How My Radio Helped Me Break the Transcontinental Air Record

|

|

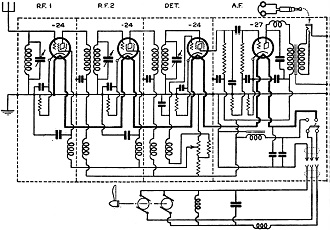

"Compactness distinguishes the Western Electric 8A airplane receiver." That statement describes a 160-pound system that included a wind-driven electricity generator for the equipment used by Captain Frank M. Hawks when setting coast-to-coast time records in the year 1929 using his Lockheed Air Express airplane, dubbed "Texaco 5." A simple 4-tube AM radio, its chassis measured a whopping 6" x 10" x 12". There were no radio direction finding stations enroute at the time, so the radio's usefulness was limited to being "comforting to listen in every half-hour and be advised of general conditions throughout the United States." Daring pilots of the day risked life and limb to push forward the frontiers of technology by testing and proving airframes, engines, electronics, navigation methods, and, almost as importantly, building confidence and a sense of awe and urgency on the part of the public so that continued development would be assured and encouraged. How My Radio Helped Me Break the Transcontinental Air RecordBy picking up weather reports I was enabled to avoid storms and fog and take advantage of favorable winds By Captain Frank M. Hawks The radio-equipped Lockheed Air Express flown by Capt. Hawks in his record-breaking flights Capt. Frank M. Hawks, holder of the East to West and West to East speed records, in the control cockpit of his plane Here is a complete Western Electric airplane receiver installation consisting of receiver, wind-driven generator and remote control panel Compactness distinguishes the Western Electric 8A airplane receiver used by Capt. Hawks in his transcontinental dashes. To the right, the circuit employed in the 8A receiver. It consists of two r.f. stages, a detector and one resistance-coupled audio stage. To those readers who are technically inclined and who might be interested in the characteristics of the West-ern Electric radio equipment which I used in my Lockheed Air Express, Texaco 5, the plane which holds both transcontinental speed records, I shall divide this data into two divisions. First, the electrical characteristics: This set covers a range of from 600 to 12,000 meters and is entirely remote-controlled. The circuit consists of two stages of radio-frequency amplification, a detector and one stage of audio-frequency amplification. Heater type screen-grid tubes are used in the r.f. and detector stages. This type of tube, used as a space-charge grid detector, permits very high sensitivity. The input or antenna stage is provided with a special input filter to avoid interference from unwanted stations. Second, the physical characteristics: the receiver is made of duralumin, and its dimensions are approximately 6" x 10" x 12". The weight is approximately 160 pounds. This receiver is arranged with its own shock-absorbing platform, permitting easy assembly and removal from the plane for servicing. There are two remote-control units, thereby permitting the receiver to be mounted in any convenient location in the plane. Located in the pilot's cockpit. they consist of a volume control and a remote tuning control. Usually the power is supplied to the filaments directly from a twelve-volt airplane battery, and a ballast lamp in the set automatically protects the tubes against the average battery fluctuations. A seven-pound dynamotor, operating from a twelve-volt airplane battery, supplies the plate potential to the receiver. However, in my plane, I use a small wind-driven generator which provides both the 'A' and 'B' supply directly to the receiver. This was done to aid in the elimination of excess weight, as it was necessary for me to carry 550 gallons of gasoline, weighing nearly 7,000 pounds, on my transcontinental hops. Radio now plays an important part in air navigation. The Department of Commerce has placed radio stations all the way across the continent for guidance of pilots by means of radio beacons. Every half-hour the beacon is shut off and weather reports are broadcast by voice on the same wavelength. In order absolutely to guarantee record time and to complete both non-stop hops successfully, it was necessary to have the best radio equipment installed in my ship. On the morning of the twenty-eighth, as I took off with a heavy load for the West from Roosevelt Field to lower the previous record of twenty-four hours, I was receiving weather reports from Hadley Field assuring me of satisfactory flying conditions over the first hazardous part of the trip, the Allegheny Mountains. After passing over Altoona, I began to run into heavy ground fog which covered the entire surrounding country. This condition is confusing to any pilot, but with my radio I was able to receive favorable reports of the weather and I knew that the ground fog was only local. The remainder of the day I was favored with splendid visibility. I did not need the radio; however, it was comforting to listen in every half-hour and be advised of general conditions throughout the United States. Upon arriving at Cajon Pass the entrance of the transcontinental route into Los Angeles, an immense ground fog lay over the entire valley, giving me considerable concern as to the landing possibilities. It was about eight o'clock in the evening and darkness was rapidly coming upon me. Once again the radio came to my rescue, and informed me that the Los Angeles Metropolitan Airport was open, and that the fog had not yet reached that area. On the return trip I was favored with good weather. But head winds, however, shortened my time record. The radio was used only as a comforter at the half-hour periods, but became valuable when I arrived over Columbus and nightfall came upon me once again. Clouds were rising rapidly to high altitudes, and it was necessary to fly blindly through them in my climb upward to get on the top. From Columbus on into New York there was nothing but a sea of clouds broken only at occasional points where I could see the lights of automobiles and towns through the holes. Without the use of radio I doubt if I should ever have continued because the weather looked more and more questionable as I kept speeding eastward, and it was out of the question to rely entirely upon my senses and unguided judgment alone. Here, again, the radio unquestionably was the greatest of help. and it made the flight a success. By its use, I was told the weather conditions and of the broken forecast over Roosevelt Field which would permit a safe landing, and I continued on through the darkness with the utmost confidence, arriving at Roosevelt Field in record time by some forty minutes. I am keenly enthusiastic over the use of radio in aircraft. On one or two occasions I have flown a plane not equipped with radio on cross-country trips. Each time I felt a though there was something lacking. I missed the comforting half-hourly news from the Department of Commerce radio weather stations and the steady buzz of the radio beacon. I always make it a point to fly over the airways as outlined by the Department of Commerce, because of their facilities to aid the pilot in air navigation. Still another experience helped to prove the value of radio. Immediately after the National Air Tour I took off from Detroit for New York with very questionable weather ahead. With twelve other pilots I headed for New York. We went through several severe snowstorms with negligible visibility and I am certain that I should never have continued if it had not been for the radio beacon and encouraging weather reports from the eastern end. I made the flight from Detroit to New York in three hours, which I believe is record time, whereas the other pilots all turned back at Toledo, and not one of them came through: They did not have radios. I believe that the time will come when there will be written in the air traffic regulations a special enactment calling for installation of radio on all aircraft. The aid which radio insures to air navigation is indispensable, and its use should be compulsory.

Posted June 19, 2023 |

|