Carl & Jerry: Eeeeelectricity!

|

|||||||

Wikipedia claims there are about 350 species of electric fish. Jerry tells fellow electrical and electronics experimenter Carl that the electric eel is not an eel at all, but a fish. Actually, the eel is a fish (a knifefish); however - and I needed to look this up - a true eel is a member of the fish order Anguilliformes, which the electric eel is not. Having no expertise in the field of eels, I'll leave it at that. Jerry's uncle, who is an active duty Navy guy, somehow managed to ship an electric eel to him for experimentation purposes. Doing so might have been possible in 1956 when this episode of "Carl & Jerry" appeared in Popular Electronics magazine, but today it is doubtful. Besides that, how to you mail an electric eel to somebody? The pair's measurements of voltages and pulse widths jive pretty well with modern data. Here is a story about how electric eels curl to obtain higher voltages for stunning prey. Carl & Jerry: Eeeeelectricity!

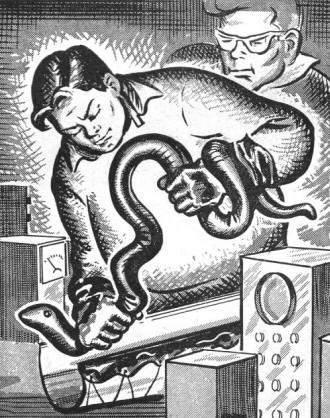

Carl was just arriving home after spending a short week-end vacation with an aunt and uncle in Chicago. He burst in the front door, yelled "Hi, Dad," planted an awkward kiss on the bridge of his mother's nose; and sailed right on out the back door, across the yards, and into the basement laboratory of his neighbor and best friend, Jerry Bishop. Jerry was there all right, and he was just as glad to see his pal as Carl was to see him; but it was against the Code of Boyhood to show their feelings. Jerry hardly looked up as he grunted a greeting. To tell the truth, though, he was pretty busy trying to strap a squirming, wriggling something into the concave side of a short section of gutter trough. It kept slithering through the rubber gloves he was wearing. "Holy cow, Jer, what is that thing?" Carl demanded. "Is it a snake?" "Of course not, stupid. It's an eel that my uncle in the Navy sent me from South America. I want to make some tests on it. Put on that other pair of rubber gloves and help me fasten it in this trough." "Not on your life!" Carl said emphatically as he backed toward the door. "I wouldn't touch that snaky-looking thing with a ten-foot pole, let alone my hands. Why on earth would your uncle send you something like that? Has he sprung his hatch?" ... Jerry was trying to strap a squirming, wriggling something into the short section of gutter trough, but it kept slithering through his rubber gloves ... from a story that appeared in the June-July, 1956, edition of a storage battery house organ called Exide Topics that my uncle sent me. What I want to do right now is to double-check on some of the statements in that story." "Certainly not. This is not just an ordinary eel. In fact, it's not really an eel at all. Strictly speaking, it's an electric fish . My uncle says if I'm going to be an electronics engineer I should know about all forms of electricity; and electric fishes have been stirring electrons for thousands of years. Pictures of them appear in Egyptian tombs and they are mentioned in Aristotle's Historia Animalium. In addition to this so-called electric eel, there are five other fishes with shocking power: the torpedo or electric ray, the electric catfish, the star-gazer, the numb-fish, and the elephant-snout fish." "Never mind the lecture, Professor," Carl said impatiently. "Just tell me what you are trying to do with old Squirmy there." "I want to strap him in this rubber-lined trough so I can find out something about the electric charge he emits. The rubber lining will prevent his being short-circuited by the metal trough. When I get him fastened down, I'll slide these little tin-foil strips underneath his body at different points to pick off the charge he emits. Then, by using the 'scope and the VTVM, I'll know if he has a.c. or d.c. wiring and how much voltage he puts out." "You mean you don't have any idea what to expect? And are you wearing those rubber gloves because you don't want to touch the slimy thing or because you're afraid of being shocked?" "To answer the last first, I'm wearing them cause I don't want to be shocked. A full-grown electric eel can put out a jolting five-hundred volts that can stun a horse or paralyze a man. Since eight feet is about as long as they get, and since this one is nearly five feet long, I'd guess he was full grown. He acts fully charged, too. An adult eel that puts out only three hundred volts is either sick or simply not letting himself go. Even a baby eel can deliver around 120 volts - as much voltage as there is in the a.c. house line." "How do you know all this? You been boning up at the library?" "Looks like you've got Old Squirmy pretty well trussed up; so let's start double-checking," Carl suggested. "Okay," Jerry agreed. "First let's see if this eel is a.c. or d.c. According to the eel experts, the electrical discharge he puts out is a series of rapid direct-current discharges in the form of short-duration pulses sent out at a rate of about four hundred per second. But these pulses are of such short duration, about two-thousandths of a second, that the actual wattage output of an adult electric eel is only about forty watts." Then suppose we hook Buster here to a forty-watt bulb," Carl suggested. "He's no good for lighting bulbs," Jerry explained." Those pulses are too short to overcome the thermal lag of an incandescent bulb filament. Voltage has to be applied to such a filament for about one-fiftieth of a second before it begins to glow, and one of these pulses only lasts about one-tenth that long. But he could light a neon bulb, and I'm sure he'll make some interesting traces on our 'scope. I've got an idea about how to check his polarity, too. We'll simply run his output into this 0.5-microfarad capacitor and let him charge it up with his pulsating voltage. Then our VTVM connected across it will show his peak voltage and polarity." As he talked, Jerry slipped one tin-foil electrode beneath the tail of the eel and another beneath the center of his body. Leads from the electrodes went to the capacitor, and the VTVM was connected to read the voltage charging this capacitor. "Three-hundred-and-fifty volts!" Carl announced; "and the way the pointer swings proves that Old Squirmy's tail is the negative pole of his battery and the front part of him is the positive pole." "Watch the meter while I slide this front electrode back and forth," Jerry suggested. "I want to find where the front end of his generator actually is." This method soon showed that the maximum voltage, four hundred and eighty volts, was obtained when the negative electrode was at the eel's tail and the