to build a house inside the classroom at Lincoln

Center. The house is a joint project of the masonry, carpentry and electricity classes.

After the masonry boys lay the foundation, Marv Holland's carpentry students do

most of the work. "They read the blueprints, put up the walls and ceiling, lay floors

and do the finished woodworking. It takes about a semester to complete it." Holland

said.

Mike Guy, a tenth grader from Annapolis Senior High, is looking forward to his

apprenticeship in carpentry after graduation. One of 37 students in the carpentry

program, Mike said, "I wanted to work with wood, to learn a trade that would let

me work with wood. This program is a good way to get that skill." Last year, the

carpentry class restored the concession area at Annapolis High's athletic field

and paneled the program's administrative offices in the old Shaw Building.

When the carpenters have completed the frame and are ready to wall the house,

members of Russell Lorentson's industrial electricity class wire it. Dan Carver

transferred from Arundel High to Annapolis because of the industrial electricity

course offered here. Thirty-four boys are currently enrolled in the program.

"I was going to quit if I hadn't gotten into this one," Dan said. "There wasn't

anything in school I wanted. Now I'm learning to wire a house. It's a life career.

I can still go on to be an architect if I want to. I almost made the honor roll."

"When my friends heard I was learning cosmetology in school, they were sorry

they didn't have a program like this one," said Linda Shellman, an eleventh grader

who is studying cosmetology at Annapolis High.

Asked about her plans after graduation, Linda said "If I'm good enough, I'll

take the state board exam. If not, I'll go to a beauty academy and take the state

test when I'm ready."

Mrs. Huddleston and Mrs. Holland, instructors at the cosmetology lab in Annapolis

Senior High School, give their 65 students practical instruction and background

in theory to prepare them for a test by the Maryland State Board of Cosmetology

after graduation. Before taking the test, the girls must have 1,500 hours of combined

practice and theory in cosmetology. A student can meet that requirement by entering

the program at the beginning of the tenth grade and maintaining a good attendance

record.

Jane Bowen, a junior at Annapolis High, recently took second place in a contest

for beauticians sponsored by the Maryland Board of Cosmetology at the Baltimore

Civic Center.

"I was surprised that I did so well in the contest," she said. "I hope to finish

the course. I don't find it difficult. the important thing is to pay attention in

class, and that's not hard if you are interested."

Jenny Graves will be the first graduate of the three-year course. The Annapolis

High senior chose the program at the beginning of her freshman year because she

liked doing her friends' hair.

Jenny admitted that she found the theory sessions somewhat difficult "You really

have to put your mind to it," she said. To become a licensed cosmetologist, she

must pass the state board exam, which she plans to take after graduating in June.

If she wanted to open her own beauty shop, she would have to serve a year's apprenticeship

and another year as a junior manager. After completing this two year requirement,

she could become a senior manager and open her own shop. Miss Graves may not follow

that route, however, she has expressed an interest in teaching cosmetology.

Across the corridor from the cosmetology lab, Miss Nunley holds classes in food

services for 30 junior and senior high school students. Bruce Wells, a senior, is

working part-time at the Harbor House in Annapolis. Jackie Middleton another senior,

claims that she enjoys the program because she likes to cook and can use the skills.

"It isn't hard because I am interested," she said.

Paulina Porter, a junior who moved to the area from New York, finds the course

helpful because "they teach you things that you need to know when you want to get

a job. It's something you can use now."

"Something you can use" is the key to most student's interest in the vocational

education program. Not every student can see the usefulness in studying academic

subjects. Not every student choses to go to college.

"I was never an academically-inclined kid myself," admitted John Killian. Killian

directs the program in Annapolis under the supervision of vocational administrator

Bill Otto.

A former shop teacher, Killian said, "I could work with kids in shop because

there was an informal atmosphere. I could help develop other interests, develop

an interest in math, for instance, because it applied to what they were doing."

The real significance of this program, as Killian sees it, is that it saves kids.

"It saves them from dropping out of school," he said.

"The kids in this program can become something," Killian said. "They have no

trouble getting jobs. My only regret is that we can't accommodate each child who

wants to get into the program."

In addition to the trade and industrial program at Annapolis, the local school

system maintains a vocational technical center in Glen Burnie, and a few courses

are offered at Southern High School. Distributive education, office education, data

processing, health occupations and cooperative occupancy programs are available

to students in all senior high schools in the county. Homemaking programs are available

in all junior and senior high schools.

|

"

"