Let's Listen for Mars

|

||

In the late 19th century, 1877 to be precise, Italian astronomer Giovanni Schiaparelli determined by observation and logical deduction that the maze of dark lines seen on the surface of Mars had to be of intelligent design (i.e., Martian beings) because no known natural process could possibly create such complex patterns. He called them "canali," meaning channels, or canals. This type of proclamation seeded the concept of extraterrestrials (ETs) being "out there" and most likely visiting Earth. American astronomer Percival Lowell (of Lowell Observatory renown) picked up on and amplified the Mars canals and oases theme through the early 20th century. In fact, it was not until NASA's Mariner planetary probes photographed Mars close-up that the theory was disproved and shows the real explanation was natural drainage paths which occurred when its CO2 polar ice caps melted. When this article appeared in a 1938 issue of Radio News magazine, many serious people believed there was animate life on Mars and other planets, whether of greater or lesser intelligence. Those rascally Martians were either not far enough advanced to contact us, or they were of superior intelligence and were smart enough to avoid us. Let's Listen for Mars

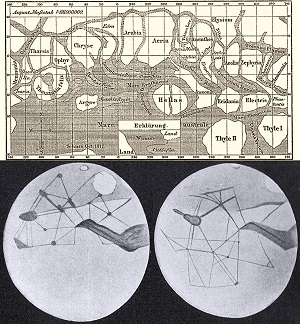

"Canali" on Mars per Schiaparelli (top) and Lowell (bottom). R. D. Hutchens Mars isn't very far from here. In 1924 it was only 35 million miles away. Compared with other astronomical distances, this is tantamount to snuggling. Radio signals have traveled farther than that. Scientist Jorgen Hals of Oslo, Norway, on February 2, 1929, received one that was missing for four minutes and twenty seconds after he sent it. During the interval it was going 186,000 miles per second, without being struck in ethereal mud, so that its journey covered nearly 50 millions of long miles. If you heard the Philippines last week, don't claim the world's DX record! Of course, you can be cynical and say the signal never reached another planet, but then you must be visualizing a concave reflecting surface 25 million miles from here - a ball with an inside circumference more than 150 million miles. If you can imagine that, it's but a step backward to admit communication with other planets is possible. Mars, being the closest, is the most probable. If it isn't, why did the French Academy of Science post notice of a cash award for the first person to establish two-way signaling with any heavenly body, except Mars ? Consider this red planet, and its similarity to ours: we know from spectra that its chemical, and hence molecular, composition is much the same as that of the earth. The U. S. Naval Research Laboratory, in an investigation of Mars' ionosphere, found skip distances during the Martian summer were best suited for communication on waves between 50 and 100 meters, and showed that nothing below 47 meters would be suitable for long distance contact between points on its surface, As on our planet, ether phenomena have existed since creation. Let's turn on our set; perhaps -? The canals of Mars suggest, by their geometrical pattern, an artificial formation. Mother Nature, here or there, seldom chooses such angular design. There - the short wave set is warmed up; let's start tuning. The background noise you hear isn't from a planet - it's smoke static. Our antenna is directly over a chimney, and when the furnace is cleaned, charged particles of soot bump against the wires. We hear rapid random clicks as they. discharge through the set to ground. It isn't very loud, but you should hear the same thing on a coal-burning ship, when the chief engineer is making extra steam so the skipper can blow the whistle! Stand by a moment, until they finish with the furnace, and we'll try something else. March 15th's on Mars are 687 days apart, in spite of anything the Department of Internal Revenue can do about it. Their orbit in the solar system is slightly greater than ours; their day is 24 1/2 hours; their diameter, a third of ours. So it's a small world, after all. Listen to this - sounds like a plane in flight. It's a code transmitter, running idle between message groups. Too fast to read because it's automatic, running at 200 words per minute. The record for aural reception is at one-third that speed. You hear 80 dots per second, and the swinging note is caused by slight fading when the signals are reflected to us by a billowing Heaviside layer. Of course, everything sounds like Mars if you don't know what the sources are. Reports of signals from the voids come in surges. Four years ago, as a result of many such reports, a group of pseudo-scientists in England, broadminded but sleepy; sat up all night before the controls of a specially-designed 24-tube receiver, listening for planets. They reported funny noises, which, considering the possible gain of such a rig, might well have been the swish of electrons between the cathode and plate of the first tube. Or perhaps they were head noises. Hear those clicks? No use trying to tune them out; they aren't on any particular wave. Reminds you of a telegraph sounder; the spacing is what suggests it. Something like this: •• •• •• •• •• •• In International Code, it means nothing; in Landline Morse, "IYYI." It occurs at regular intervals during the day and night in some locations. Some subway and "L" trains announce their approach by lights or bells in the next station. The sound you hear is caused by contacts under the track; when they operate by wheel pressure, the set picks up untuned waves from the sparks. Divide the number of clicks by four to find the number of coaches in the train. Some years ago, a person with deep imagination and shallow background stated that, as working range was proportional to wavelength, we could reach Mars by use of wavelength 30 million meters long. One reason for not sending a wave of that size on a stellar jump is that its frequency would be ten cycles per second; a bit low for radio frequencies, which do not become worthy of their name unless they oscillate at two or three thousand times that rate. Credit must be given, however, for the selection of a clear channel. That hum? It took the best equipment, in the hands of the best of the country's radio engineers, considerable time to locate the source. They traced it by directional aerials, rotating in two planes; they made phonographic recordings; they made careful logs of its times of appearance, and the point