Operation Telephone 1965

|

|

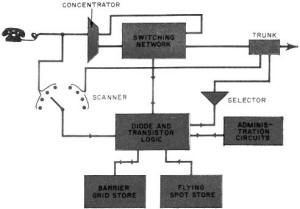

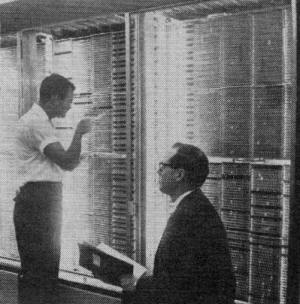

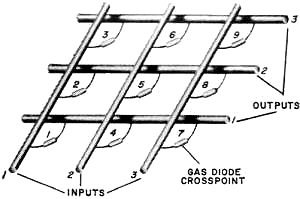

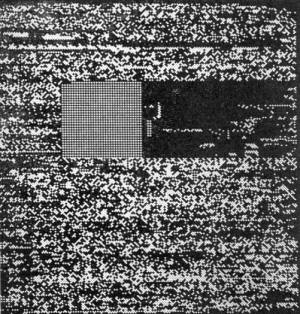

Call forwarding, call waiting, call holding, speed dialing, conference calling, all of these features are taken for granted with mobile phone and VOIP phone service and are included in the base service package. It will cost you extra if you subscribe to a local legacy POTS (Plain Old Telephone Service) provider. What is standard now was considered ground-breaking technology in the early1960s when this article appeared in Popular Electronics magazine. When phone calls were processed via human operators manipulating patch cords and then electromechanical relays, it was enough to simply place a successful call and not be interrupted or disconnected. Once transistorized circuits entered the scene, much more was possible, and phone system engineers were quick to exploit the technology. Sophisticated decision making requires both logical circuits and a form of memory. Logic could be provided using hard-wired diode steering, but a fast and efficient means of storage was needed that did not involve vacuum tubes. That is where the photo-optic based "flying spot store" came in. It "wrote" digital data onto a strip of film that was scanned by a light beam to read back information. Operation Telephone 1965 Within the next four years, American's telephones will undergo a major and far-reaching innovation when the new, all-electronic "centrals" take over. By Ken Gilmore The time: a day in 1965. You're planning to spend the afternoon at a friend's house. But you're also expecting an important telephone call. You pick up your phone, dial first a special code number, then your friend's number. This done, you leave for his house, knowing that all calls to your number will be automatically switched to his. When you return home that evening, you dial another code number and incoming calls are once again routed to your own phone. This special service - and dozens of others just as advanced - will soon be available to you. Already, a prototype all-electronic telephone central office is in operation in Morris, Illinois. And it's delighting subscribers with services which make present-day systems seem as obsolete as a hand-crank on an old-fashioned wall telephone. Special Services. Within a few years - as versatile all-electronic equipment replaces the present relay-switching systems - your phone will perform such tricks as these: - You're talking to a friend about a new stereo amplifier you're planning to buy. But you need more information. So without either of you hanging up, you simply dial your dealer's number. A few seconds later he is connected into the circuit, and all three of you can discuss the amplifier at will. You can even continue calling additional numbers - as many as you like - and all will be connected so that everybody can talk to everyone else. Control center (three photos, above) of world's first all-electronic telephone central office, now serving customers in Morris. Illinois, is but a portion of overall network shown in block form below. The system was developed by Bell Telephone Laboratories. - There are several numbers you call regularly. A word to the central office, and each of these "regulars" is assigned a special two-number code. Then, instead of having to dial the usual seven-digit number each time, you simply dial "12" when you want your office, "13" for the corner drugstore, "14" for a friend you call often, and so on. - You run a small business and don't want to miss any incoming calls. You make the proper arrangements, and if your office line is busy when someone dials it, your home phone rings automatically. If your home phone is busy, too, a third number - perhaps an answering service - will ring, and so on for as many alternate numbers as you wish. These are just a few of the scores of special services you'll enjoy when electronics takes over completely. With the new system, switching and routing of calls - now done by relatively slow-moving relays - will be accomplished with no moving parts at all. Hordes of electrons rushing through transistors, diodes, and gas tubes will do the job, and they'll do it within millionths of a second. Thus, the all-electronic system will be able to perform thousands of different operations, carrying out extremely complex switching operations impossible with present equipment. Electronic "Central." To see how the new system works, let's take a look at what will happen to the central office - the heart of any telephone system. At this giant terminal, the wires from your phone, thousands of others in your area, and trunk lines from communities all over the country are brought together. The sole purpose of all the complicated gear at the office is to connect the line from your phone to that of any other phone you want to reach. In the old days, this was a simple job. An operator simply took a plug connected to your line and pushed it into a jack, connecting you with the number you wanted. Then she pressed down a lever to ring the bell. A few years later, the dial system came along and substituted automatic relays for the plugs. Every time your dial clicks, a