"Inventors of Radio" Professor A. E. Dolbear |

|

I have to confess that I do not recall having heard of Professor Amos Emerson Dolbear (aka A.E. Dolbear) prior to seeing this "Inventors of Radio" piece in a 1959 issue of Radio−Electronics magazine. Per the article, "In 1882, just 10 years after Loomis' patent was granted, Prof. Amos E. Dolbear demonstrated what he called an electrostatic telephone before the Society of Telegraph Engineers and Electricians meeting in London, England. This occasion - March 23, 1882 - was probably the first time the human voice was transmitted by radio." Prof. Dolbear was a contemporary of other early electrical communications pioneers like Alexander Graham Bell and Guglielmo Marconi. "Inventors of Radio" Prof. A. E. Dolbear

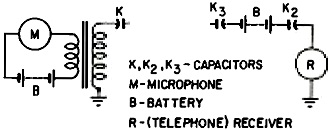

By Eric Leslie Our April issue told of an American, Dr. Mahloon Loomis, who demonstrated a system of communications by electromagnetic waves before Marconi was born. In 1882, just 10 years after Loomis' patent was granted, Prof. Amos E. Dolbear demonstrated what he called an electrostatic telephone before the Society of Telegraph Engineers and Electricians meeting in London, England. This occasion - March 23, 1882 - was probably the first time the human voice was transmitted by radio. Professor Dolbear (Tufts College, Boston, Mass.) was a distinguished researcher in a number of fields of physics. His microphones and electro-static telephone system were considered by many superior to Bell's. He also developed a number of instruments and classroom demonstrations, and investigated so many subjects that it was stated that a scientist pioneering in almost, any field would be likely to find that Dolbear had already written something on the subject. Although Dolbear considered it electrostatic, there is little doubt that his device would be defined as an induction telephone today. It consisted of an induction coil with a battery and microphone inserted in the primary. One end of the secondary was grounded, the other attached to a large elevated capacitor. According to Dolbear's explanation, a charge on the metal plate of a capacitor induces a charge of opposite sign on one placed near it. Therefore, another large elevated plate was used as the collector or antenna of his receiver. The battery in the receiving equipment demonstrates Dolbear's belief in difference of potential between ground and elevated point, and was apparently intended to serve a similar purpose as the modern "bias battery." Probably it was of some use, acting as a chemical rectifier of radio-frequency currents. The range, as demonstrated in 1882, was only a few feet, from one room to another. In 1883, Dolbear appears to have broken through into true radio without fully realizing it. He told the American Association for the Advancement of Science, "Louder and better results were obtained by using an induction coil having an automatic break interrupter and with a Morse key in the primary circuit, one terminal of the secondary grounded, the other in free air, or in a condenser for considerable capacity. At times I have employed a gilt kite, carrying a fine wire from the secondary coil. The discharges are then apparently nearly as strong as if there was an ordinary circuit."*

Dolbear's transmitting and receiving circuits. This equipment, installed at the Electrical Exhibition in Philadelphia, produced signals that could be received in any part of the large building and immediate neighborhood. In other experiments, he claimed a range of 13 miles, not an unreasonable figure for spark telegraphy with his crude apparatus. Though he was transmitting with true radio waves and no longer was depending on the capacitance effect of his "condensers," he apparently never suspected that fact, and always explained his results as a capacitance effect. It is not quite clear why Dolbear made no attempt to commercialize his telegraph. Possibly his electrostatic theory, which would have made him pessimistic as to the maximum range of the equipment, and the poor receiving apparatus, may have been among the causes. At any rate, he considered his inventions important enough to patent (US Patents 350,299 and 355,149) and he had in 1883 a wireless transmitter equal to and almost identical with that which Marconi demonstrated in 1896. * Hawks, Ellison, Pioneers of Wireless, page 135.

Posted July 15, 2022 |

|

Prof. A. E. Dolbear [1837-1916]

Prof. A. E. Dolbear [1837-1916]