Interference from Left Field |

|

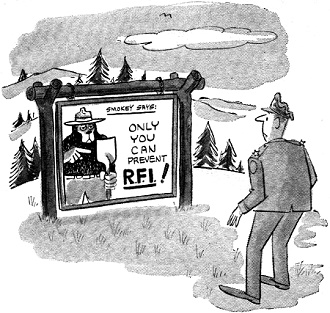

By 1970, the airwaves were really getting crowded. Lots of high power commercial and military gear was online, and the radio listening public was setting new record highs every year. As such, many new sources for radio interference were being discovered, and sometimes the problems caused went well beyond just a little noise being superimposed on top of Neil Diamond's newly released Cracklin' Rosie or the lads from Liverpool's The Long and Winding Road. Often, the interference was overwhelmingly annoying. The FCC was being flooded with complaints. Digital computers were creating a whole new type of electronic havoc, and leaky cable television cables and amplifiers caused all kinds of headaches to over-the-air sets. Rusty bolts and chain link fences in the vicinity of high power radio and TV towers - and even radar installations - manifested themselves as detectors by virtue of their nonlinear nature. I remember when people at Robins AFB, in Georgia, would sometimes complain to our radar shop because their radios would blip once every four seconds as the search radar antenna swept past their radios. There was also the time while working as an electrician in my pre-USAF days that I remember picking up a nearby AM station on my audible continuity tester while ohming out some cables in a roof-top air conditioner unit on commercial building I was wiring. Interference from Left Field by Edward ArnoldIn a south Florida town recently, a newcomer to the community complained that all she got on the "local" TV channels was interference; yet she received distant stations - more than 100 miles away - without trouble. Upon investigation, it was determined that a distribution amplifier for a local cable-TV (CATV) system was leaking signals right into the young lady's antenna. On the local channels, she received TV direct from the stations mixed with the signals from the amplifier. For distant stations on other channels, she received only the signals from the CATV amplifier and no local interference. In this day of super-power transmitters and super-sensitive receivers, incidents such as this are becoming too common, unfortunately, to even be reported. But what is worse is that now we're getting interference in the oddest and goofiest ways-you might call it interference from left field. The problem is simply that devices that weren't intended to be transmitters are transmitting and devices that weren't intended to be receivers are receiving all sorts of signals. Even Computers Are Culprits Who would ever have suspected, for instance, that a computer could act as a receiver? Yet one radar installation kept having its core memory erased for no apparent reason until someone noticed that a radar antenna nearby was swinging its beam toward the computer just when the cores were erased. And if a computer can act as a receiver, who's to say that it can't transmit also? At one telemetry station a while back, the operators kept getting garbled outputs until radio frequency interference (RFI) specialists determined that computer equipment at the station was radiating a signal that was being received by the station's huge telemetry dish! In this computer-happy world, we probably are in for a lot of such computer-generated interference; the square-wave signals in digital circuits have a wide range of harmonics. On the home side, of course, digital circuits are uncommon, but new devices like cable TV have their share of interference problems. CATV firms have found (the hard way) that 300-ohm twin-lead in a customer's house can radiate the CATV signals so they now require use of coaxial cable exclusively. That Old Bugaboo Corrosion. Whether on the home front, in industry, or in the military, we still get interference from an old enemy: corrosion in metal joints. The corrosion sometimes creates a non-linear resistor which acts as a mixer of electromagnetic signals. When the signals are very strong, the joint may even re-radiate the mixed signals. Typical of such occurrences is the case of the radio that would suddenly receive several stations at the same time when anyone walked across the floor. It was found that metal heating ducts in the floor had poor joints which acted as mixers and re-radiators when sufficient pressure was applied from above. Much the same thing happened to a Chicago engineer back in the days of trolley cars. As he was waiting in his car at a traffic light, a trolley car pulled up beside him; whereupon his car radio was overcome with cross-modulation. His theory was that the poor connection between the trolley wheels and the ground rail at that intersection created a nonlinear resistance. While such events are normally humorous and of no particular consequence, when they happen on board some of the U.S. Navy's ships loaded with tons of high-power transmitters and very sensitive receivers, they can be almost as dangerous as they are exasperating. Salt-water corrosion naturally is an everyday problem on ships, but if you have dozens of different antennas in a limited, crowded space, salt corrosion can create almost unbearable RFI. Although the re-radiated signals from the nonlinear joints or contacts may be too weak to be transmitted more than a few feet, on a ship it may take only a few feet to get into somebody else's receiver. Also, on ships, the abundant metal surfaces, chains, and doors sometimes are of a size or length that is related to the wavelength of high-power transmitters on board. More than one sailor has started to open a hatch only to find that the door is hot with RFI. A different kind of RFI problem for the military is predicted when the Nike X anti-ballistic missile weapon system goes into use, according to a story in "Electronic News" (March 25, 1968). The site radars for this ABM system threaten to knock out virtually all other radio communications in the vicinity. Hopefully most of us would not complain about this RFI since the site radars would be turned on only to direct missiles toward incoming warheads. Surely the most impatient TV viewers can tolerate TVI for such a good cause. To resolve RFI problems such as this, the Department of Defense has set up an Electromagnetic Compatibility Analysis Center. Its job is to tell the military specifically what types of interference they can expect if they change locations or shift frequencies. Enter the Forest Ranger If a military organization decides to run from its RFI problems and place its transmitter on a high mountain top on government land, it will have to discuss electronics with, of all people, the U.S. Forestry Service, probably the last group in the world you would expect to have an interference problem. The reason for their involvement, however, is quite simple: government land on mountains is often administered by the Service. Mountains obviously are just the place for line-of-sight microwave transmitters, etc. Put all those transmitters on a mountain top and you have a possible RFI problem! Or should we say an "EMC" problem? In keeping with the times, some engineers are now referring to RFI problems as electromagnetic compatibility (EMC) problems to give recognition to the fact that not all emanations are at radio frequencies but can occur throughout most of the spectrum. Regardless of the name, EMC problems do not often have easy (inexpensive, that is) solutions. To cure these problems requires proper circuit design as well as bonding, grounding, and shielding which can be expensive and often create their own problems. Bonding straps, for instance, may be resonant at certain frequencies and create their own RFI. We are bound to have problems with electromagnetic smog as long as, in the words (in "IEEE Transactions on EMC," October 1964) of Rexford Daniels, president of Interference Consultants, "we try to fit a microvolt civilization into a millivolt world."

Posted December 7, 2021 |

|