number of relays move. When you have finished dialing, the clicking relays have selected a single phone and connected your line to it. In the new electronic system, a giant computer with a special scanner checks over every line coming into the central office to see whether it is in use. It does this job so quickly that it takes just one-tenth of a second to check all of the thousands of lines terminated at the central office. As soon as one check is over, it starts another. Thus, every line is checked to see whether it is idle or busy ten times every second, twenty-four hours a day. Scanner-Computer Circuit. Most of the time any given line will be idle - the phone will be "on the hook." But when you pick up your telephone to make a call, the scanner notices not more than one-tenth of a second later that your phone is no longer idle, and notifies the computer. In the next few millionths of a second, this electronic brain performs a complex series of operations. First, it checks its memory to see if a change was made when you picked up your telephone. It finds that there is no record of your phone having been in use a tenth of a second before. It then checks to see if your line is ringing. If it is, your picking up the phone would be in answer to the ring. If there is no ringing, the system concludes that you picked up the phone because you want to make a call. Having reached this conclusion, the computer switches the dial tone onto your line to notify you that it is ready for you to dial. At the same time, it writes your phone number on what engineers call "an electronic scratch pad" - a temporary memory circuit. It also reserves a space on the "scratch pad" to record the number you dial. Finally, it steps up the number of times your line is being scanned from the regular 10 per second to 100 per second, so that it won't miss any of the pulses your dial sends out as it clicks around. All this began when you lifted the phone from its cradle, and was completed long before you got it to your ear. In addition, the scanner went on sampling several thousand other lines, and signaling the computer to take whatever action was necessary in each case. In this way, one scanner-computer circuit operates fast enough to handle all the business on all of the lines coming into the central office, moving from one to the other with lightning speed. As you dial, the scanner is looking at your line 100 times a second. Every time your dial generates a pulse, the scanner notes the event and records it in its temporary memory. When you finish dialing, the computer hooks a ringing connection to the line you dialed. It also sets up the ringing connection on your line, to assure you the line you want is being rung. Simultaneously, of course, the scanner is checking the line you're calling. When someone answers, the "brain" is notified, and it then sets up a talking circuit between the two lines. After your conversation, you hang up. The scanner notes that your line is now idle, but just to make sure, it waits until your line reads idle for three consecutive checks. Satisfied that you are now through talking, the computer disconnects both phones. Automatic Switching. Why set up such a complex electronic system when the present-day relays seem to do the job pretty well? There are several reasons, but by far the most important is the fact that the electronic "central" can do things no other setup can even approach. When diode fires, the neon glows, setting up a low-resistance path from cathode to anode. Switching network in the all-electronic telephone system uses tiny gas diodes in place of conventional relays to connect one line to another. Network of wires can easily be connected by means of diodes. As long as diodes do not fire, wires are not connected. But if diode 3 fires, for example, input 1 and output 3 are connected; if diode 4 fires, input 2 is connected to output 1. Cathode-ray tube in electronic central's "flying spot store" is a photographic "memory" device capable of storing over two million "bits" of information. Tube sweeps spots on film - over 30,000 to each 1 1/2" square - which are either clear or opaque and which pass or withhold the beam of light accordingly. The present relay system can be connected so that another phone will ring when your line is busy. But to do this, the phone company has to wire in separate circuits, including special relays at the central office. Once the circuit is in, it is permanent. And since extra labor and equipment are involved, it is relatively expensive. With the electronic system, no wiring changes at all are required. The computer which controls the system has memory circuits. Instruct it to ring another phone when your phone is busy, and it complies without so much as a single wiring change. Other arrangements which are now completely impossible will be a snap with the electronic system. For example, our present setup cannot let you reach regularly called numbers by dialing only two digits instead of the usual seven. But the computer finds this chore simple. And since the electronic giant acts with such tremendous speed, it can take care of thousands of such special requests without interrupting its normal service. The new system even diagnoses its own troubles, and in some