Whatever Happened to Atwater Kent?

|

|

I have to admit that when presented with the Atwater Kent Award upon graduation from the University of Vermont in 1989, I had no idea who the fellow was. It wasn't until years later I read the name in IEEE's Spectrum magazine article (this one is from a 1969 issue of Popular Electronics) and learned he was a radio designer and manufacturer. In the course of publishing the RF Cafe website, Atwater Kent's name appears on occasion in Radio Data Service Sheets like this Model 776 in the June 1936 issue of Radio-Craft magazine. According to this article entitled "Whatever Happened to Atwater Kent?," that was the year he shut the doors of his extremely profitable business because he refused to give in to union thugs attempting to organize his employees. If you are not familiar with the history of Mr. Arthur Atwater Kent, then this story is one you will appreciate. He was one of the relatively few entrepreneurs who managed to thrive during the Great Depression years. Whatever Happened to Atwater Kent? World Renown ... Manufacturer of 5,000,000 Receivers ... Famous for Quality ... But He Closed the Doors and Walked Away By Frank Atlee, K4P1 Although more than 40 years have elapsed since the name Atwater Kent was a household word, the radio receivers he manufactured were so well made that thousands are still in existence and in operating condition. Many more Atwater Kent receivers are unearthed daily from cellars and attics to be restored by antique-radio collectors and made conversation pieces for modern living rooms. The story of this unusual man and his company in many ways parallels the heyday of mass production ascribed to the Ford Motor Company. At one time, Atwater Kent was a company known the world over and even the most conservative estimate of its manufacturing facilities indicates that it produced well over 5,000,000 radio receivers. The Atwater Kent Company was a well-established manufacturing business nearly 20 years before the first radio broadcast. Starting with the making of voltmeters for telephone linemen, the company gradually expanded to include the manufacture of ignition systems, starters and generators for pre -World War I automobiles. Residing on the "Main Line," then the home of many wealthy Philadelphians able to purchase the fine cars of the day, Kent observed that ignition systems and electric starters (if any) were usually under-designed and subject to frequent failures. Kent purchased several dozen used cars on which to work toward developing improved electrical systems. In a short time, he had invented the "Unisparker" and in 1914 received a medal from the Franklin Institute of Philadelphia. He also developed his type "LA" ignition system for the Model T Ford. Having worked closely with 4- and 6-cylinder engines, Kent predicted that eventually the 4-cylinder engine would be a thing of the past. First Expansion

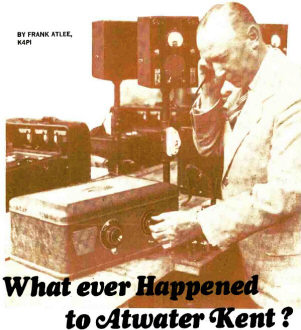

The A -K Model 37 was a 7 -tube a.c. operated receiver with the popular 2 r.f., detector, 2 audio circuit. Model 10 was next to the top of the A -K line in 1923 selling for $80. Open breadboard design with the connecting wires hidden under the fine wooden finish was a particular trademark of A -K. Speaker in background is from another A -K era around 1927 when Kent recognized the importance of selling loudspeakers. (Author's collection)

