As radio frequencies moved

up into the UHF realm of

30 MHz (through 3 GHz), designers noticed that the old methods and equations

for winding inductors (aka coils and chokes) no longer performed as predicted. The

culprit was stray capacitance created by the wire itself and the insulation between

windings. To some extent, the length of leads running from the inductor windings

to connection points (terminal strips and lugs at first and then later printed circuit

boards) generated enough extra inductance to add noticeably to total inductance.

New methods were developed to help mitigate the effects of these stray (aka parasitic)

reactances. Much new knowledge in this area was gained through the war efforts with

many radar and radio designs coming online during the time.

R.F. Chokes at U.H.F.

Fig. 1. Photographs of several r.f. chokes that can be used

depending on the operating frequency. (1) Broadcast type coil, used effectively

up to 10 mc. (2) Used extensively at frequencies from 10 to 180 mc. (3) Air-core

type solenoid used at higher frequencies.

By W. J. Stolze

With the assignment of many services to higher frequencies, the electrical

characteristics of component parts must be carefully analyzed.

With the advent of FM and television, the radio serviceman, who for the past

twenty-odd years has been ably repairing amplitude-modulated (AM) broadcast receivers,

must now familiarize himself with good design and construction technique in the

recently assigned high-frequency bands. A thorough working knowledge of the various

problems which become apparent at high frequencies will not only increase the pleasure

that a radio amateur can extract from his hobby, but will also be very profitable,

for in the immediate future the majority of sets brought into the small service

station for repair will be high frequency FM and television receivers. With an eye

to the future, this article will discuss the design and application of radio frequency

chokes in the new v.h.f. bands.

The proper selection of a correct r.f. choke, even though often ignored, misunderstood,

and underemphasized, is an important factor in obtaining the best possible performance

from a well-designed unit of equipment. The most important circuit application of

the choke is in series with the B+ plate voltage supply of high-frequency oscillators.

In Fig. 3A a typical FM local oscillator is shown. The choke, RFC1

is inserted in series between the plate of the tube and the B+ voltage supply. At

the frequencies used, if this choke were not present a portion of the available

power output of the oscillator would be dissipated in the plate power supply. This

is a serious situation when maximum power output is required. The condition can

be equated as follows:

Power Output = Power Available - Power Dissipated

A typical circuit uses the 6C4 and is capable of delivering about four watts

maximum output. With improper choking, as much as two watts may be lost in the power

pack, leaving only two watts, or 50% maximum power, available as useful output.

This condition also exists and is even more serious in high power transmitter oscillators.

Fig. 2. (A) In higher frequency applications r.f. chokes

must be employed in the filament circuits to prevent oscillations. Proper method

of grounding is shown. (B) Circuit for grid bias modulation. R.f. choke prevents

r.f. from entering modulation transformer.

Fig. 3A also includes a choke, RFC2, in the grid-leak circuit.

Most setups require this choke, as its omission may be cause for the oscillator

to cease operation. A diagram of the typical grid-leak resistor is shown in Fig. 3B.

A carbon rod forms the resistive element, which is flanked on each side by small

round metal plates, A and B from which the terminal leads are brought out. Bakelite

or ceramic covering is added as insulation. A stray capacity exists between these

plates, A and B, which at high frequencies may be of such magnitude as to bypass

enough of the signal from the grid to ground to prevent oscillation.

In the 200 to 600 megacycles per second section of the frequency spectrum, transmission

lines make then appearance as tuned circuits for power oscillators. At these frequencies

another problem appears. High percentages of the power may run down the leads of

the filament and be lost in the filament transformer. Correction of this condition

is essential since the same problem exists as did with improper plate supply chokes.

Fig. 2A illustrates the application of r.f. chokes in the filament leads, and

one of a number of correct methods of grounding. As the frequency approaches 600

megacycles, and above, however, it becomes convenient to feed the heaters through

tuned transmission lines, which then act as r.f. chokes.

Confining r.f. to particular sections of a circuit and eliminating it in other

sections is another use to which r.f. chokes are put in modulating apparatus. In

Fig. 2B a circuit for grid-bias modulation is shown. Here the r.f.c. prevents

the r.f. from flowing in the modulating transformer.

Of course there are many other applications of r.f. chokes, but those which are

most important and those which the average radio serviceman or radio ham are most

likely to encounter have been included in the above discussion.

Fig. 3. (A) Diagram of FM local oscillator, shows most common

application of r.f. chokes. (B) Common grid-leak type resistor.

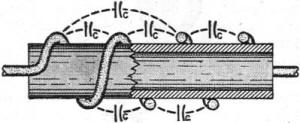

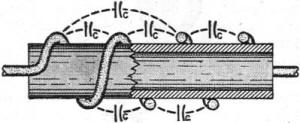

An important characteristic of chokes which is very often forgotten or ignored

is that the choke must be a very high impedance at the operating frequency and not

just a high inductance. If this condition is not fulfilled a serious detuning of

the tank circuit may result. This statement at first appears paradoxical, but can

be easily explained with reference to Fig. 5. It shows a number of coils of

wire wrapped around a Bakelite form. Small capacities (distributed) exist between

each pair of turns on the coil. Classically a condenser consists of two flat plates

of a conducting material separated by an insulating dielectric. In this case the

two turns of wire form the plates and the interspace air forms the insulator. A

condition of this nature exists with every coil. Even though the distributed capacity

is small, it is impossible to make it zero; therefore, the optimum in choke design

appears when the inductance of the coil resonates with its own distributed capacity

at the operating frequency.