at which it struck. For a while it was quite common on many short wave bands. Because of its furtive, irregular raids into various channels, it was named The Shadow. Some thought it was intentional interference, radiated to hash up rival propaganda; others guessed it was the work of a crackpot scientist. As usual, other loose thinkers said it came from Mars. A serviceman might mistake it for "tunable hum." It was finally cornered and identified by the U. S. Navy. It came from diathermy apparatus. Hospitals use the machines to produce artificial fever in weak patients, so as to relieve heart strain which accompanies ordinary fever. The apparatus is, in receiver effect, a radio oscillator; it was found to be feeding energy back into power lines, which acted as radio transmitting antennas. The hum never disrupted communications, but the receiver buzz was plenty annoying; diathermy produced pyrexia, not only in patients, but in many short wave listeners. Means of suppression have been found. Some thought was given to the allocation of a frequency band for medical use, but, because the wave varies according to the doctor's adjustment and the size of the patient, other means of elimination were used. Occasionally, one gets on the air even now. It can be identified by its similarity to ordinary 60-cycle hum; unlike it, it is sharply tuned. "Tuneable hum" occurs in one definite spot; diathermy hum wanders about the scale. If you come across it some night, you can either tune it out or sit back and listen to what is probably a broadcast of a bad case of rheumatism. The essential question concerning our raising Mars boils down to "How far advanced is Martian intelligence?" not "Is there life on Mars?" When one considers the myriad of life forms on earth which exist under adverse conditions of temperature and pressure, it is logical to suppose life can be instilled into groups of matter other than those of the human combination. There is no reason to suppose other cellular compositions are not viable only because they are remote. There's a common noise from the set - a Brrrp, brrrp, with alternate noises alike. It isn't Mars, though; it's the flashing sign in the tailor shop across the street. Look out the window while you listen to the speaker; the sound comes each time the light goes on and off. One way to get rid of it is to speak pleasantly to the shop owner, asking him to remove the gadget. If he won't tune it out with a brick. Wishful thinking and late hours over a receiver have made many listeners jump up from their chairs when they heard such noises. The jumping motion is well known. You have heard of cosmic "raise," haven't you? Here's a peculiar sound. It isn't a planet, either, but I'll bet many set owners who stumbled on it wondered about it. A picture is being sent by radio. It might be from Berlin, Buenos Aires, New York, or London; they all have photo radio transmitters. The variations are caused by the scanning equipment, as it follows variations in picture density. The photograph revolves, and, as adjoining lines of the subject are sent out, it sounds like a man tearing one starched collar after another. You hear them most frequently following a disaster or putsch, when news agencies cannot wait for the material to arrive by ship. I'm beginning to doubt if we'll ever hear Mars. If they are less civilized than we, they can't; if more civilized, they probably don't want to. Hear that station, on voice? The speaker seems to be talking through a pillow. No chance of understanding it - the distortion is intentional. If it was Mars, they would call more distinctly. It happens to be trans-oceanic telephony, jumbled for secrecy. A person who goes hunting for Mars must know how to exclude a great number of such sounds. First, there is the huge group of all radio transmitters, damped and undamped. Their number is terrific, and includes all equipment designed for one- or two-way communication - all forms of voice, code, and the numerous intermediate forms; television, for instance. Then there is another huge group of noise sources that are not intended by design to give out waves which affect your receiver. For example, the purpose of a doorbell isn't to disrupt reception, but it does so while performing its intended function. The static coming from a doorbell, like a street-cleaner's interest in horses, is secondary. Both, however, exist. These forms of interference must be checked by the listener before he calls his local newspaper and announces that Mars finally has burst through our Heaviside layer. They fall into three general classifications: Man-Made Static Trolleys Shocking Machines Motors, malted milk drive Oil Burners Woman-Made Static Curling Irons Vacuum Cleaners Juice Extractors Violet Ray Machines Asexual Static Snow Hail Microphonic Tubes Lightning There are thousands of other unearthly sounds with no earthly purpose, but we are too close to the 30 to list them. Let's give up for the night. If Mars has been waiting for centuries another week or so will make little difference. Of course, if we really wanted to establish interplanetary communication, we could use light. We are positive light rays get across both ways, but we're not so sure about radio. Radio is lots of fun, though. [Jorgen Hals, mentioned in the second paragraph, observed the 4 minute, 20 second delay in a radio signal during tests in Oslo, Norway, on 31 meters. He reported his observations of the phenomenon on February 2, 1929. Mention of it was made in Proc., I. R. E., October, 1929, page 1750. In the third paragraph mention is made of a French Academy award for inter-planetary communication with any heavenly body except Mars. This was derived from an article in the May, 1938, issue of Coronet, titled "The Strangest Prize." It concerned the peculiar conditions of Mme. Guzman's will, which offered the money to the Academy for use as the specified prize; and the embarrassing position the members of the Academy since then while they tried to decide whether or not to accept the money and post the award. The U. S. Naval Research Lab report mentioned in paragraph 4 was published in the Proc., I. R. E., in October, 1929, in a paper "Ionization of the Atmosphere of Mars" by E. O. Hulburt. Part of the information concerning "The Shadow" was taken from RCA publicity on March, 1936, and December, 1935. The MS. was passed by that company's Department of Information on April 28, 1938. - Ed.]

Posted January 3, 2022 |

||