Kent followed the Henry Ford thinking and manufactured receivers on an assembly line. Factory conditions were better than most companies of the day. This is a corner of the author's fine collection of Atwater -Kent and other antique radio receivers, microphones and keys of 1920-25. Author worked at the A-K factory. Some Highlights in the Atwater Kent History In late 1926, Atwater Kent announced that he had manufactured his one millionth a.c. operated radio receiver. The original of this receiver was allegedly donated to the then King of Spain. However, a sufficient number of these sets (the Model 35) all in a gold-plated finish and all with serial numbers starting at 1,000, 000 were shipped to his wholesalers for display. In 1927, Kent was visited by Helen Keller and her companion. Miss Keller was personally conducted on a tour of the plant and was presented with a special radio receiver and magnetic cone speaker. By pressing her fingers lightly on the speaker cone she was able to enjoy music through the delicate vibrations of the cone. In the next year, the famous Russian inventor, Leon Theremin, visited the Kent factory with the intention of selling the patent rights to the manufacture of his electrical musical instrument. A working model of the Theremin was in the Atwater Kent laboratories for several months when it was finally decided that the instrument was too much of a novelty. A year later, RCA bought the patent rights, but at a selling price of $300 per Theremin, the project was a financial failure and gladly forgotten. In August, 1928, the two millionth radio receiver was given to Mrs. Thomas A. Edison. Atwater Kent, the Philanthropist Always very publicity conscious, Kent's most notable contribution was in promoting the public's interest in music. In particular, he sponsored opera broadcasts on the radio networks. The first of these broadcasts was in October, 1925. In addition, Kent supported local schools of music in Philadelphia and provided scholar- -ships in music to promising local singers, including Philadelphia's Wilbur Evans, who later became nationally famous. Through his original connections with New England, he contributed liberally to the Perkins School for the Blind; and, toward the end of the manufacturing period for battery-operated radio receivers, he ordered the donation of a large quantity of these receivers to the merchant fishing fleet sailing out of Boston Harbor. Another step taken by Atwater Kent to prevent his name from becoming forgotten was the establishment of the Atwater Kent museum in a small building on South 6th Street in downtown Philadelphia, not far from his original place of business. The museum does not display his manufactured products but is devoted primarily to historical items of Philadelphia. His many philanthropic and charitable contributions were not tax deductible since there was no applicable income tax in those days. Considering that the Atwater Kent Manufacturing Company, Inc. was owned and controlled by Mr. Kent himself, with only one other minority stockholder, one can scarcely imagine the profits that were made during the free-spending boom years of 1924-1929. Sensing that the market for his automotive products was rapidly expanding, in 1914 Kent purchased a large tract of ground north of the Wayne Junction branch of the Reading Railroad in Germantown, Philadelphia. As soon as this factory was completed, he partially switched over production during World War I to the manufacture of gun sights. Kent's long-range plans for the postwar economic boom did not materialize and in 1920-21 Kent found himself in a temporary business depression. Scouting around with his usual keen vision for products to manufacture, he decided to look into the new craze of radio broadcast listening. Kent hired two well-known Philadelphia radio engineers and from a modest start in making transformers he rapidly branched out into the manufacture of tuning units, detectors, and one- to three-tube amplifiers. Kent even assembled a five-tube radio receiver with all transformers sealed in tar in a metal container about the size of a one pound coffee can. Labeled the Model 5, 100 of these "breadboard" receivers were sent to each of Kent's nationwide auto parts distributors. A somewhat similar experimental receiver had been presented to President Harding in August, 1921. This was the first radio receiver installed in the White House and it was this type of publicity which Kent used more and more during the "Roaring 20's." Until late 1923, Kent concentrated on the manufacture of individual radio parts, all of beautiful appearance and fine construction. At the same time Kent conducted a vigorous advertising campaign in consumer magazines such as The Saturday Evening Post, plus hobby magazines like Radio News (now Electronics World). To avoid becoming entangled in the complicated patent situation that existed regarding radio circuits, Kent purchased, for a moderate sum, the rights to a number of inventions of his previous patent attorney and hired a new attorney to help plan for future developments. Mass Production Quick to watch for business opportunities and to consider suggestions from his nationwide distributors, Kent announced, for the Christmas buying season of 1923, his famous Model 10 radio. This was a five-tube receiver with all parts mounted on an attractive wooden board and the wiring channeled out of sight beneath the board. The immediate demand for this receiver was tremendous and some months