In the Days of Spark - A Rescue at Sea

|

|

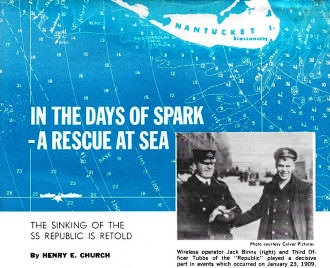

When you think about wireless (radio) saving the day for reporting trouble at sea, most of us (including, until now, me) think of the RMS Titanic incident that occurred on 14 April, 1912. Her telegraph operator, Jack Phillips, managed to get off an SOS (actually "CQD" in the day) message that was picked up by the ship Carpathia. In fact, this story of the SS Republic recounts events on January 23, 1909 when the good ship collided with Italy's Florida. Radio operator Jack Binns managed to get off a CQD message using backup batteries once he discovered the ship's power had gone down. Jack Phillips had the dubious honor of gaining celebrity for his heroic action a few year after Jack Binns. If I were the owner of ocean-faring vessels in those times, I would be sure to always hire radio operators named Jack! Mr. Binns wrote the foreword to Allen Chapman's series of "The Radio Boys" books from the 1920s. RF Cafe visitor Marek Klemes says, "With so many of them called Jack, I thought of new twist on the old saying 'Jack-of-All-Trades...' A wireless operator is a 'Trade-of-all-Jacks.'" In the Days of Spark - A Rescue at Sea Photo courtesy Culver Pictures Wireless operator Jack Binns (right) and Third Officer Tubbs of the "Republic" played a decisive part in events which occurred on January 23, 1909. The Sinking of the SS Republic is Retold By Henry E. Church Around the turn of the century, radio was generally considered a "new-fangled" invention by the few people who had even heard of it. Still fewer people displayed an active interest in radio - which was then called wireless. Nevertheless, its value was not overlooked by safety-conscious people in the marine industry and the various radio pioneers. Behind the scenes, powerful transmitting stations were built in strategic locations on the shore, and more and more ships were outfitted with transmitting and receiving equipment. But, more than any other single event in its short history, an accident which occurred in the early hours of January 23, 1909, dramatically shaped radio's destiny and enlightened the world to its existence and potential. The American-owned White Star liner, Republic, under the command of Captain Inman Sealby, departed from New York City in the late afternoon of January 22 bound for Gibraltar. Shortly after clearing Sandy Hook, she was enveloped in a blanket of fog, and the automatic fog horn was switched on. Jack Binns, the only radio operator aboard, busied himself with routine traffic. At midnight, after switching off his radio equipment, Binns retired to his cabin for a few hours of sleep. Meanwhile, at the Siasconsett wireless station on Nantucket Island, Jack Irwin had just relieved Jack Cowden for the midnight to 8 a.m. watch. The Republic was the only ship in transmitting range at the time. Later, still early in his watch, Irwin exchanged messages with the La Tourraine and the Baltic as they came into range. He knew the Republic had only one operator aboard who would most likely be in his bunk, so he settled down with a book to wait the night out. No other ships were due within range before dawn. At the same time, through thick fog and darkness, the Italian liner Florida steamed toward New York Harbor with her cabins filled to capacity with immigrants, refugees of a Messina earthquake. No radio was aboard, and Captain Angelo Ruspini was unaware that his ship was on a collision course with the Republic. When Captain Sealby heard an approaching fog horn, he ordered the Republic's engines shut down. Jack Binns was awakened from his light sleep (by the absence of engine noise), and suddenly the sound of tortured metal filled the air, followed by a jarring shudder which sent Binns sprawling to the deck. Regaining his footing, he rushed to the radio cabin only to find it badly damaged. He closed the transmitter key. The spark was there! But the ship's main electric generator ground to a halt before Binns could get a message out. Switching to storage batteries, he was concerned that his sending range was now reduced to between 50 and 60 miles, but his fingers began tapping out CQD (the SOS call-sign of the day). The Florida, which had sustained a crushed bow but apparently was still afloat, drifted back into the fog. At Siasconsett, Jack Irwin was dozing when the early morning cold brought him abruptly to wakefulness. A few minutes later he heard a weak CQD, followed by MKC - the Republic's call-sign. He answered immediately. With radio contact established, Binns reported that the Republic was sinking rapidly 26 miles southwest of Nantucket. Irwin acknowledged the message and asked Binns to remain at his post until help could be summoned. After answering Irwin's general call from the powerful Siasconsett transmitter, the La Tourraine and the Baltic changed course and headed for the stricken ship. The nearest of the two, the Baltic, was 64 miles from the Republic, and her top speed of 22 knots compounded with the fog made rescue seem impossible. The Republic, drifting hopelessly and now sinking about a foot an hour, drifted close to the Florida. Two anxious hours were spent by both crews as they transferred the passengers from the Republic to the smaller ship. There was much concern because the damaged Florida became dangerously overloaded. By noon, on January 23, Binns judged the Baltic to be within ten miles of the Republic by the strength of her radio signals. The rescue ship, running in soupy fog, had to reduce speed to prevent running into the Republic, and signal bombs were decided upon for final guidance. By 6 p.m., the last of the Republic's bombs was detonated, but it went unheard by the would-be rescuers. Only one bomb remained on the Baltic. Radio communication permitted the chronometers on the Baltic and the Republic to be synchronized. On the sinking ship, the quartermaster stood ready to give the signal the instant the last bomb was detonated. His arm fell and 45 crewmen, including Binns who had been called away from his radio, strained their ears to hear the explosion. About five seconds later, Binns, whose long hours of listening to weak and fading signals had sharpened his hearing, and Third Officer Tubbs, standing beside him, thought they heard a muffled sound. Taking a chance, Binns rushed to the radio cabin to give instructions to the rescue ship based on the bearing estimated by himself and the Third Officer. About 15 minutes later, the Baltic came into sight and hove to beside the sharply canted deck of the Republic. With the exception of Captain Sealby and Second Officer Williams, the Republic's crew was transferred to the Baltic. The Florida was located shortly afterward, and in rain, darkness, and heavy sea swells, the Republic's passengers were taken aboard the Baltic without loss of life. Only three passengers and two crewmen from the ships involved in the collision had been killed, crushed by the initial impact. As the dawn of January 24 crept into the sky and the rain which cleared the fog away ceased, a veritable armada of ships stood by to give assistance, The Baltic, with the limping Florida and several other ships in her wake, set out for New York harbor. The rescue had been accomplished against almost insurmountable odds. A last attempt was made to save the Republic by towing her to the shallows off Nantucket Island. This operation was doomed to failure because of the large volume of water weighing her down and adverse currents in the area. She disappeared into the murky waters before reaching her destination. Captain Sealby and Second officer Williams were rescued as the ship went down. The role that radio played in this rescue was publicized around the world, and Jack Binns stepped ashore to find himself a hero. He later became, successively, flying and radio instructor for the Canadian Flying Corps and Radio Editor for the New York Tribune. Siasconsett grew to become one of the most important radio stations on the Atlantic seaboard. Among its distinguished alumni of operators is David Sarnoff, now a brigadier general and Chairman of the Board for the Radio Corporation of America. The rescue of January 23-24, 1909, may sound like a work of fiction, but what might the outcome have been if neither the Republic nor the Florida had radio facilities? Or if the collision had occurred a few short months earlier, before the Republic was equipped with radio? The collision (similar to that of the Andrea Doria and Stockholm some 47 years later) might have gone down in history as one of the great maritime disasters of our time.

Posted June 12, 2023 |

|