In actual practice, self-resonance is almost impossible to obtain exactly, because

stray capacities which arise in the circuit wiring almost always detune the choke

somewhat, but a condition as close as possible to the goal will pay the highest

dividends. Too many turns will result in a very large stray capacity and, at a frequency

any appreciable amount above resonance, the choke will appear to be a shunt condenser.

A Boonton Q Meter is an excellent instrument on which to measure resonant frequencies

of chokes, but since such an instrument is expensive and therefore not available

to the average amateur, several graphs are included to aid in the design of high-frequency

chokes.

Other characteristics of chokes that are important are the current carrying capacity

of the wire, which must be high enough for the desired application, and the resistance

of the choke, which must be low enough not to cause an appreciable voltage drop.

Remembering this construction hint will save many hours of time search-ing for

the cause of trouble in new FM sets.

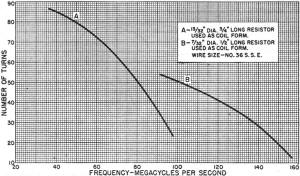

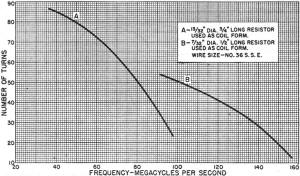

Fig. 4. Design chart shows approximate number of turns vs.

frequency for r.f. chokes.

Fig. 5. Distributed capacities that will have effect on

the operation of choke.

Now for a sample design of a choke.

Sketches of several chokes used at various frequencies are pictured in Fig. 1.

Type 1 is used mainly in the broadcast band and up to approximately 10 megacycles.

Construction of this of choke is difficult, as it necessitates the application of

a universal coil-winding machine and is therefore out of the scope of most amateurs

and radio builders. Choke number 2 is useful for frequencies from about 10 megacycles

up to about 180 megacycles. Above this frequency, air-cored solenoids, type 3, are

used.

Ceramic insulated resistors, with values ranging from 1 megohm up, provide the

best form on which to wind a home-constructed choke. This material has about the

least losses of any readily available. Isolantite is used commercially, but this

is essentially the same thing. The 1-megohm resistance is high enough so that its

effect upon circuit Q's is negligible. Another advantage of a resistor is that its

terminal leads are excellent in facilitating the use of short connections.

All choke connections at high frequencies should be as short as it is possible

to make them. This point cannot be overemphasized, as long leads add dangerous amounts

of inductance and capacitance at the frequencies used in the new FM band.

An excellent illustration of this condition can be shown by the following analogy:

A lead 1" long at 100 megacycles has the same inductive reactance that a lead 8'4"

long has at standard broadcast frequencies. How absurd it is to think of hanging

an 8-foot connection lead in an AM receiver.

Let's say a choke is desired for the plate circuit of a local oscillator of an

FM set (Fig. 3A). An excellent high-frequency oscillator tube is the Radiotron

6C4 miniature triode. The first factor that comes into consideration is the current

that the plate will draw at maximum output. In the design chart shown in Fig. 4,

values are given for chokes wound on two different sized cores, using No. 36 single

silk enamel wire. The No. 36 wire can carry 25 milliamperes. One watt, 13/32" -diameter,

and one-quarter watt, 7/32" diameter, ceramic insulated resistors are the two sizes

of forms covered by the chart. Plate current in a small receiving tube is generally

not over 25 milliamperes, so the No. 36 wire will suffice for this circuit.

A point in the middle of the band is the optimum frequency to choose for the

design. The present band is 88 to 108 megacycles; therefore, 98 mega-cycles will

be the design frequency for our choke. On the chart, using a 7/32" form, it can

be seen that 51 turns will fulfill the specifications.

To begin construction, sandpaper the marking paint off the body of the resistor

and solder one end of the wire to a terminal lead. After winding the required number

of turns, cut the wire to size and fasten it to the other lead with solder, being

careful to keep the coil tight, neatly wound, and closely spaced. If the design

chart has been followed with any degree of accuracy, a choke has been made that

is applicable in either the plate or the grid leak circuit of the oscillator, RFC,

and RFC, of Fig. 3. Two identical coils should be wound.

All the design and construction de-tails presented in this article are important.

Following them will not insure success, of course, but it will certainly be a tremendous

aid. The following are a number of general construction rules for u.h.f. work:

1. Keep all leads as short as possible;

2. Construct the chassis, circuit. and other parts sturdily;

3. Do not use inferior components. Even though u.h.f. is a new field, the amateur

or radio serviceman should not hesitate for a moment to enter it, for it is an unexplored

wilderness with great opportunities for fascinating home research.