later, Kent modified and improved the original Model 10 and added a four-tube Model 9 receiver to his line. In late 1924 at the insistence of his distributors and in view of the competition from the growing number of makers of console-style receivers, Kent announced the Model 20 - a five-tube TRF receiver in an attractive mahogany cabinet with a gold-color nameplate. By the spring of 1925, his engineers had designed an almost identical receiver about half the physical size, which Kent personally named the "20 Compact." Kent felt that this name was a concession and an attraction to the growing number of women who had become fascinated by listening to radio broadcasts. Kent now envisioned an unlimited increase in demand for radio receivers and decided to enlarge his manufacturing facilities. He purchased a large vacant parcel of ground on Wissahickon Avenue in Germantown. The new factory was a single-story modern (then) building with good lighting for both factory and office employees. There were imposing entrances and when one passed through the reception area, practically the entire office force was visible and the heads of departments were located so that they could keep an eye on the lower echelons of office workers. This is not to say that the arrangement was designed to encourage staff heads to spy on employees; as a matter of fact, all desks were well separated and office employees were treated with more consideration than those of competitive radio manufacturers. Kent himself occupied a complete suite of offices including a dining room, kitchen and dressing room. This arrangement was used to great advantage since every day Kent invited to lunch a number of his company executives. Many of the important future plans were announced over the luncheon table with Mr. Kent speaking in a semi-New England accent with the intermittent broad "a." The Peak Years From the time of his move into the larger new factory until the depression of late 1929, the Atwater Kent business expanded by leaps and bounds. While progress was being made in the design of radio receivers, Kent continued to manufacture ignition systems for the Model T Ford, which itself remained in mass production until late 1928. The small three-dial console receiver was replaced in early 1926 by the single-dial Model 30, plus variations of the latter such as the Model 33 with a tuned antenna circuit and, later in 1926, the Model 32 with four stages of tuned r.f. In 1927 Kent turned out a battery eliminator of pleasing appearance to replace the unsightly B batteries, but it was not until RCA developed tubes in which the filaments could operate on alternating current that the true all-household electric radio receivers became a reality at a moderate price. In 1928, Atwater Kent sold nearly 1,000,000 a.c.-operated radio receivers, mostly table models, in metal cabinets with a single tuning dial. In the early 20's, while still located in the Stenton Avenue plant, Atwater Kent did not make a loudspeaker, only an attachment used to play the output of the phonograph. These attachments did not do justice to the audio quality of the receiver and in 1924 Kent had his engineers trying to develop a loudspeaker with quality equal to that of the receiver. At that time, the Timmons Company was doing a brisk business selling a large "Music Master" horn loudspeaker with a wooden bell. The Kent engineers concluded that an all-metal horn loudspeaker could give better performance. A variety of sizes of metal horn loudspeakers was made and they sold in large quantities until the magnetic cone loudspeaker with more pleasing and decorative appearance - as well as excellent reproduction-replaced horn speakers. Many different sizes and finishes of cone speakers were made in 1927-28. Advertisements showing the Atwater Kent receiver and loudspeaker appeared around the world in newspaper, magazine and catalog advertising. Competition and the Depression Competitors to Atwater Kent were not sitting on the sidelines while such enormous inroads were being made in the volume sales of radio receivers. By 1928 the Majestic Corporation had developed a high-quality dynamic speaker that was capable of reproducing a much lower range of musical notes and in 1929 Kent designed a table model for use with a separate dynamic speaker. The distinctive mark of all of these 1928-29 radio receivers was a gold-plated emblem of a full rigged sailing ship secured to the top or lid of the unit. Meanwhile, Kent used up the remainder of his magnetic speakers by manufacturing a limited quantity of "End Table" metal receivers using the 1928 chassis. At the annual sales convention in August, 1929, the Kent wholesalers had placed enormous orders in anticipation of a continuing sales boom in radio receivers. After the stock market crash however, orders were cut substantially and Kent was obliged to trim his sails. In early 1930, he had concluded that new aggressive sales techniques and advertising methods were called for. Meanwhile, his engineers were furiously designing a console-type receiver chassis that would surpass in appearance and performance that of his competitors. At the August, 1930 sales convention in Atlantic City, Kent announced and displayed the famous Model 70 and showed samples of a console cabinet which Kent was not going to manufacture. He informed his distributors at the convention that installation of the chassis into the console was to be made either by the wholesaler or retailer. The entire receiver, which was