positive electrode was at a point about a foot back from his head. "That squares with what the books say," Jerry reported. "According to them, all of the critter's vital organs are in the front fifth of his body, and the rest is made up of 'electric tissue.''' "Whatever that is." "It's a flabby whitish jelly composed of 92% water. This stuff is organized into three pairs of electric organs. The eel can use one pair for a major discharge, one pair for a medium-size whammy, and the third pair for a small shock. Each organ is made up of smaller units separated by another kind of tissue that acts like the insulating separators in a storage battery. The electricity is actually produced in these smaller units. Each one produces about one-tenth of a volt. Somehow, in some way, the creature is able to connect these units in series to produce the high voltage discharges. But how he can throw thousands of 'switches' on and off several hundred times a second in perfect unison is still a mystery." Jerry connected the leads from the electrodes to the horizontal input terminals of his 'scope and adjusted the linear sweep until he had two of the voltage spikes visible on the screen. Since the frequency of the eel's output was irregular, this pattern was not easy to hold, but a sweep frequency of around 200 cycles per second displayed two complete pulses. Once again this proved the books were right when they said that the eel put out about 400 discharges per second. "For the rest of our experimenting," Jerry mused, "we should have the eel swimming freely about. Wonder where we can manage that? He's too big for a washtub." Jerry and Carl looked deep into each other's eyes and saw the same thought. "Okay," Jerry said, "but you'll have to go ahead and make sure the coast is clear. Mom is deathly afraid of this thing, and if she saw us sneaking it into the bathroom, she would never set foot in there again." Jerry gathered Old Squirmy, still strapped to. the length of gutter trough, under his arm and cautiously followed Carl up the basement stairs. Jerry's mother, fortunately, was busy talking on the telephone and never noticed the boys tiptoeing past the door on their way to the second floor. Safely inside the bathroom, Carl started quietly filling the tub with water while Jerry made another trip to the laboratory for other equipment he wanted. When the tub was two-thirds full, the eel was released inside it. He seemed to enjoy his freedom and went slithering around on the bottom of the tub in graceful coils. Jerry separated the earpieces of a pair of headphones and handed one to Carl. "Listen!" he said, as he dipped the metal-tipped ends of the headphone cord in the water. Clearly heard in the phones was a static-like noise. When the eel was quiet, this noise subsided; but as soon as it started to move, the noise returned. "Any time he is moving," Jerry explained, "the electric eel gives off a series of weak discharges. These serve two purposes: first, they warn enemies to keep their distance; and secondly, they form a kind of radar that enables the eel - which is virtually blind when it is adult - to seek out its prey." Wait a minute!" Carl interrupted. "I'm not so dumb that I don't know a radar system consists of a receiver as well as a transmitter. I'll admit Old Squirmy has a dan-dan-dandy low-frequency transmitter; but where's his receiver?" "He's got one all right, according to the books," Jerry replied. When one eel in a tank discharges, all the other eels come to the spot, apparently to horn in on the result. Obviously they know when one of their fellows is trying to stun something and can judge very nicely where the current is coming from. But now let's see if we can prove this with the eel-caller I've built up. It's a blocking oscillator that produces sharp spikes of voltage over a frequency range which is adjustable from about 500 to 2000 cycles per second. The output of the oscillator drives an output tube so as to produce pulses of very respectable amplitude across these two electrodes. Let's place the electrodes in the water at this end of the tub and see if we can sweet-talk him into coming over." Carl did as he was told, and Jerry began varying the frequency of the blocking oscillator. As a certain frequency was reached, the eel on the bottom of the tub began to stir and swim directly to the electrodes. When they were transferred to the opposite end of the tub, he immediately moved toward them. "Old Squirmy's receiving frequency seems to be around 800 cycles per second," Jerry announced. "Say! That thing really puts the come-hither on him," Carl said enthusiastically. "We ought to patent it." "We're a little too late," Jerry told him. "Eel hunters in South America are already using earphones to locate electric fish and then are employing eel-callers something like this one to lure them into their traps. But to get back to his built-in radar, by means of it the electric eel can move straight toward his prey and can detect a variation of just a few inches. What's more, he can tell instantly if his prey is moving and can make allowances for that movement." You know," Carl mused, "that's all pretty wonderful when you stop to think about it. Here we think of electricity itself as being quite modern, but that ugly creature resting there on the bottom of the tub and his ancestors have been using electricity for thousands of years. What's more, they've been using it in ways that we think of as being ultra-modern. Since electric eels talk to each other by means of their electric discharges, we must admit that they are equipped with wireless telephones. Those same discharges are employed as a compact, efficient, and highly effective weapon to secure food and to combat enemies. Finally, the lowly eel has been quietly using radar - which we did not discover until the last war - for countless centuries. It kind of makes you wonder if man - in spite of all his scientific development and progress - is so doggone smart as he thinks he is, doesn't it?" "It certainly does," Jerry agreed, "and I think my uncle had something like that in mind when he sent me the eel and told me to study it. When we work with electricity that is man-produced by batteries and generators and so on, we sort of take it for granted and forget how magic it really is, but when you see electricity being generated within the living tissue of a live creature such as this, all the wonder and mystery of it sweeps over you, and you are glad that you intend to make a lifetime study of it."

Posted April 19, 2022

|

|||||||

By John T. Frye

By John T. Frye

Carl & Jerry, by John T. Frye

Carl & Jerry, by John T. Frye