First Phone Broadcast

|

|

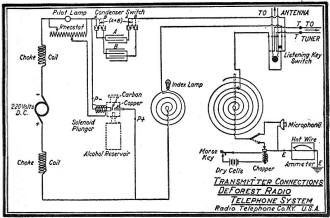

After having read many articles about Dr. Lee de Forest, it seems the poor guy was besieged his entire life by envious and/or belligerent electronic communications compatriots who sought to defame him and/or deny him of monetary rewards. This January 1947 issue of Radio-Craft magazine includes a dozen or so pieces written by friends and colleagues who recognized the momentous struggles and achievements of Dr. de Forest. Such burdens of fame are borne by many - if not all - persons of similar celebrity. Dogged persistence is the order of the day for experimenters and breakers-through of assumedly impenetrable walls. Guys like de Forest lived by the old adage recommending that "if at first you don't succeed, try, try again." You'll be amazed at how de Forest whipped - almost literally - that thing which was preventing his wireless telephone from working. BTW, as I've pointed out before, you will find the good doctor's last name written as "de Forest, DeForest, and De Forest." As evidenced by his signature on the magazine cover, "de Forest" is correct. First Phone Broadcast By Frank E. Butler The invention of the three-element vacuum tube by Dr. Lee de Forest in 1906-7 met with foggy and apathetic recognition instead of being welcomed with open arms and appreciated by the electrical industry and the government. The U. S. Navy Department flatly rejected the first Audion tube receiver as being impractical and unreliable. A storage battery, officials said, was subject to constant recharge with subsequent possibility of losing part of an incoming message; battery fluid might spill during action at sea, thus ruining the deck of the operator's cabin. Be-sides, it was too high in initial price and the renewal cost of bulbs, compared to the "low cost and reliability of detectors then in use. The Western Union and Postal Telegraph Companies, likewise the Bell Telephone System, frowned upon the idea. Long distance telephony, though greatly desired, was then unborn because mechanical relays were insufficient for the assigned task of boosting. Western Electric was concerned only in making instruments for the telephone company. George Westinghouse was interested in manufacturing air-brakes for railroad trains; Thomas Edison and the Victor Talking Machine Company in turning out phonographs. The General Electric Company specialized in motors, dynamos, and other small electrical parts. None of them were professionally interested in de Forest's idle dreams of a new wireless world - and all this happened 12 years before the Radio Corporation of America was thought of. Schematic of de Forest radiophone, the commercial version of the original transmitter. Courtesy Clark Historical Library Early de Forest radiophone equipment, type B arc transmitter and radio receiver. In a word there was no place nor persons to turn to for counsel, encouragement, or assistance. de Forest, far from discouraged; loomed up at the lab with a changed mental attitude, fresh for another round, and indicated that the fight was not over. His first suggestion was to chuck the wireless receiver under the table. He was through with it for awhile. He announced that his new idea was to develop a wireless telephone, and explained that this thought had been in his mind for some time while he was busy with other matters. Fortunately, the Parker-Building in New York City, had both 110 and 220 volts d.c. It was this latter voltage de Forest chose for experiment with a "singing arc." Among his first tests he found that the standard wireless telegraph transmission circuit was not adaptable to the arc principle, therefore the entire circuit had to be revamped and tested before it could function as a generator of the continuous, undamped, high-frequency waves which were required. Many experiments were conducted to determine the correct method of surrounding the arc with a gaseous atmosphere and the proper kinds of electrodes to employ. An alcohol lamp was decided upon to supply the required gas from denatured fumes within a chimney made of thin fire-clay through which two electrodes extended. These were located above or within the hot alcohol flame, in a chimney area about 1 1/2-inches in diameter. The chimney was open at the top and the strong, obnoxious odors emanating from the lamp were almost unbearable. It should be borne in mind that the Audion first was produced as a reception device. At the time of the wireless telephone tests de Forest was unaware of the oscillating qualities of the tube and its capacity to act as a transmitter. Finally all was in readiness for the initial test of talking across the room. A discarded shipping box salvaged from a rug concern on a lower floor provided the workbench upon which rested our hopes, represented by a breadboard hookup of a jumbled mess of tubular cardboard boxes mounted with wires, an upright standard or rod holding a Blake carbon-button telephone transmitter, an alcohol lamp with chimney, and, other apparatus. On the opposite side of the room the one and only Audion receiver, "Old Granddad" - which had been retrieved from underneath the table - rested majestically on the drafting board, the only piece of real furniture in the lab. The distance of this historic test was less than ten feet. Dr. de Forest, coatless and in a serious mood, stood before the transmitter, breathing the foul fumes of burnt alcohol, carefully changing from one adjustment to the other as he spoke into the microphone, drawling monotonously: "One, two, three, four - Can you hear me?" On the other side of the room, with headphone pressed tightly to my ear I listened, as I too changed tuning adjustments. In my uncovered ear I could easily hear de Forest's voice, but the headphone on the other ear was unresponsive. Just then a connecting wire broke from its hurriedly twisted joint and fell at de Forest's feet. Stooping to pick it up, his face accidentally touched the metal frame of the telephone transmitter. He jerked away. and exclaimed: "That's hot! No wonder the thing won't work. Now, I know what's wrong - those granules in that carbon button are packed together. The phone circuit is shorted!" He picked up a screwdriver and as he resumed his singsong monologue, he struck the metal frame with the handle, saying: Photo reproduced from Modern Electrics, Oct. 1908 issue. This "Aerophone Tower" was erected by de Forest's Radio Telephone Co. in 1908, on the