called the "Radio with the Golden Voice," was promoted in national magazine ads and billboards throughout the country. The dial, in the shape of a large illuminated arc, soon became well-known in the trade and to the general public. The price of this receiver was $275! Meantime, a local competitor announced a four-tube table model radio receiver with a founded top selling at the attractive price of $59.50. While there was probably little profit in this small receiver, it was intended as a lever for retail salesmen to talk the buyer up to the price level of a console. But, as the depression worsened and it became clear that prosperity was not around the corner, Kent's wholesalers insisted that he make a competitive model. Unfortunately, he held off doing so until the spring of 1931 with the result that receiver sales in 1930-31 were drastically reduced. Although it had become painfully evident that the boom sales of the early and mid-1920's could no longer be expected, Atwater Kent continued to turn out high-class models, both table and consoles, as well as radio phonographs. In the 30's, Kent also turned out several radios for use in automobiles and to satisfy the public's interest in shortwave listening, Kent announced various models with two, three or four bands. Later, in 1935, Kent conceived the idea of adding some home appliances to his line of products. The company designed and sold 6000 electric refrigerators. However, the venture was not as successful as had been expected and was abruptly discontinued. Big Government and Big Labor Atwater Kent treated his employees exceptionally well. Although he paid no bonuses and sold no stock in his company, he realized that public generosity could benefit the image of a multi-millionaire manufacturer. Insofar as his employees were concerned, as early as 1925 Kent had established a "Welfare Fund" and had made sizable contributions to it. When seasonal layoffs were required, this fund was used to tide over his unemployed personnel until full manufacturing production was resumed. Such an arrangement was unique in the days before Social Security and Unemployment Compensation. Possibly because Atwater Kent was such a staunch Republican and strictly a self-made millionaire, the New Deal programs of President Franklin D. Roosevelt seemed an invasion of his personal rights. The very idea of enforced Social Security and Unemployment Compensation rubbed Kent the wrong way. In the fall of 1933, union organizers began to muscle in on the radio manufacturers in the Philadelphia area. This resulted in a short strike at the Atwater Kent Company and it was settled by an agreement involving a 10% pay increase. At the time of the settlement, Kent informed the union leaders that any future attempt to interfere with his management of the business would result in his shutting down the manufacturing plant for good. From then, until June, 1936, the Atwater Kent Company continued to produce new models to conform with the trend of the times, but as sales gradually decreased and profits became marginal, it was abundantly clear that the time left for the company was growing shorter. Arthur Atwater Kent was then 62 and there was no individual, or group, he felt he could trust to maintain the good name he had built up over the years. Consequently, when union organizers approached Kent in the late spring of 1936, he bluntly informed them that, rather than grant any of their demands, he would close down the manufacturing plant and put the business up for sale. To the several thousands of employees still working, this announcement was a tremendous shock. The engineering and production departments had been planning for a vigorous fall selling season and his employees undoubtedly assumed that Kent would make a settlement. When it became clear that Kent was as good as his word, a group of about 20 of his top men pleaded with him to allow them to take over the business. To their mutual dismay, Kent refused and in June, 1936, the doors of the plant were closed for good. Those employees that had been working for Kent for 20 years were given three months salary as severance pay, but most of the others were fortunate if they could find employment either with competitive radio manufacturers or in the now well-established appliance business. Kent himself immediately headed for California, bought a palatial estate in the Bel Air section of Los Angeles and proceeded to enjoy the fruits of his many years of highly profitable enterprise. He became well acquainted with many of the celebrities of Hollywood and was noted for the extravagant parties that he gave on his estate. In the spring of 1949 he became hospitalized with a virus infection and passed away at the age of 75. At the time of the closing of the Atwater Kent manufacturing plant, the building had been put up for sale and was to include his past advertising, name, trade outlets, and good will - all for a price of $11,000,000. However, 1936 was not a propitious year for such a sale and it wasn't until 1939 that the Bendix Corporation occupied half of the plant to manufacture war materials. The other half of the plant (the 1929 addition) was soon occupied by the U.S. Signal Corp. as a training school for radio inspectors and a depot for accumulating the amateur radio equipment used by the Armed Forces in 1942-43. After the war, the entire plant building was Taken over by the Veterans Administration and is still occupied by that organization.

Posted February 17, 2023 |

|