Hams Go Video

|

|

Ironically, an RF Cafe visitor just within the last couple days wrote about possibly getting his Amateur radio license in order to permit live broadcasting of his kite-borne video camera system (known as "Kite Aerial Video" [KAV]), or Kite Aerial Photography [KAP]). Slow scan television SSTV has long been a popular facet of Ham radio since prior to broadband Internet connections; it was the only practical method available. Older equipment was large, heavy, power hungry, and relatively expensive, but today you can buy a much improved camera for a few bucks that transmits real-time via an unlicensed 2.4 GHz wireless link. That data stream can be recorded for later use of streamed real-time to the Internet. As with so many other things, easy availability takes some of the challenge out of it, but the world benefits from having all kinds of way-cool videos to watch! Hams Go Video: Amateur TV - an exciting new hobby

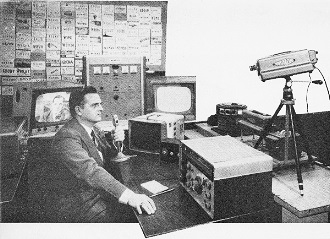

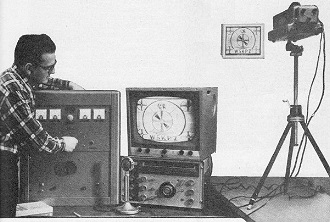

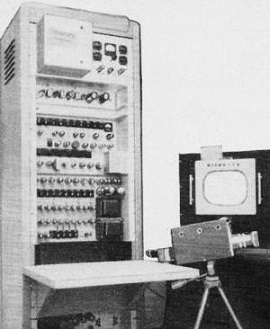

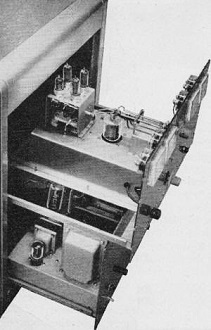

One day, in the not-too-distant future, the average ham may mean it literally when he asks a distant buddy, "How do you read me?" He will mean not "How well do you hear me?" but rather "How clearly can you read my test pattern?" Ham TV today is admittedly a limited pastime, indulged in by a handful of dedicated adventurers using makeshift equipment. But at least one electronics manufacturer, the Electron Corporation of Dallas, Texas, is determined that things will not always be thus. Mort Zimmerman, the company's president, reasoned that when the Federal Communications Commission set aside the 420-450 mc. band for amateur television back in 1957, it meant for the band to be used. So he is marketing a complete ham video station. Dave Baxter of Dallas, known in amateur circles as W5KPZ, is using the new equipment to telecast to several other Dallas amateurs whose TV sets are equipped with special u.h.f. converters to receive him. And in Denver, two ham clubs are buying the Electron Corp. gear on time, paying for it with a $6 monthly membership assessment. The cost of the complete package at present is $2895. TV ham Dave Baxter, W5KPZ.TV, is sandwiched between his gear. Dave works out of Dallas, Texas. Sophisticated version of flying spot scanner. Older system involves putting transparency directly against screen of TV set with raster reduced to size of transparency. Tuning up the transmitter. Dave Baxter's station is believed to be the first installation of commercially made (Electron Corp.) ham TV gear. Ham TV Pioneers. Though such commercial gear should do much to popularize ham TV, amateur television has been with us longer than you might think. Its roots can be traced to the earliest days of video experimentation. And just before World War II, the Radio Corporation of America actively encouraged amateurs to jump on the television bandwagon it was then striving to get on the road. With the war, television went into mothballs for five years. But when it ended, the Armed Forces unloaded tons of surplus radar and other electronic gear. Some of the Armed Forces' surplus gear was snapped up quickly by a few of the more enterprising radio amateurs. Many of these hams were operating on the West Coast, where probably the greatest concentration of video hobbyists can be found today. On clear, bright days, small groups of these intrepid pioneers can be seen climbing up neighboring mountains, loaded down with equipment with which to exchange test patterns and live images. For transmitters these hardy hams generally use modified radar gear, though some build their own. The pickup equipment is likely to be a primitive iconoscope camera originally built for wartime guided bombs, a Buck Rogers type weapon tried by the Army Air Forces toward the close of World War II. Unfortunately, these surplus iconoscope cameras provide considerably less than good picture quality, and they gobble up light much too greedily. So the average member of the tiny TV ham fraternity is more likely to content himself with transmitting slide shows. For this he uses a setup known as a flying spot scanner. Flying Spot Scanner. This interesting device is actually made up of two separate items: . an ordinary TV receiver and a photoelectric multiplier tube, such as the 931A. Together with a video amplifier and a video transmitter, the flying spot scanner makes a dandy gadget for televising still transparencies. Here's how it operates. The TV set is tuned to an unused channel, so that its screen is lit up with the swept trace lines but shows no picture. Its brightness control is turned up as far as possible. Next, a slide or other transparency is placed against the face of the picture tube, and the set is adjusted until the trace lines just fill the part of the tube covered by the slide. Now the photoelectric multiplier is placed right in front of the slide. The light hitting the photocell, after going through the transparency, is not just a blob of illumination; it is actually the scanning action of the picture tube's electron gun. As this light hits the photoelectric tube, it generates a signal that is fed to the video amplifier. The video amplifier, in