cases repairs them. If a certain circuit goes out of order, the computer automatically switches in a spare. Then it runs a number of checks on the bad unit, diagnoses the trouble, and writes instructions for replacing the faulty part on a teletype-writer. It also periodically checks some 800 critical voltages throughout the system and lists them on the teletype. If any voltages are off, technicians can cure the developing trouble before it becomes serious. The system's teletype, by the way, is a vehicle for two-way communications-technicians also use it for "talking" to the computer. Let's say, for example, that you want all incoming calls to your office switched to your home phone from five o'clock every afternoon to nine each morning. You simply call the telephone company, and an operator- using the teletype - "tells" the computer what you want. Your phone service is then automatically switched as you directed, without your having to worry about it again. If you move, technicians can use the teletype to instruct the computer to take your line out of service. Or they can call on it to add additional services to a particular telephone, run special checks, and so on. You can even ask the computer what time it is, and it will respond with the month, day, hour, and minute. Experimental Systems. The first experimental electronic "central" mentioned earlier went into regular commercial operation for the first time only a few months ago. But Bell Laboratories scientists actually began working toward such a system in the early 1930's. Even at that time, they saw that electronic switching would offer many advantages which could be achieved in no other way. Experimental systems were built and tested - and they worked. But they were not practical for regular use. In the first place, the number of vacuum tubes required for a full-scale system was enormous - and enormously expensive, since the tubes gobbled up a lot of power. Then, too, the power generated tremendous amounts of heat, and the heat created additional problems of its own. Furthermore, building a memory section for the computer would require millions of tubes. And with that many of the little bottles, reliability would become an overwhelmingly difficult problem. In use, it was calculated, tubes would "pop" faster than technicians could replace them. The first big breakthrough came in the late 1940's when Bell scientists invented the transistor. This solved the problem of the switching circuits, but a practical, inexpensive, large-scale memory was still not available. In 1954, Bell executives decided to launch a multi-million dollar research program to develop such a memory, and to incorporate it into a full-scale, practical electronic-switching system. Before the project was over, scientists assigned to it had designed and built two "memory" devices. One was for semi-permanent information which would be stored in the computer, such as a list of which telephones are connected to which lines. The other, with a "temporary" memory, "remembers" information the system must retain for only a few minutes, hours, or days - such as the number you are calling, or where you can be reached for the next few hours if you've left instructions for your call to be transferred. Future Possibilities. Although the electronic system now in operation in Illinois performs many unusual services, the range of possibilities has hardly been touched. When R. W. Ketchledge, director of Bell's electronic central office development project, was asked just what the system could do, he leaned back in his chair and smiled. "There's only one way we can answer that," he said. "And that's, 'What did you have in mind?'" He went on to explain that the computer can be instructed to make virtually any kind of interconnection you can dream up, and all without changing a single wiring connection. A couple of the possibilities Bell officials think might be popular with customers are: - The "Baby Sitter." Before you go out for the evening, you dial a special code, then the number where you can be reached. If the baby sitter needs you, she'll simply pick up the phone and wait for five seconds. The computer will recognize this as a special signal and ring the number you specified before you left. The service could, of course, be left in operation permanently for any number you call frequently . - The "Camp-On." You call a friend and his line is busy. You're anxious to reach him, but don't want to keep dialing his number over and over again. Besides, he might complete his call and dial another number before you get through. With the "camp-on" system in operation, a pleasant voice notifies you that his line is busy. But if you hang on, the voice says, the system will ring his line the instant he puts his phone down. So impressive is the operation of the prototype electronic "central" that officials are rushing plans to extend the system to the entire country. Since it takes a long time to standardize designs, set up production lines, and install these immensely complex systems, you won't have an all-electronic phone next month, or even next year. Officials hope, however, to have electronic central office equipment in normal operation in some places not later than 1965.

Posted December 24, 2021 |

|