Terminal Building, 42nd Street and Park Avenue, New York City. Intended for use in telephone communication with ships, it was 125 feet high and supported an antenna of eight phosphor-bronze wires, which ran from the top of the mast down to the edge of the building's roof. "One, two"- bang! The blow instantly dislodged the carbon impaction and permitted the word "three" to go through his jumble of wires and leap the intervening gap of space between us, the "three" being clearly audible in the "headphone on my left ear. Space conquered by wireless telephony! At that moment, in the early summer of 1907, radio broadcasting was born! In the dazzling light of current achievements it is far more difficult to recapture the immediate simplicity and importance of this occasion than to rhapsodize on its measureless portents. Commonplace ideas today - worldwide radio communication, talking pictures, radio, and electronics - all were unborn. The problem then was to transmit the voice only a matter of inches. "Let's rig up an antenna from that 30-foot flagpole on the roof and send this stuff out over the air," said de Forest. "Guess we'd better try it with music, though. We'll save our words and let any listener guess who's doing it." I was sent out to find a second-hand talking machine and returned shortly with a used phonograph and a single record - one side of which was "The Anvil Chorus" from Il Trovatore. The Brooklyn Navy Yard was about four miles away. Just inside its Sands Street entrance stood a 150-foot pole, surmounted by a crossarm from which hung a dozen aerial wires leading into a one-room wireless shack at its base. This shack housed the Yard's first wireless telegraph station, which was equipped with a Slaby-Arco outfit of German design. At the time this wireless telephone test was being made by Dr. de Forest, three Navy operators were on duty at this station - G. S. Davis, George F. Smith, and Arthur F. Wallis. Young Davis was on watch at that historic moment. With headphones on his ears he was vainly trying to intercept and copy a wireless message from a ship at sea. The signals were coming in very faintly. Nervously he fidgeted about as he sat on the edge of his chair, leaning forward and straining to hear the scarcely audible signals which were badly chewed up by rifts of uncontrollable static. The other two stood near-by, unable to give any assistance. Finally, with patience exhausted, Davis exclaimed: "I wish there'd be something else on the air besides that damned static -!" His wish was granted sooner than he expected, for at that moment the whispering, spasmodic dots and dashes were unceremoniously interrupted by mysterious sounds that were unmistakingly those of a "blacksmith hammering blows on his anvil with a sledge." Davis turned pale. He thought for a wild moment that his receiver was haunted; he later explained. Before he could utter a word, strains of music followed - a continuing portion of "The Anvil Chorus" record now being reproduced by de Forest in the Parker Building. Disbelieving his senses, Davis was both scared and dumbfounded. No wireless operator had ever before heard musical sounds come through headphones. Frantically he called to his companions: "Hey, fellers! Listen! Come here quick! Music, yeah, music - plain! Come quick - it's angels I guess." "Aw you're nutty, Davis," exclaimed Wallis. "Here, gimme those phones." He snatched the headpiece from Davis's head. "Let me listen to whatever you're talking about!" "God! You're right!" exclaimed Wallis, his tone of ridicule changing to one of amazement as he listened intently. "I never heard of anything like that before. Of course it's music - but it can't be angels, because how'd they be playing the 'Anvil Chorus' in Heaven, and that's surely what that music is. Here Smith - you listen! What do you think?" Smith had been impatiently standing by, anxiously awaiting the chance to hear. He adjusted the phones to his ears just in time to hear the last few notes of music, and then a man's voice broke in and said. "One" - boom - "Two" - boom -"Three" - boom - "Four" - boom -as de Forest wielded the screwdriver against the Blake transmitter between words to dislodge its granules of fused carbon. Smith, startled because he mistook the thumping "booms" for something else, took off the headphones and said to Davis and Wallis excitedly: "I heard something too, but it wasn't angels singing or blacksmith's pounding. What I heard was gunfire. It sounded like an admiral's salute, only there weren't that many shots. All I heard was four. I know I heard a man count 'em just before each shot." The three operators, impressed with the uncanniness of hearing mysterious music and voices coming through space by wireless; telephoned to New York newspapers and told of their experience. Stories were published around which reporters wove mystery as to through whom, where, and how such a new kind of wireless had come into being. As a result of this publicity the Literary Digest wanted a special story of the invention. A reporter and photographer called for particulars. de Forest gave them the details and they prepared to take a photograph of all the apparatus, including the original audion and its seven-plate Witherbee storage battery as well as the recently assembled wireless telephone transmitter which was now encased in a mahogany cabinet on top of which was the alcohol lamp. At the moment when all was in readiness for the camera shot I came in the door, just as the reporter said: "I think if one of you men stood in front of these instruments it would be more appropriate and descriptive of what it is." "Go ahead, Frank," said de Forest promptly, "You stand up in front of them - you've got your coat on." Doubtless he did not realize at the time the tremendous historic importance that photograph would one day assume, else he instead would justly and rightfully have stepped up in my place even though he was coatless. As it was, that picture - herewith reproduced - appeared in the June 15, 1907, issue of the Literary Digest. A few months afterward a disastrous fire destroyed the Parker Building, completely consuming all of de Forest's possessions, including his priceless records, and all the original audions and wireless telephone apparatus. Thus this picture represents the only physical evidence in existence of that basic equipment from whence grew radio broadcasting and all forms of electronic speech.

Posted April 22, 2021 |

|