turn, feeds either a monitor set, a video transmitter, or both. Result: a neat reproduction of the transparency on the monitor and on the receiving set of another ham. This technique can also be used to produce positive images with photographic negatives if their phase is reversed in the video amplifier. Home-built rig of Arnold Proner, broadcast engineer for NBC, includes rack-mounted amplifier-transmitter, vidicon camera, and monitor. Most of the equipment is similar to early commercial circuitry. Rack-mounted ham TV transmitter manufactured by Electron Corporation is small enough to sit atop a desk. Use of slides permits the equipment to be adjusted and serviced easily. Two Typical TV Hams. Many of today's television amateurs, as might be expected, are actually professional electronics engineers who like to tinker with video in their spare time. In New York, for example, two TV hams are Arnold Proner, W2OMU, a television broadcast engineer with the National Broadcasting Company. and Bill Ziner, W2MMY, an engineer in the research department of the Lewyt Corporation. Working together, Arnie and Bill actually built their own vidicon cameras and amplifier-transmitter gear from the ground up, copying standard circuits in commercial use. The cameras are patterned after an old RCA vidicon design used for televising motion picture films. For optics, Arnie Proner uses an f/1.9 50-mm. lens from a Leica camera. "It gives a slightly telephoto effect on the vidicon," he will tell you, "but it does a pretty good job." Before Bill Ziner graduated to the vidicon, he had worked out a really sweet version of the flying spot scanner. "I took an old 35-mm. projector and rewired it, replacing the lamp with a photoelectric multiplier tube," he relates. "So I had a perfect slide changer setup for my transparencies. Then I simply filled my entire TV picture tube with scanning lines and focused the slide projector on its face. I worked out the focus by the focal length of the projector's lens and checked it on the monitor. Airing slides with this rig was just like putting on a regular slide projection show, only the process was reversed." Vidicon Simplifies Matters. The vidicon cameras turned the flying spot scanner into a child's toy for Bill and Arnie. They still sent each other test patterns and other slides in transparency form, but now they were also sending live pickups with ease. And transmitting slides was a much easier project. They did it in two ways. Either they projected the slide on a wall and turned the vidicon camera on the projection or they aimed a slide projector right into the vidicon camera's lens. This would give a reverse image which was then corrected by electronic flopping in the amplifier. Arnie also succeeded in transmitting movies. He did this by beaming an 8-mm. projector on a screen made of translucent material and spotting the vidicon behind the screen. The vidicon picked up a reverse image from the rear of the screen, and the image was electronically flopped. Because their gear was not fully refined, Arnie and Bill found that they had to take turns transmitting to one another on video. Their transmitters completely blanked out their own receivers. But this was normal radio practice and presented no problem. Arnie's gear once was put to a very practical use when he and his wife couldn't corral a baby-sitter while they made a short visit next door. Arnie trained the vidicon on his sleeping infant and Bill did the baby-sitting electronically at a distance of ten miles. Commercial Equipment. Ham television is characteristically a strictly video proposition; because hams have radio transmitters and receivers anyway, there is no need for TV audio circuitry. And amateur TV, as practiced by these pioneers, is primarily a builder's hobby. There are few other video hams within reach of their short-range equipment, and the challenge is mainly one of seeing if they can put together workable rigs. However, the Electron Corporation, a subsidiary of Ling Electronics, Inc., hopes to change all that. Its new equipment is ready assembled, specially designed for operation on the 420-450 mc. amateur television band. Field tests by the company indicate that this equipment provides excellent reception at a distance of 18 miles. The possibilities of relay transmission are being explored too. With a relay system, a string of hams spaced 18 miles apart could establish a network to cover real distance. Electron Corp. officials are talking about the use of their equipment to bring amateur collegiate radio into the television picture as a non-commercial educational service. Another possibility they envision - and one linked with their hopes for college TV - is the purchase of converters and special antennas by the general public for looking in on ham television. The u.h.f. converter, incidentally, is price-tagged at $79.50, and the receiving antenna for it costs $12.50. Television may eventually become an important adjunct to the ham in his traditional emergency service role. Visual coverage of disasters could prove valuable in coordinating civil defense activities by adding "eyes" to the "ears" of emergency radio communications.

Kite Aerial Video

Posted February 2, 2022 |

|

By Art Zuckerman

By Art Zuckerman